commentary Commentary

Commentary: After Alaska, age of selective engagement in US-China relations begins

With tensions spilling over in public, the US and China’s frosty diplomatic meeting is a sign of things to come, says Bert Hofman.

Secretary of State Antony Blinken, accompanied by National Security Adviser Jake Sullivan, right, talks to the media after a closed-door morning session of US-China talks in Anchorage, Alaska on Friday, Mar 19, 2021. (Photo: AP/Frederic J Brown/Pool)

SINGAPORE: The run-up to the US-China meeting already foreshadowed the challenges that the actual bilateral discussions in Anchorage would encounter.

In fact, the two sides could not agree on how to call it. For the US, it was a meeting to communicate positions to the other side.

For China, it was a “high-level strategic dialogue”, a continuation from where the countries had left off before Trump entered the White House.

Tensions spilled over in public, in the first session, when under the eye of cameras from all over the world, the US and China had what in diplomatic terms can only be described as frosty.

US Secretary of State Antony Blinken opened with criticising China for actions that “threaten the rule based order that maintains global stability.”

State Council member Yang Yiechi replied: “We believe that it is important for the United States to change its own image and to stop advancing its own democracy in the rest of the world.”

READ: Commentary: Joe Biden’s quietly revolutionary first 100 days

Yang spoke for 15 minutes, well in excess of the agreed 2 minutes, sparking an unprogrammed, on-camera reply by Blinken. Suffice to say that this was an unusual start for a diplomatic meeting between the two most powerful countries in the world.

THE ROUTE TO ANCHORAGE

The Chinese side came into this meeting full of confidence. The country had managed the COVID-19 crisis well, delivered growth, and had kept its commitment to eliminate absolute poverty.

Internationally, it has just scored major political victories in the form of agreements on the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) with Asia-Pacific countries, and the Comprehensive Agreement on Investment with the European Union.

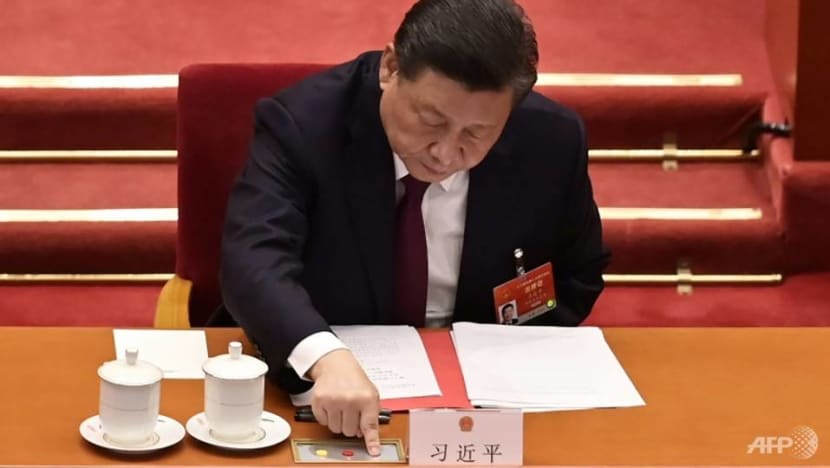

China’s views are that this is their time and that amid “changes not seen in a century”, it has a “strategic opportunity” to deliver on its China Dream of the country’s rejuvenation. “The East is Rising, the West is Declining”, as Xi Jinping summarises China’s views.

China’s 14th Five-Year Plan - the first for the new era for socialism with Chinese characteristics as President Xi laid out in 2017 - aims to propel the country to a modern socialist state by 2035.

The new economic strategy underpinning the plan, the so-called "dual circulation”, aims for greater self-reliance in demand, supply and technology.

This is good insurance against the type of measures that the Trump administration imposed upon China, even if it may mean somewhat slower growth.

The plan doubles down on investment in technology, and in particular on basic science, to become self-sufficient in “choke-hold” technologies such as integrated circuits.

In addition, for the first time, “security” was included in the table of main indicators of the plan, with mandatory targets for food and energy security.

Nevertheless, China prefers continued engagement with the US on equal terms. As Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi said in a media interview earlier this year, the Chinese “reject decoupling and uphold cooperation".

China’s characterisation of the Anchorage meeting as a “high-level strategic dialogue” is a clear reference to the Strategic and Economic Dialogue between the countries, which was initiated under presidents Barack Obama and Hu Jintao in 2009 – and was an upgrade of the former Senior Dialogue and Strategic Economic Dialogue started under the George W Bush administration.

This dialogue continued under Xi Jinping, but was abandoned under Donald Trump.

READ: Commentary: Expectations for reset in US-China relations must be managed

READ: Commentary: First high-level US-China meetings seem destined to flounder

The US came to Anchorage from a very different position. After four years of the Trump presidency, it is only starting to “Build Back Better” as President Joe Biden has characterised his grand strategy.

His focus is on investing in the domestic strengths of the United States, in its R&D, in its infrastructure and in its people. The US$1.9 trillion stimulus package that had recently passed Congress is a first step, but the route is a long one.

The administration has made clear that it will take its time to develop a China strategy, but the Interim National Security Strategic Guidelines already offers a down payment: China is an adversary, a competitor and a partner, depending on the topic at hand.

The US strategy’s aim is to allow it “to prevail in strategic competition with China or any other nation.”

The Biden administration has also made clear its commitment to the status quo on Taiwan, and has sent freedom of navigation patrols through the South China Sea.

Secretary Blinken and National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan visited Japan and South Korea first, before heading to Anchorage.

Moreover, just before the meeting, the US put several deputy chairpersons of the National People’s Congress, China’s Parliament, on a sanctions list because of their role in passing the National Security Law for Hong Kong.

ANCHORAGE IS NOT SUNNYLAND

The frank exchange in Anchorage was not necessarily a bad thing, though. First, that the meeting happened was important by itself.

Second, that the two parties were willing to express their positions and grievances, even in public, was refreshing, and perhaps healthy for a longer-term relationship, in which there surely will be more difficult issues to discuss.

In addition, a meeting beats no meeting, given the downside risks of the latter.

At the same time, the gathering did not result in an agreement of any sort, nor did it set a possible agenda for future engagement, let alone a date for a future Biden-Xi summit.

Anchorage made it clear that there is no return to Sunnyland, the venue of the Obama-Xi meeting in 2013. That meeting, among others, laid the basis of the Paris Climate Change Accord of 2015.

The Sunnyland spirits did not last, though, and by the time Trump took office, the US-China relationship had already soured on multiple fronts, including on industrial policy, cyber espionage, and intellectual property rights.

READ: Commentary: US must confront China’s assertive, expansionist Asia strategy

Trump, despite bragging about his good relationship with Xi, ran down the bilateral relationship, especially in the final year of his administration when poor management of COVID-19 started to threaten his re-election.

At the same time, Trump did China a big geopolitical favour by backing out of the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), and by alienating America’s traditional partners as former Australian Prime Minister Kevin Rudd pointed out in his recent Goh Keng Swee Lecture at the East Asian Institute.

READ: Commentary: Is it too late for the US to join the CPTPP?

Anchorage saw the emergence of a new baseline in relations: One with more select engagement, and diminished expectations as to where China-US engagement may lead.

WHERE TO GO FROM HERE?

The US is likely to focus on its domestic agenda and further rebuilding of ties with its traditional allies. President Biden already reconfirmed his strong commitment to European allies and NATO at the Munich Security Conference last month.

He has also signalled his intend to work closely with the Quad, the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue, in the Indo-Pacific. The first summit of the leaders of the Quad members - the US, Japan, India and Australia - on Mar 12 signalled this could become an important tool for the Biden administration’s foreign policy.

France and the United Kingdom are already seeking closer engagement with the group, and are set to join maritime manoeuvres together with Quad countries.

Moreover, according to the summit’s joint statement, the Quad is expanding its engagement into areas such as health, technology and trade, and seeks to “uphold peace and prosperity and strengthen democratic resilience, based on universal values".

READ: Commentary: Is China too big to tame? No easy answers to Quad’s central challenge

The big question is whether ASEAN countries are interested in the Quad. As observers have noted, the closing statement of the Quad leaders’ summit mentions ASEAN centrality - which is a subtle invitation of sorts to ASEAN countries to join in.

Some may well do so in select areas of concern, such as technology. For now though, the Quad falls well short of offering the economic attraction that a China has for the rest of Asia.

China has a busy domestic agenda of its own in the coming two years. This July is the 100th anniversary of the founding of the Chinese Communist Party, and next year, China is hosting the winter Olympics.

In 2022, the Communist Party will also convene its 20th Party Congress, a once-in-every five-year event. It is of particular importance this time because it is likely to reaffirm Xi’s ambitions for another term as the Party’s general secretary as well as China’s President.

These domestic events will absorb most of Beijing’s political attention.

READ: Commentary: Is China using Myanmar coup to ramp up influence in Southeast Asia?

Having both countries focus on a domestic agenda may not be a bad thing, as long as lower-level exchanges continue.

This is particularly in areas such as the military where the risk of incidents is increasing in light of growing activities in the region from both sides.

It will also allow time to develop a more in-depth substantive agenda for any future high-level engagement. Meanwhile, big global issues such as climate change can still be addressed, but multilaterally rather than in the context of the China-US relationship.

Hopefully the next high-level meeting will come with lunch included.

SIGN UP: For CNA’s Commentary weekly newsletter to explore issues beyond the headlines

Bert Hofman is Professor of Practice and Director of the East Asian Institute, National University of Singapore.