20 years of syariah: From floggings to vigilante attacks, how far will Aceh go?

Has more harm than good been done in Indonesia’s most conservative province, where strict laws apply against adultery, homosexuality and gambling? And could other provinces seek to emulate Aceh’s model?

Three years ago, Aceh implemented stricter syariah laws including on adultery, homosexuality, gambling and public display of affection outside marriage.

ACEH: At 3am, there was a knock at the door. When Daud and his wife opened up, they saw a plain-clothes policeman standing there.

Just two hours earlier, Daud had placed a lottery bet via text message. Although the amount was only 10,000 rupiah (S$0.93), he was nabbed for gambling.

Under syariah law in Aceh, the 42-year-old security guard had a choice between serving a prison sentence, paying a fine in gold or being flogged in public. The sole breadwinner of his family chose the corporal punishment.

But that humiliation he endured in 2015 has left him traumatised. “To have been caned was more painful than the pain I suffered, especially when it was done in front of the public,” he told the programme Insight.

They cheered and shouted as if a football player had scored a goal. They wanted to embarrass us.

Three years ago was when Aceh implemented stricter syariah laws, including on adultery, homosexuality, gambling and public display of affection outside marriage.

Even non-Muslims can be punished. So far, at least five of them have been caned in the province for violating Islamic criminal laws.

Now, almost 20 years after Indonesia granted Aceh the right to apply syariah law, questions are being asked about how far the country’s most conservative province will go in its efforts, and whether more harm than good has been done. (Watch the Insight episode here.)

Amid rising conservatism in Indonesia as well, will this experiment with syariah law become a model for other provinces to emulate?

SAFER SOCIETY, OR LESS FREE?

To outsiders, Aceh’s syariah law may be regressive and repressive in both its concept and application. But to many Acehnese, their observance of it is but an extension of their religious duties and an integral part of an Islamic life.

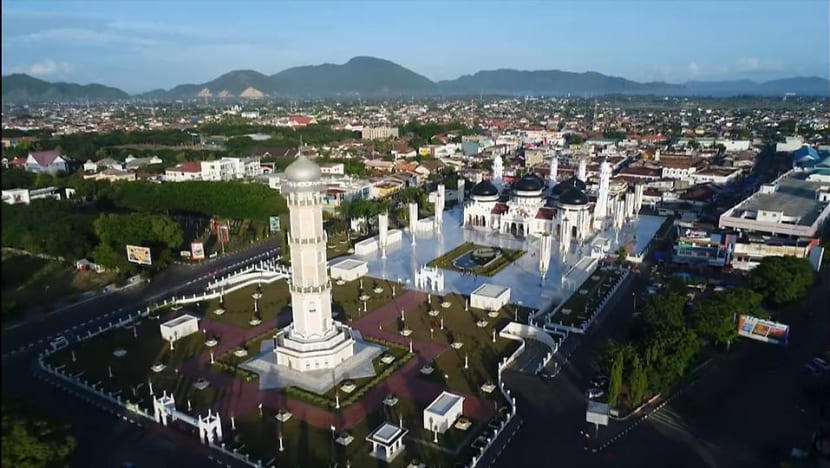

Mr Tengku Buchari Harun, an imam at Baiturrahim Mosque, the oldest mosque in the capital Banda Aceh, believes that the move in 1999 to give the province the authority to introduce syariah law has also helped to preserve public order.

“In the past, this area was full of drunk people, gamblers as well, but now, thank God, they’re all gone,” he said. “Many of them have got rid of their old habits … We’ve not seen thieves here either.”

Social activist Amron Hamdi has fonder memories, however, of growing up in a Banda Aceh where people had more freedom of choice – before the province was granted special autonomy, and with it, the formal right to enact syariah law.

As changes happened “bit by bit”, what became obvious “was the way people started to treat other people who were different from them”, said the 41-year-old.

It’s always women who get ‘criminalised’ first, starting from the way they dress.

He remembers that, in the early 2000s, a group of men started hounding women in the street who were not wearing a hijab. “There were also cases where they cut the women’s hair. It was basically ridiculous,” he added.

“We don’t want to be naked on the street or on the beach. We’re still decent human beings. We know our boundaries. But when the government starts to govern our personal lives, I don’t agree with that.”

HEAD SCARVES EVEN FOR NON-MUSLIMS

It was after the 2004 tsunami, however, that calls for a stronger implementation of syariah law were heard. Many believed that the disaster, which killed around 170,000 Acehnese, was a form of punishment.

“A great disaster came upon the people of Aceh so that they’d realise the mistakes they’d done,” said Mr Tengku Buchari.

The tragedy paved the way for an end to the three-decade conflict between the Indonesian government and the Free Aceh Movement rebel forces, with the peace accord signed in 2005.

The wider implementation of syariah law that followed has, in recent years, become even more pervasive in this province situated at the northern tip of Sumatra.

One of the groups that have felt this are the mostly Christian community of Bataks, who had been living peacefully with the Muslims – and practising their faith freely, without intimidation – for generations.

Batak native Boas Tumangger feels that syariah law has not protected their rights. “Our community, especially the Christian women, were told to wear a jilbab (a long piece of clothing) or at least a headscarf,” said the 58-year-old.

“But we had never done that before when we went to open, crowded areas such as the market. In my opinion, it has more of a negative impact because our freedom has been suppressed.”

WATCH: How lives have been affected (6:36)

Dr E M K Alidar, the head of Aceh’s syariah office, has a different view, saying that the province’s non-Muslims “don’t want to cause any trouble”, which is why they accept syariah law.

“There hasn’t been any protest from the non-Muslim community against the syariah law. They even support it and feel protected by it,” he said.

VIGILANTES AND SYARIAH POLICE

There are many cases of vigilantism, however, as well as officials who abuse their power.

In one tragic case in 2012, 16-year-old Putri Erlina was driven to suicide after the religious police arrested her for allegedly being a prostitute, and details of the arrest were published by a newspaper.

In her suicide letter, she wrote: “Father, please forgive me. I have shamed you and everybody. But I swear that I have never sold my body to anyone. That night, I just wanted to watch a keyboard performance, and then I sat up through the night with my friends.”

In 2016, a vigilante group gang-raped a young woman for alleged adultery. Now, the syariah police roam the streets every day, on the hunt for immoral activity. Unmarried couples caught in close proximity are rounded up during late-night raids.

Women are especially easy targets. Those not wearing a headscarf or who are wearing tight jeans or revealing clothing would be apprehended. Transgender women are stripped and have their heads shaved in front of laughing mobs.

READ: Rights groups decry 'shaming' of transgender people in Indonesia's Aceh province

Alcohol consumption is banned. Residents are even banned from the beaches and recreational parks at sunset.

Aceh governor Irwandi Yusuf claims, however, that the only the “mildest form” of punishments are being applied.

“There’s no cutting of hands, no stoning or even capital punishment,” he said. “What we want is for the people of Aceh to be obedient so that our social order will not be disrupted by social and attitudinal pressures.

I can say Aceh is one of the safest provinces in Indonesia. You can walk anywhere.

"A lot of coffee shops are open 24 hours a day. Women can hang around alone, walk in town and nobody will disturb them.”

Without a detailed study, however, National Commission on Human Rights chairman Ahmad Taufan Damanik is not convinced that syariah law has led to a significant reduction in crimes.

“There is no valid data on that. I think we need to compile, comprehensively, the positive aspects and also the negative aspects,” he said.

ECONOMIC IMPACT?

Even if Aceh is not as overly restrictive as it seems – men and women can move about freely in the cities, run businesses and attend university – the situation may change further if more syariah laws are introduced occasionally.

This year, the local government even mooted the idea of beheading as a method of execution for murder, which hit the international headlines.

And that is an example of the drawbacks of syariah law. While Islamic canonical law may have instilled fear in the minds of potential offenders, it has also generated a negative perception of Aceh.

Cafe owner Rahmad Hidayat feels that the overemphasis on the legalistic aspect of Islam may force investors to think twice about expanding their business in the region.

“If outsiders think positively about Aceh, they’d come. But if they think negatively, they might be afraid. A lot of people outside Aceh look at Islam as more of a kind of punishment,” he said.

“They have the impression that in Aceh, we like to flog people in public.”

READ: Indonesia's Aceh resumes public caning despite pledge to curb access

Aceh is Indonesia’s sixth poorest province, out of 34, with 16 per cent of its 5.2 million people living below the poverty line. In 2016, unemployment stood at 7.6 per cent.

But economist Rustam Effendy from the Syiah Kuala University blames Aceh’s lack of investments and poor economic situation on the conservative way the economy is run, rather than on syariah law.

“It’s moving at its usual slow pace based on a classical economy. There’s no intervention to transform it into a modern economy,” he said.

“Aceh might have good potential. It’s rich in resources … We have good farms. We have excellent mines. The sea is vast. But why is no one coming in? They might be looking at different issues, such as legal issues and certainty in doing business.”

Dr Arskal Salim from the State Islamic University of Syarif Hidayatullah agrees. “It’s a matter of management because we can see other provinces that are still in poor conditions despite the fact that they don’t have Islamic law,” he said.

CHURCHES UNDER SIEGE

The economy aside, the growing conservatism is making matters worse for Aceh as it turns into religious intolerance, with churches under threat of being attacked or demolished.

In 2015, a group of young men took to the streets of Singkil, a rural district 650 kilometres from Banda Aceh, and demanded the demolition of all churches in the district.

After their demand was ignored, they burnt the Christian Church of Gunung Meriah to the ground.

“The police simply stood by while the attack happened. They did nothing. They only said, ‘don’t, don’t, don’t,’” recounted Mr Tumangger, one of Singkil’s prominent church leaders at the time.

Instead of delivering justice, the authorities then demolished five other churches within the district. Their argument was that the churches were built without permits, even though some of them had existed before Indonesia’s independence.

Mr Ahmad believes that government inaction has emboldened the extremists. “That’s why attacks from groups against Christians have increased year by year,” said the human rights commissioner.

INDONESIA’S SECULAR PRINCIPLES AT RISK?

Nationally, politicians have also been bowing to demands from hardline groups in exchange for votes.

A 2016 study published in the journal Third World Quarterly found that at least 442 Syariah-based ordinances, including curfews on women, had been passed throughout Indonesia since 1999.

Some provinces are now keen to implement syariah law the way Aceh has, noted Dr Salim. “But the issue here is the constitutional position of those provinces,” he said.

“Do they have a similar right to claim what Aceh has been offered? I guess they have no right to claim as such.”

Still, it worries Mr Ahmad that this will be an issue of national security or national integrity.

And only time will tell if Aceh’s attempt to return to the golden age of Islam would set the stage for the erosion of Indonesia’s secular principles.

In Aceh, however, there seems to be no turning back. To the majority of its people, syariah law is sacred and a marker of their identity.

“There’s only one syariah province in Indonesia, and that’s the reason why we prefer living here than elsewhere,” said Mr Tengku Buchari.

But for Mr Amron, who has been living in Jakarta for 17 years now, as long as syariah rule takes priority over the province’s economic well-being, he does not plan to return.

“I’ll visit my family there. I love Aceh, as I said before. But to live there, to have a career? I don’t think it’s a good place for me. Maybe for other people, but not for me at the moment,” he said.

Watch the episode here. The programme Insight is telecast on Thursdays at 8pm.