Kidney for sale: Inside Philippines’ illegal organ trade

In the first of a two part series looking at the illegal trade in human organs in the Philippines, CNA's Pichayada Promchertchoo travelled to Manila to find out why some people are willing to give up one of their kidneys.

Human traffickers prey on vulnerable residents in poor communities as demand for kidney transplants continues to drive the organ black market in the Philippines. (Illustration: Rafa Estrada)

MANILA: Reyna comes back home looking exhausted. It has been a long day at the Philippine General Hospital. She spent most of it with two potential donors, whose kidneys could save someone’s life. They could net her some extra income, too.

Reyna is one of the ‘kidney hunters’ who roam Manila’s most impoverished communities in search of living donors. What she does is illegal. Under Philippine law, her action constitutes human trafficking for organs, a grave crime that could land her 20 years in prison and a hefty fine.

Still, the grinding poverty that defines her life is as challenging as the risk of spending decades behind bars.

READ: Kidney for sale - How organs can be bought via social media in the Philippines

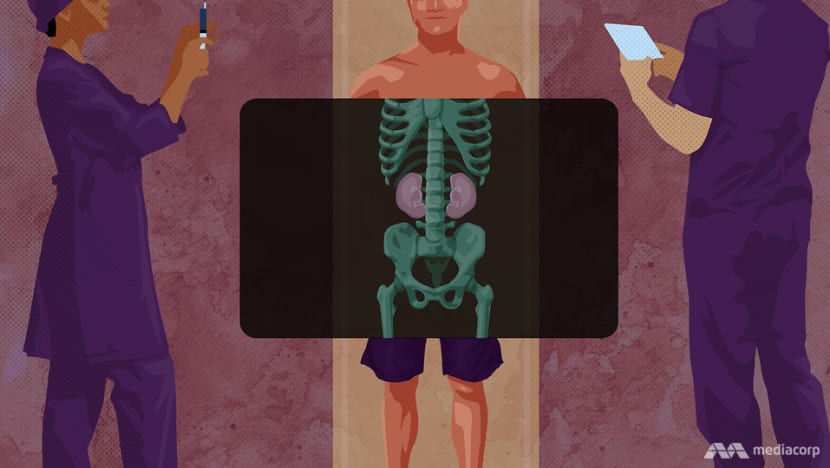

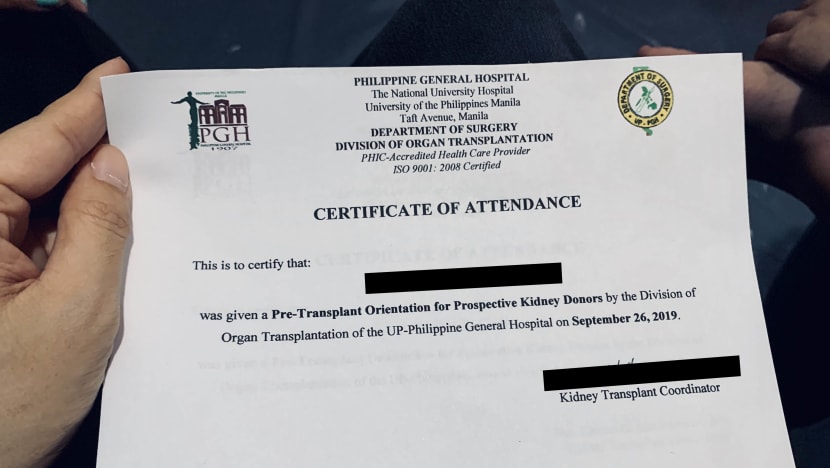

Reyna works on a commission basis. She sources potential donors and recruits them for medical exams when an order is placed. Each time she manages to bring someone for a health check, she gets 500 Philippine pesos, or about US$10. Candidates must pass a series of health tests and x-rays before any transplant can take place. The process could take a year to complete, giving her ample money making opportunities.

The reward is enticing enough to make Reyna cross into the Philippines’ illegal organ trade that has thrived underground and preyed on poor and vulnerable victims for decades.

“The government can’t really stop it. They can’t stop people who are in need, people who are just trying to make ends meet,” said Reyna inside her ramshackle home - a tiny room near a dirty gutter in one of Manila’s slums.

The latest order came from a retired civil servant with advanced kidney damage. He lives on dialysis, she said, and is willing to pay 120,000 pesos (US$2,300) for a healthy kidney from a living donor.

“It’d be unfair if I can’t help a fellow countryman who desperately needs a donor,” she said. A lanyard around her neck says she works for a government department.

The Philippines has an international reputation as one of the global hotspots for organ trafficking. In 2007, it was named as one of the organ-exporting countries in the World Health Organisation’s (WHO) report, along with India, Pakistan, China, Egypt and Colombia.

Following that, the Philippines brought in a stricter anti-human trafficking law in 2009. This contributed to declining rates of living donor transplantation, according to the WHO. The trend was also influenced by increased regulations at hospitals.

Although the Philippine government has made it harder for organ traffickers to exploit the poor and the vulnerable, it has not been able to eradicate the lucrative underground market from the country. In the ongoing attempts to put a stop to it, illegal activity is being monitored by the Inter-Agency Council Against Trafficking (IACAT) under the Department of Justice.

“As of 2019, there are about 51 cases for organ trafficking monitored by the IACAT Secretariat,” IACAT Deputy Executive Director Yvette T Coronel told CNA. One of the cases, she added, was filed in the National Capital Region and the rest in Quezon Province.

However, all the cases were only archived as none of the accused or perpetrators have been arrested, according to Coronel.

“Law enforcement agents are challenged by the fact that there is a lack of complainant for organ trafficking cases. Victims of organ trafficking also do not self-identify as such, which also makes reporting a challenge,” she said.

HOW MUCH IS YOUR KIDNEY?

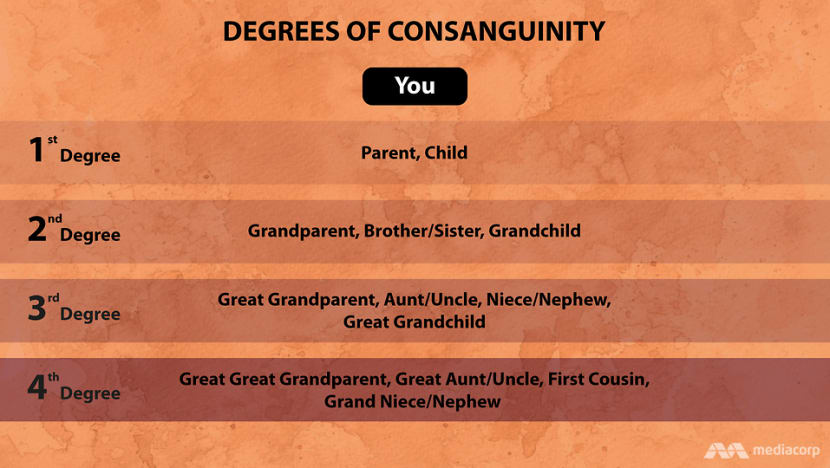

Organ donation is legal in the Philippines as long as donors and recipients are blood relatives. The law allows family members who meet specific kinship criteria to donate organs among one another. The scope includes parents and children, brothers and sisters, grandparents, and nieces and nephews.

Donation by non-relatives is also allowed - both for Filipinos and foreigners. However, the donors must prove they are emotionally related to the recipients and their act is out of altruism. A long-term boyfriend, for example, can donate his kidney to his girlfriend. Co-workers who have known each other for ten years can also qualify for a transplant.

“What we’d like to see is a long-term emotional relationship,” said Dr Benita Padilla, a kidney specialist from the National Kidney and Transplant Institute in Manila.

Without an emotional bond, any organ transplant is illegal among non-relatives. Still, such operations continue in Philippine hospitals as donation has become widely commercialised. Transactions are carried out in the clandestine organ market, which has long been an open secret in the country.

Based on online advertisements, the asking prices for a kidney can go up to 500,000 pesos (US$9,700), depending on negotiations. The usual prices are about 200,000-300,000 pesos (US$3,900-US$5,800). It is common for recipients to bear the cost of food and transport for donor candidates as well as brokers during the lengthy process of medical examination.

Organ trafficking is an organised crime in the Philippines and involves various players. It is driven by widespread poverty and a surge in numbers of patients with renal diseases. In 2016, 21,535 Filipino patients were on dialysis due to kidney failure, according to the Philippine Renal Disease Registry’s annual report. The number increased from 9,716 cases in 2010.

“We’re not so successful in preventing people from developing kidney failure. The root causes behind that are diabetes and hypertension; these incidents are increasing,” Dr Padilla said.

People who need a kidney transplant are largely those who have developed permanent kidney failure and live on dialysis. According to Dr Padilla, some 40,000 patients nationwide are on dialysis but each year, only 500 of them are likely to find their match and can afford the expensive transplant. The cost for an operation ranges from 600,000 pesos to 1 million pesos (US$11,650-19,400).

For wealthy patients, though, money is hardly a problem. Their biggest concern is rather the long waiting list for legally donated kidneys and the painful reality that they may have to spend the rest of their life on dialysis.

FROM PATIENTS TO CRIMINALS

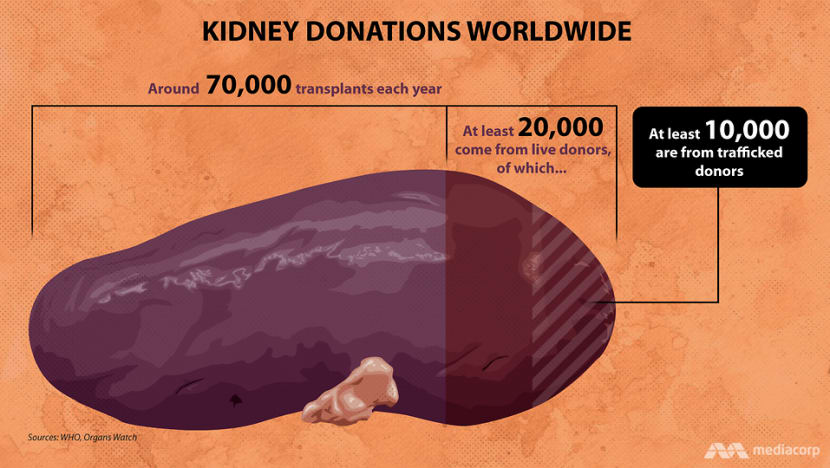

Desperation has driven many kidney patients into organ trafficking. At least 10,000 kidneys are believed to be sold around the world every year, according to Organs Watch, a US-based programme that tracks global traffic in human organs.

In the Philippines, buyers are both Filipinos and foreigners with end-stage kidney disease. They usually hire agents to recruit non-related donors, feign a relationship and falsify documents to trick law enforcement officers and medical professionals.

The agents often reach out to kidney hunters like Reyna, local Filipinos from poor communities with good social connections. Their targets are vulnerable residents with great financial needs who can be easily coerced into selling their organs.

“No rich person of sound mind would willingly donate their organs and these agents know it. That’s why they always look for possible donors in impoverished areas like this community,” Reyna said.

What drives these people to agree is their dreams. They want to be able to afford a house, a car or a tricycle so they could have a stable livelihood.

It is a situation Danilo knows only too well.

On Jul 3, 2002, the then father-of-two entered an operation room at St Luke’s Hospital in Manila. A surgeon took one of his kidneys and transplanted it to a Canadian national. The pair are non-related by blood and do not know each other.

“I wasn’t afraid because I was only thinking of my children’s well-being. I wanted to give them and my wife a house of our own. All I thought was my family’s well-being,” Danilo said. A sinister scar from that day’s surgery looks like a deep slice across his bare torso.

The surgery took six hours. Danilo sold his kidney for 115,000 pesos (US$2,200) but ended up with only 85,000 (US$1,650) after the agent had deducted his share. He used most of the money to buy a house in a Manila slum soon after being discharged. Nine months later, a fire broke out in the community and burnt down Danilo’s home.

“I was devastated to think the money I spent on the house came from selling my organ. I had no parents to turn to and was very upset. I couldn’t do anything but accept what had happened,” he said.

Seventeen years after the transplant, not much has changed for Danilo. He is still poor and lives with his in-laws in the same shantytown, sharing a tiny windowless room below theirs with his wife and five children.

The space looks more like a hole than a home - dark, stuffy and cramped. Everything about it is emblematic of hardship and struggle. Standing there, one can imagine a hand-to-mouth existence within those dilapidated walls - the kind that could easily turn a desperate person into a victim, and a criminal.

“I know it’s illegal but what matters to donors like us is that we can save another life as well as our own. The money we got from doing this is a great help, especially when we don’t have stable jobs,” he said.

Life is good when we have money, money to spend on food and toys for the kids.

‘I WOULDN’T HAVE SOLD MY KIDNEY’

Like other donors, Danilo made sacrifices for his health in saving someone’s life.

With only one kidney left, the welder gets tired easily. He used to work several days in a row but right now, his body cannot make it longer than two. He cannot skip meals either as it will cause him unbearable pain. And lifting heavy objects has become a great challenge.

If Danilo could turn back time, he said he would not have sold his kidney: “I’d rather work endlessly than being in his situation where I get tired easily.”

Many kidney donors are not aware of the side effects of the operation. According to Nancy Scheper-Hughes from Organs Watch, some underage teens in Manila’s slums were even guided by brokers to fabricate names and increase their age to match the requirement.

“They do not understand the seriousness of the surgery, the conditions under which they will be detained before and after the operation, or what they are likely to face with respect to the discomfort or immediate inability to resume their normally physically demanding jobs,” the Organs Watch director and co-founder said in her 2014 report on human trafficking.

Scheper-Hughes has spent the past decade studying the global traffic in human organs. Based on her research, most donors voluntarily enter into transactions only to realise later they have been deceived, defrauded or cheated.

The likes of Danilo are prime targets for organ brokers - poor, uneducated and vulnerable Filipinos who struggle to survive.

“Donor candidates tend to be worried because what we do is illegal,” Reyna said. “They fear it could be an entrapment operation. So I have to convince them I know the patients personally, that we’re friends and I really want to help them live. That’s how I earn their trust.”

Reyna began hunting for kidneys from living donors after her husband sold one of his. She has spent years building contacts with other brokers, buyers and potential sellers around Metro Manila. Sometimes, desperate residents approach her to offer their kidneys.

“I usually approach my neighbours to ask if they want to donate for the right price. Some of them would be scared at first. But after telling them what my husband went through and how he’s still healthy years after giving away his kidney, they feel less afraid,” she said.

‘IT’S THE ONLY CHOICE THEY HAVE’

To curb commercial organ transplants, the Philippine government instituted the National Transplant Ethics Committee in 2002. Their job is to ensure transplantation at 18 accredited facilities nationwide is performed legally, and without commercial dealing.

The committee is tasked with interviewing donor candidates and recipients to confirm their relationship. If the interviews are suspicious, they have the authority to reject the request for transplantation. But even thorough reviews do not always work.

“Is the ethics committee a 100 per cent successful? I’m not sure,” said Dr Padilla.

These people who facilitate the organ trade already know what we’re looking for. They know we’re looking for answers like ‘I’m not selling. I only want to donate my kidney out of altruism’. So now they coach potential donors to give the right answers.

Eradication efforts are being carried out by the Philippine government. According to Coronel, the Inter-Agency Council Against Trafficking and the Department of Health are in the process of reviving and reconvening the National Oversight to Control Trafficking and the National Transplant Ethics Committee.

In 2017, a stakeholder forum on the national organ donation and transplantation programme was held in support of the investigation and prosecution of organ trafficking cases, Coronel said. “The Department of Health is also working on standards for operating procedures to evaluate organ donors in the country, she added.

Authorities hope stricter regulations will put an end to the illegal organ trade and prevent traffickers from exploiting kidney patients and poor Filipinos. But in the meantime, kidney hunters like Reyna continue to prey on potential donors in vulnerable communities. Non-related candidates keep telling the right story to the ethics committee, that they are family friends of the recipients or someone close to them.

“Before a series of tests, they have to go through several interviews - with a priest, a doctor, a social worker and a psychologist. They can say they really want to help the patient. But if they decide not to donate their kidney, nobody will force them,” said Reyna.

“For some potential donors, though, it’s the only choice they have to earn money. That’s why they do it.”

NOTE: Reyna’s and Danilo’s real names have been changed to protect their identity.

This is the first of a two part series looking at the illegal trade in human organs in the Philippines. The second part, which looks at how those involved in the trade use social media to close a deal, can be found here.