Last Day at Work: The SCDF officer who cared for people and helped save lives

In the series where Channel NewsAsia profiles individuals leaving the workforce after long careers, Aqil Haziq Mahmud speaks to an SCDF senior commander who valued relationships above everything else.

Senior Assistant Commissioner Christopher Tan outside the SCDF headquarters. (Photo: Gaya Chandramohan)

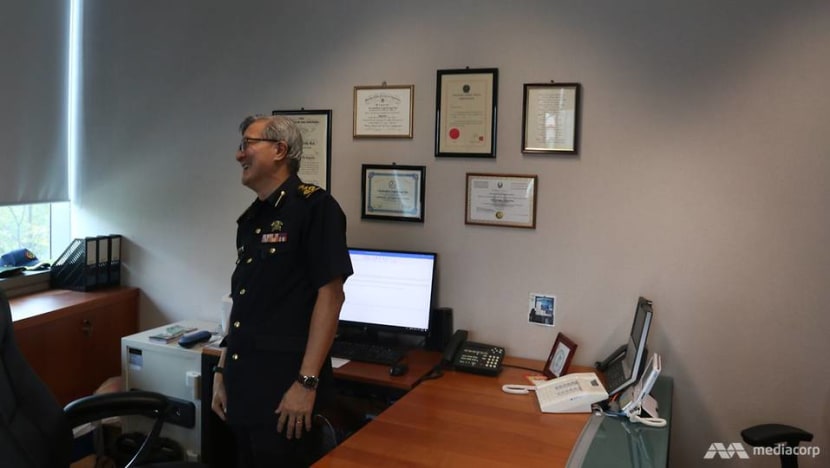

SINGAPORE: On his last day of work, Senior Assistant Commissioner (SAC) Christopher Tan’s spacious office was unusually messy.

The 60-year-old pulled out dozens of old photos, smiling and reminiscing about his 35 years in the Singapore Civil Defence Force (SCDF). After all, it was his one and only career.

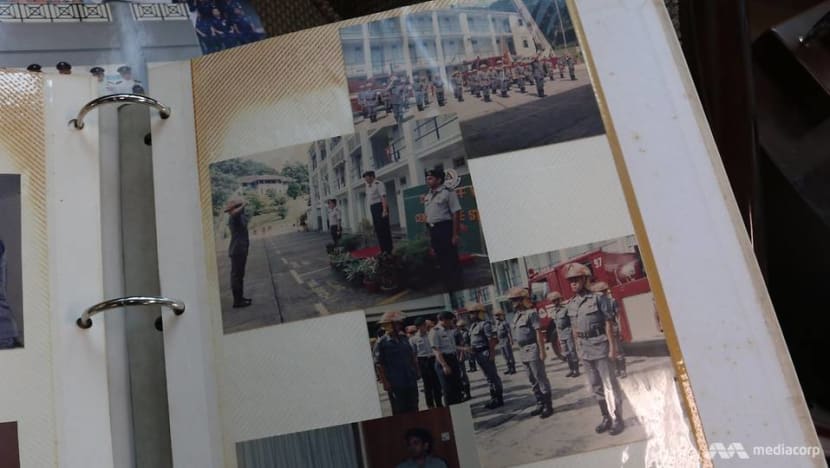

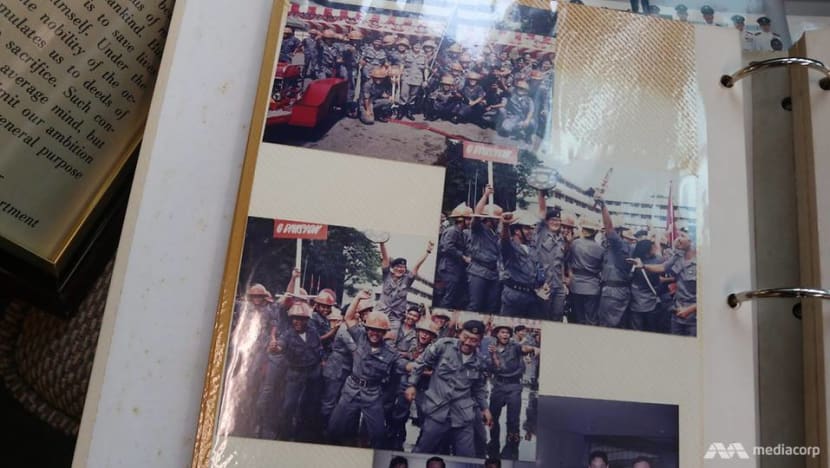

Some of the photos are arranged in neat albums, others stacked in haphazard piles. In one photo he is beaming, carried on the shoulders of cheering colleagues. In another he is stern, getting briefed near a badly burnt shophouse.

SAC Tan has led battles against fires of all kinds: The kind that razed houses and killed people, and the kind that engulfed industrial buildings and sent steel drums flying.

He’s also witnessed the devastating aftermath of a major earthquake, commanding a team toiling through the night to sieve through rubble for signs of life.

As a senior officer, his primary duty at the frontline was command and control. But he's also had some quieter moments.

SAC Tan's final post was director of the fire safety and shelter department, where he ensured new and existing building designs complied with the Fire Code, which reduces risks in the event of a fire. It was an unspectacular, yet equally important role.

Still, the early years of his career epitomised the kind of all-action job that comes with a whole lot of risk and honour, the kind that some kids grow up dreaming about.

EARLY DAYS

The man himself, however, did not have grand ambitions of working with the SCDF.

In 1986, after graduating from the National University of Singapore with a degree in building, SAC Tan looked for a job relevant to his education. He gravitated toward a career in the public service in the hope of better pay and prospects.

But at the time, the building and construction industry wasn’t exactly booming. “Nobody was hiring,” he told Channel NewsAsia from his office at the SCDF headquarters in Ubi, lamenting the lack of construction projects back then.

There was one job, though, which wasn’t ideal but still seemed to fit: A position in the building plans branch of the fire safety bureau, a unit in the then-named Singapore Fire Service. His friend from university, who was already in the force, recommended him to apply.

So Tan signed on with the SCDF as an officer. And as they say, the rest is history. Still, he didn’t think he would spend the next three decades of his life in the same organisation.

“Honestly, I just needed a job,” SAC Tan admitted. “I just wanted to give myself a chance, to just experience it and see how it goes.”

But soon he found himself growing fond of his new job, where he vetted building plans against the Fire Code. This includes having fire extinguishers and sprinklers where needed, and ensuring sufficient and convenient escape routes.

SAC Tan was applying his textbook knowledge to real-life scenarios. “It excited me that I was doing something real,” he said. “Whatever we advised the engineers or architects, it’s going to affect the safety of the building.”

COMMANDING A FIRE STATION

But the realities of his job were only going to become clearer. In 1990, SAC Tan became officer commanding of the iconic Central Fire Station on Hill Street, where he took charge of about 100 personnel and 15 emergency vehicles.

From behind a desk, SAC Tan was thrust onto the front line.

“What crossed my mind was now I was going to lead a team to fight a fire,” he said. “Am I able to do it well? Because they are going to look at you for direction. And they are people with many, many years of experience.

“Will they respect and accept me as their superior?”

SAC Tan overcame this by always asking his senior subordinates for advice during operations. He would involve them in discussions, and they would pick up on things he missed.

“People like to be respected and treated well,” he added. “When you consult them, they think you value their views and experience. That’s important.”

SAC Tan also engaged his rank-and-file personnel about things like welfare and living conditions at the station, eager to see how they could be improved.

“I don’t just build relationships with my bosses, but my men as well,” he said. “Because they will be the ones who will support you and look after your back. In a fire, if there’s a risk, they will be the ones pulling you out.”

When it came to fighting fires, it was often a matter of life and death. Because of the station’s location, SAC Tan attended multiple incidents in the Rochor area, which then had a lot of fire-susceptible shophouses. He also witnessed a lot of deaths.

“It boils down to poor fire safety education and design,” SAC Tan said, noting that the shophouses were made of materials like timber, and had grilled windows with only one staircase escape route.

One particular incident stuck in his memory.

In the dead of night, he responded to yet another shophouse fire near Ophir Road. The flames were raging as his team battled to put it out quickly. “We must not assume that there’s no one trapped,” he said. “The faster we put it out, the faster we can go inside and do a search and rescue operation.”

It was too late. On the second floor, they found at least seven bodies. SAC Tan believes they were not able to escape because the window was obstructed, a situation made worse by overcrowding.

For SAC Tan, his multiple encounters with death had taken a psychological toll, although he got used to it after a while.

“I do feel a bit affected by it,” he said. “Some are charred beyond recognition. But I know for one that if we get emotionally attached, it will affect our actions and decisions.

“Importantly, I tell my men: You must treat each case you are responding to as though you are doing it for your loved ones.”

TACKLING AN EARTHQUAKE

As the years went by, SAC Tan moved up the ranks, eventually becoming commander of the 4th division in 1998 to oversee four fire stations in northwest Singapore.

He responded to even bigger fires, like one which tore through an industrial warehouse in Jurong after reactive chemicals were improperly stored. The fire was so huge it made steel barrels explode, turning them into dangerous projectiles.

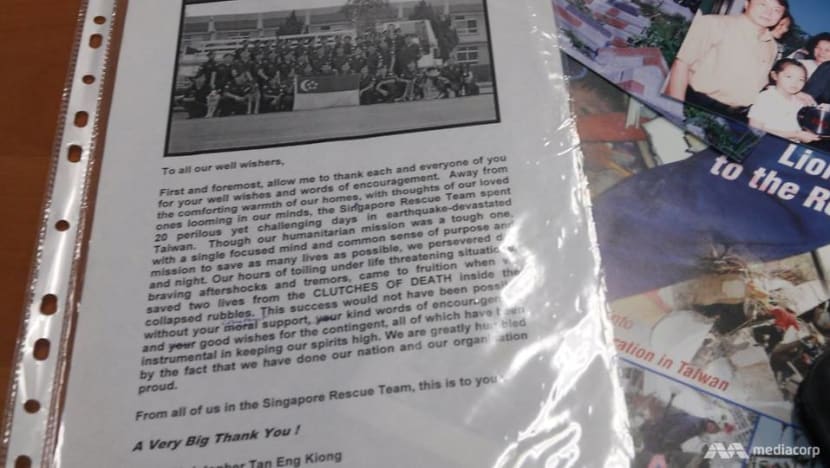

But perhaps his toughest assignment yet came on Sep 21, 1999, when a 7.6-magnitude earthquake ravaged Taichung County in central Taiwan.

At 9am, the SCDF’s Operation Lionheart contingent, which provides urban search and rescue and humanitarian relief assistance overseas, was put on alert.

SAC Tan was the division commander on standby for the operation. “There was a very short reaction time,” he said. “You need to do a lot of things when you are activated.”

The men had to be called back, while standby equipment like drills and life detectors had to be taken out and tested. At the same time, SAC Tan was trying to get more information on the disaster, details of which were “quite sketchy”.

“All these raced through my mind as I tried to make sense of what is going to happen there and how I am going to manage it,” he added.

Despite the whirlwind of his own thoughts, SAC Tan had to prepare his men. As soon as they were activated, he reminded them of what lay ahead.

“We have a mission and failure is not an option,” he stressed. “We are going there to make a difference and save lives.

“I told them we are going there together, we are coming back together. No one is going to come back in a box. So, I want everyone to work as a team and take care of each other’s safety.”

By 5pm, 44 SCDF personnel – including two operationally-ready national servicemen and one full-time national serviceman doctor – together with four rescue dogs departed for Taiwan in a military plane.

SAVING LIVES

It was past midnight at the disaster zone, but it was easy for SAC Tan to see the collapsed structures, as he recalled one nine-storey building half submerged in the ground.

“We were the first overseas rescue team there, so there was no time for anything,” he said. “Just straight into ground zero and the action starts.”

The rescue dogs scoured a search area spanning a few blocks, narrowing it down for rescuers to detect movement or sound under the rubble.

Without local building plans, residents were asked to sketch rough diagrams of where their kitchens and bedrooms were – likely places where survivors would be trapped – on cardboard boxes. SAC Tan said it would be wasteful for rescuers to spend hours inadvertently drilling into a toilet.

The team ended up working for 72 hours straight with minimal rest, braving aftershocks while looking out for each other. “We saw a lot of people in hysteria and crying,” SAC Tan said. “You just cannot stop. They are depending on you to hopefully find their loved ones.

“We didn’t feel the tiredness until we finally pulled out.”

Their efforts paid off. The team had saved two lives, including an eight-year-old boy who had been trapped under the rubble for 30 hours. The mission had lasted an exhausting 22 days, one of the longest operations in the SCDF’s history.

“Even if it’s just two lives, every life saved is monumental to us,” SAC Tan added. “It was a success.”

At the disaster site, locals thanked the team for their efforts. One lady even gave SAC Tan a Bible in appreciation of his work.

“These are some of the gestures that keep you going,” he stated. “This thing is very much in us: When we turn out for any rescue operation, no matter how daunting it is, we have to give our best.”

LIVING AND WORKING ABROAD

SAC Tan thought he had passed the most difficult test of his career, but in late 2005 he encountered something that would turn out to be even more challenging.

The Qatari government had asked Singapore for help in setting up a fire safety regulatory framework, so SAC Tan was asked to go there to do the job – for two years.

To keep the family together, his wife and two school-going daughters decided to come along, meaning they had to take no-pay leave and a break from local education.

Once there, SAC Tan had to overcome many difficulties, including the sweltering 45-degree Celsius summers, lack of a support group and an unfamiliar culture.

At work, he said there was a different way of approaching tasks, with some apparently unnecessary delays and meetings that were less productive than he was used to. “My concern was really the deliverables,” he added. “Because (after) two years they will ask what have you done? Nothing.”

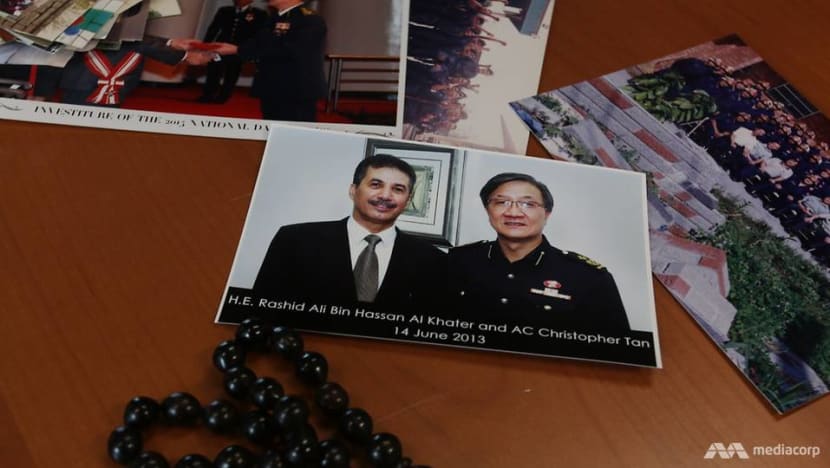

But he stayed patient and built relationships with the Qataris, delivering what he needed to while earning their respect. He is good friends with the ambassador till now, and the country still sends its officers to Singapore for training.

On the social front, he made life easier for Singaporeans working in Qatar by starting a community for them to meet up and share tips. For his daughters, he found a piano teacher just so they could continue their lessons, even flying one of them out to Bahrain for a ballet exam.

When it was time to go home, his daughters asked if they really needed to. They had made good friends at the international school and asked if he could extend the contract. His family had gained a lot and grown stronger, but “it’s time to go back”, he said.

SAC Tan said his time in Qatar made him realise just how much he took things in Singapore for granted. “It was a life-learning experience,” he added. “On reflection, it was not a bad decision.”

IMPROVING TRAINING OF RECRUITS

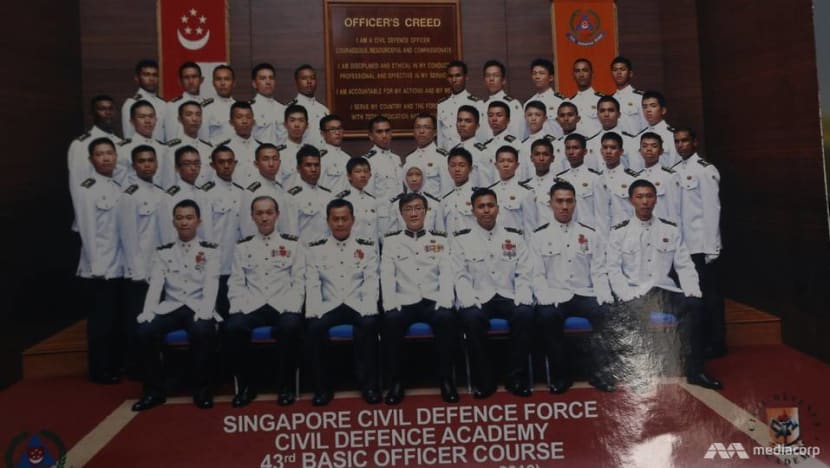

After returning home in 2008, SAC Tan became director of the Civil Defence Academy, which trains new recruits and other personnel in areas like firefighting and disaster management.

He called it one of his most memorable postings, especially as he constantly looked to ensure everyone was well-trained for their jobs.

“Training, capacity building is something that I enjoyed doing,” he said, adding that he liked interacting with the people there. “How can we do it better is always something in my mind.”

SAC Tan, a firm believer in using technology to do things better, took his job seriously.

He replaced physical flip charts with Internet-connected electronic screens so training material could be conveniently updated. He helped introduce a 3D, augmented reality training simulator which helps trainees improve their road accident rescue skills.

Beyond that, he made it a point to walk the ground day and night, eat in the same cookhouse as the trainees, and observe their training. This also kept instructors on their feet.

“They thought the director is in the office all the time, in an air-con room not knowing what is happening,” he said. “But for me, no. The important part is showing the men and instructors you are serious about training.”

COMING FULL CIRCLE

In 2013, SAC Tan left the academy to become director of the fire safety and shelter department, his final appointment before retiring.

After starting out in fire safety, his career had come full circle. Now he still dealt with building plans and the Fire Code, but was helped by a great deal of technology.

For instance, his team used fire modelling software to test and improve the parameters of the code, so they were not too restrictive. When developers required a waiver for complex buildings like the Sports Hub and Esplanade, he studied their alternative proposals and made a decision.

It was a fine balancing act that sometimes involved dealing with profit-driven industry players who didn't like overregulation.

“I think the misconception that some people have of us is that we are rigid and inflexible in the way we regulate fire safety,” SAC Tan said.

On the contrary, he said it was important to engage stakeholders for their expertise and experience, and discuss alternative solutions where possible.

“We can’t just force it down their throat and force them to comply with it,” he added. “We always take a calibrated approach where we assess any situation or project.

“You try to strike a balance, but at times we’ve got to take a hard decision. Between profitability and life safety, of course safety takes precedence. So, we have to bite the bullet.”

This job might not be as exciting as fighting fires or saving lives, but SAC Tan said it was just as crucial. “I always believe fire safety is the upstream process, you must do it well,” he said. “If a building is well-designed, chances of fire occurrences are lower.”

BEING A PEOPLE PERSON

On his last day of work, SAC Tan still looked excited about his job. He said he’s never had a dull moment nor any major regrets in his career.

If he had to do something differently, it would be spending more time with his colleagues and engaging them on a deeper level.

“I think we are so caught up in the day-to-day work, chasing reports and all these things, that we don’t spend time building that relationship,” he said. “The deeper conversations, understanding people better.”

SAC Tan is a people person. His smile is warm, and throughout the interview he was always offering food and drinks. “Don’t you want to taste the best prata here?” he asked.

He liked sharing his memorabilia with people too.

Besides the old photos he pulled out, there was that Chinese Bible from Taiwan, some prayer beads gifted by the Qataris, and a plaque from President Halimah Yacob thanking him for his service.

Ultimately, the most rewarding part of his job was not the tokens he had collected.

“When we are able to do it well and see the happy faces of people, the assurance that we have brought to them – putting out the fire, stopping the spread and so on,” he said. “That’s the biggest satisfaction that I can get.”