Setting my son, the trapped chatterbox, free

Severe cerebral palsy made it tough for Sayfullah to express everything in his heart. This is story of how a mother’s love and assistive technology helped him find his voice.

SINGAPORE: Like any teenager, Muhammed Sayfullah, 14, is extremely particular about his music selection. He enjoys the latest tunes - bring on the Justins (Bieber and Timberlake). And don’t forget Bruno Mars.

“He will cry if he doesn’t like the song playing in his school van,” his mother Siti Fadillah, 39, tells us as we wait for her son to arrive.

Said van soon rolls up to the driveway shelter, and Madam Fadillah gets up to ensure her son’s wheelchair is safely locked in. As the doors slide open, she looks up and chirps: “Sayfullah! ...Oh no.”

Her son’s face is crumpled like a fallen pastry at the sight of mummy, and he breaks into loud, uncontrollable sobs.

As though she has done it a thousand times before, Mdm Fadillah smiles calmly as her son wails, and carries his slight frame out of the van into the wheelchair. Once he is properly strapped in, her quest to discover whatever trigged the meltdown begins.

When he was a month old, Sayfullah was diagnosed with quadriplegic cerebral palsy - the most severe form of cerebral palsy (CP), which is characterised by the loss of motor skills caused by brain damage. In Sayfullah’s case, it has also made his speech unintelligible to most people.

His mother, however, is a master decoder.

It turns out that the song selections playing in the van that day had been satisfactory – the subject of Sayfullah’s angst was his lunch at school: White beehoon, which he dislikes.

“He likes yellow noodles. Yellow is his favourite colour,” says Mdm Fadillah, as her son continues to make his grievance loudly, if inchoately, known. But her gentle smile never wavers.

“MAYBE HE NEEDS MORE OF ME”

If you had asked Mdm Fadillah nine years ago to give up her job at an aviation company to become a full-time caregiver, she might not have readily said “yes”.

“It really wasn’t an easy decision to make because I was so used to working life. And it was a job I really enjoyed,” she said.

For two years, her mind drifted between being a working mum and being a caregiver to her son. Her heart eventually settled on the latter when she realised Sayfullah was hungry to learn more than what he was being taught in school.

“My son was able to identify colours, shapes and numbers. He wanted more. That is where it hit me: Am I dedicated to him? Maybe he needs more of me.

So I said to Sayfullah, ‘Mummy is not going to work anymore and we are not going to have so many privileges. But I am going to spend time with you. Mummy is going to be your teacher’.

With the free time that she now had, she got down to work. She researched cerebral palsy and special needs education. She started using flashcards to teach him phonics, addition and subtraction.

But the results were not instantaneous. It took five years before Sayfullah was able to recognise words.

Now, Mdm Fadillah sets five-year plans for her son.

“I have friends who tell me, ‘You must be crazy to set five-year plans for a special needs child. Don’t push him too hard. They can’t do much. Let them enjoy life.’

I said, yes. They should enjoy life. But when we are no longer here to assist them, what are they going to do? What can they do if you do not impart skills to them now?

“As parents, we need to do more. We can’t just sit still.”

FINDING SAYFULLAH’S VOICE

When Mdm Fadillah first found out that her son was diagnosed with CP, she was devastated, sad and above all, lost.

“Doctors said he is unable to walk. He is unable to do normal activity or live like a normal person. As time went by, I also realised that there’s no cure for CP,” she said.

“I was heartbroken when people said Sayfullah is unable to do things.”

Disheartened, she asked his speech therapist out of desperation: “Can you tell me, what is he able to do? We need him not only to read, but to talk.”

In 2012, when Apple’s third-generation iPad took the world by storm with its new features (such as the Retina display), Mdm Fadillah saw a golden opportunity for her son. She thought, was there a way to use the iPad as a communication device for her son?

Yes, said the speech therapist. Mother and son were introduced to assistive technology (AT), which is any device or product that helps persons with special needs overcome barriers.

At age 9, Sayfullah laid hands on his first iPad at Enabling Village, a community hub set up by SG Enable. He learned how to type with one finger as a means of communication.

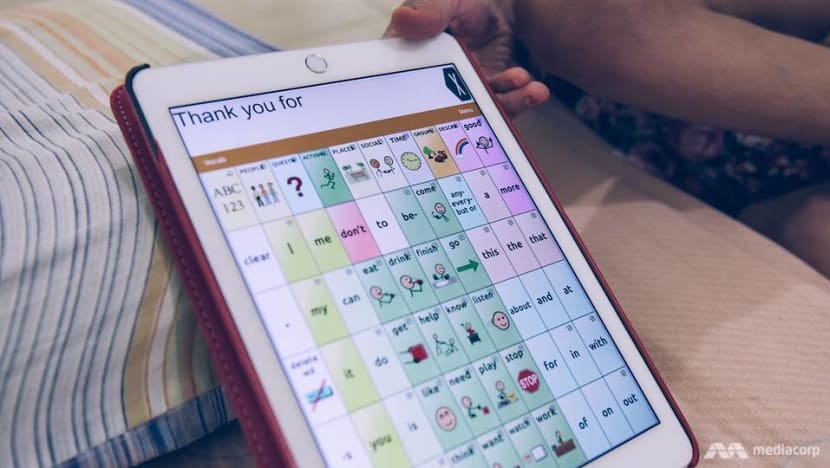

A year later, he started using an application called Touch Chat, which enables him to spell and form sentences by combining different symbols. After he constructs a sentence, an automated voice reads out the message.

And that was how Sayfullah found his voice. He turned out to be really quite the chatterbox.

WATCH: Their emotional journey (9:40)

FEELING ALONE

On Christmas in 2016, Sayfullah attended a party without his iPad. He set a challenge for himself: To prove that he could still communicate with others using his speech.

The atmosphere was loud and jolly. People talked over each other in excitement as games were in session. Everyone seemed to be having a good time.

Days after the party, an IT specialist who was working with Sayfullah asked if he enjoyed himself. To everyone’s surprise, he broke down.

Sniffling through tears, he typed on his iPad: “I felt alone.”

The importance of a communicative device became crystal-clear to Mdm Fadillah. “It really helps him to articulate his feelings. As a mum, I can understand (his speech) because I’ve spent years with him. But what if he’s going to talk to strangers?”

That does not mean that his speech is rendered useless.

“A lot of people think that if a person has an augmentative communication device, they’ll stop talking,” said Ms Sarah Yong, the clinical manager of SPD’s Assistive Technology Team.

“That’s not true. We never want to stop a person from using their speech, but we do realise that it is quite limiting.

“As a person, you want to say everything that’s in your head. You don’t want to settle for second best.”

And in Sayfullah's case, she said: "You could see from his body language that he wanted to tell you a lot of things."

MAKING TECHNOLOGY A PRIORITY

Seeing how AT is truly life-changing, Mdm Fadillah hopes it can be fully incorporated into the special needs school system. Unlike mainstream schools, special needs education tends to focus more on life skills, she said.

“More can be done definitely, in terms of using technology in the classrooms - not only at home, or for a single individual but in group settings. It should always start at school, since the children are there almost every day,” she added.

In the third Enabling Masterplan - which are five-year national plans to support people with disabilities and their caregivers - one of the key strategic directions is to make technology a priority to improve the quality of life of persons with disabilities.

To achieve that, it is recommended that “both mainstream and Special Education (SPED) schools strengthen their use of AT to enhance learning outcomes”.

Ms Yong said that the AT team from SPD has been conducting training with “special needs schools, allied educators and teachers from mainstream schools”.

“We also have a loan library of 500 types of AT. Schools, teachers and professionals can come to loan these devices and use it for a certain time with their clients or in their schools.”

If the technology is found to be useful, individuals may then purchase it with assistance from the Ministry of Social and Family Development's Assistive Technology Fund. The fund provides up to S$40,000 of subsidies over their lifetime to pay for AT devices.

Mdm Fadillah has been able to tap on the fund for an iPad Pro and new wheelchair for Sayfullah. Next, she is setting her eyes on mounting a bluetooth speaker onto the wheelchair so that the automated voice on Touch Chat can be heard even in crowded places.

Said Ms Yong:

A lot of times, we look at what can’t the person do. But we need to look at what they can do. Can we use technology, can we think outside the box?

“AT is about empowerment.”

SAYFULLAH’S A-TEAM

Mdm Fadillah is almost always out of breath when you meet her. How are you, you ask her, and her standard reply is: “Busy. Very busy.”

It is no surprise. She is taking care of her three children on her own – Sayfullah is her eldest, Shaista is 12 and Shaheed is 4. On top of that, her ageing parents, who are also living with them in their two-room flat, are not in good physical condition.

Her 67-year-old mother is recovering from a recent back operation. Her dad, 65, stopped working as a part-time cleaner because of knee problems.

Most days find Mdm Fadillah shuttling from home to school or the hospital for her parents and Sayfullah’s appointments. But, she is not alone.

With Sayfullah in a wheelchair, a taxi is the most convenient way for the family to move around. This initially posed a great challenge.

“We tried to flag taxis along the roadside. Mostly, we were just turned away,” she lamented. “Some stop, but drivers never assist to carry the wheelchair in even though it’s very heavy.”

What really upset her was drivers chiding her not to scratch the boot or make dents with the wheelchair. “Why would I, or anyone, want to do such a thing?”

But things got better. With the help of social workers from KK Women’s and Children’s Hospital, Mdm Fadillah’s family became a beneficiary of the KKH Health Fund, a member of SingHealth Fund. When they go for hospital appointments, they can book a London cab - which is wheelchair-accessible - for free.

Mr Cephas Teo, affectionately known as Uncle Cephas, has been ferrying the family for seven years.

“The children love him. We were given the option of requesting for different drivers each time but they only want Uncle Cephas,” said Mdm Fadillah.

She also gives credit to the hospital social workers who have worked closely with her family over the years. All hospital bills are subsidised with her Medical Fee Assistance Card, and she receives financial aid monthly from Club Rainbow, a non-profit organisation.

While the amount is “just enough” for the family of six, Mdm Fadillah is grateful.

“I have a lot. I am blessed to have all these good people. They told me that if I need help for anything they can always come together to find a way.”

“STOP CALLING HIM DISABLED”

When Shaista was in kindergarten, her brother became a popular talking point for her classmates.

To Mdm Fadillah indeed, the possibilities for her son are endless. With assistive technology, she hopes that not only will his confidence level in communicating grow, but that he will also grow up to be independent.

“Sayfullah has been learning how to use a joystick to navigate his laptop and iPad. We are getting him to control the speed of the cursor and, who knows, maybe he’ll able to do simple video editing or create Powerpoints in the future,” she said.

Even as she charts the next five years for her son, Mdm Fadillah knows she needs to be realistic.

“At night before I sleep, I am constantly thinking of what else can I do for him, and you realise you are only human. You can’t do so many things.

“You just have to remain positive even if things don’t go according to your plans. We shall see what comes in the future.”

Lowering her face to her son who is sitting on her lap, she says will all a mother’s assuring confidence: “You can do it, my love.”

For more inspiring stories of those who've overcome the odds, check out CNA Insider.