CNA Explains: How does Article 156 in the Constitution 'protect' marriage?

A stock photo of a bride and groom holding hands. (Photo: iStock)

SINGAPORE: Minister for Family and Social Affairs Zulkifli Masagos on Thursday (Oct 20) tabled a Bill to amend the Singapore Constitution to protect the definition of marriage from legal challenges.

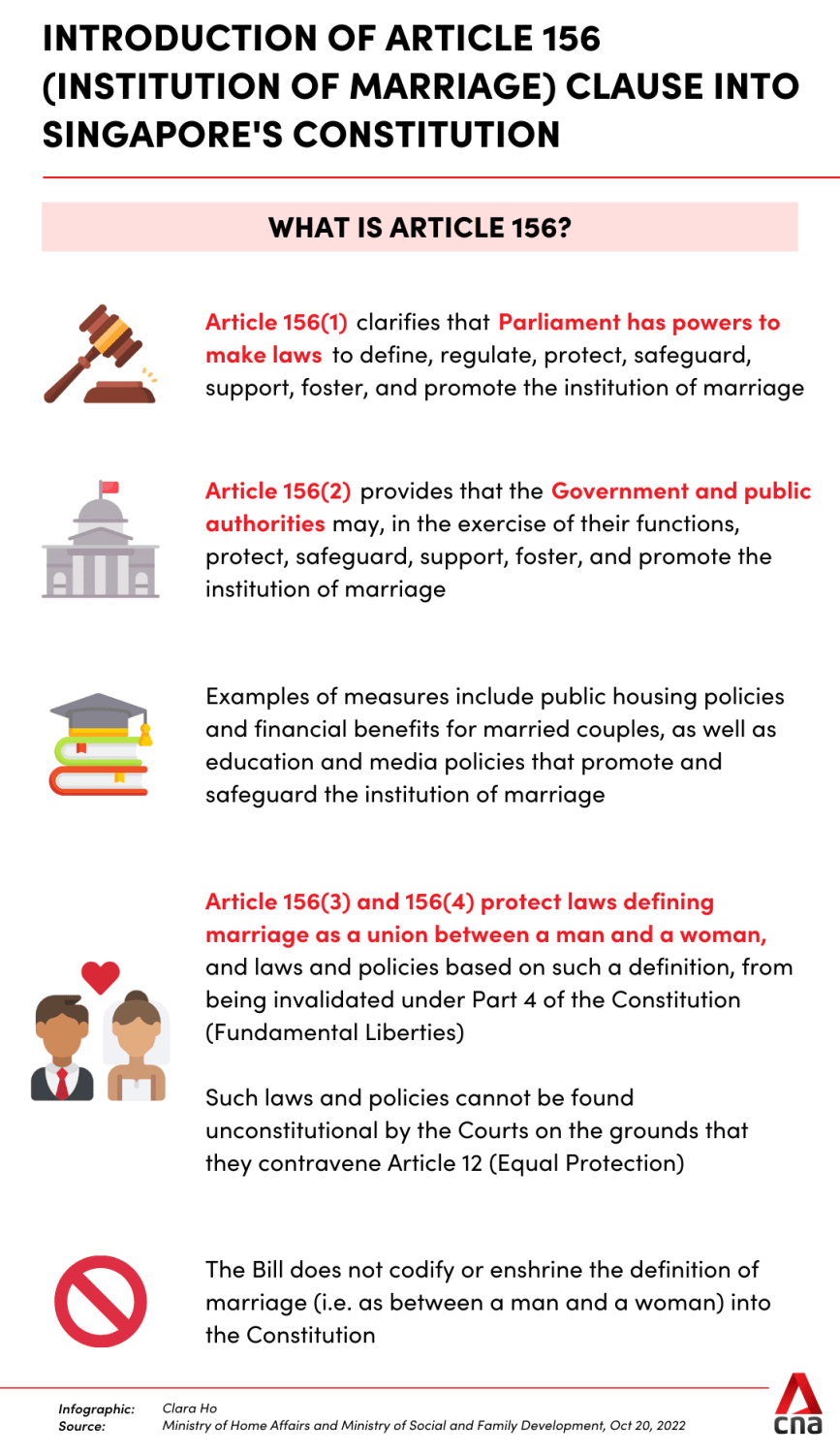

The Constitution of the Republic of Singapore (Amendment No. 3) Bill seeks to introduce Article 156 which states, in short, that Parliament will have the power to define, regulate, protect and promote the institution of marriage. It has four subsections.

It was tabled in Parliament along with another Bill to repeal Section 377A - a law that criminalises sex between men.

What does Article 156 hope to achieve and why is it being proposed? CNA speaks to lawyers and experts to interpret the legal terms.

Full text of Article 156

Institution of Marriage

156. (1) The Legislature may, by law, define, regulate, protect, safeguard, support, foster and promote the institution of marriage.

(2) Subject to any written law, the Government and any public authority may, in the exercise of their executive authority, protect, safeguard, support, foster and promote the institution of marriage.

(3) Nothing in Part 4 invalidates a law enacted before, on or after the date of commencement of the Constitution of the Republic of Singapore (Amendment No. 3) Act 2022 by reason that the law -

defines marriage as a union between a man and a woman; or

is based on such a definition of marriage

(4) Nothing in Part 4 invalidates an exercise of executive authority before, on or after the date of commencement of the Constitution of the Republic of Singapore (Amendment No. 3) Act 2022 by reason that the exercise is based on a definition of marriage as a union between a man and a woman.”

HOW TO INTERPRET ARTICLE 156?

The key clause in part (1) of the Article is that Parliament has the power to define the institution of marriage.

What it hopes to achieve is that Parliament will have sole power to define what marriage is and such definition by Parliament will not be subject to legal challenge, said Mr Suang Wijaya, lawyer at Eugene Thuraisingam LLP.

The Article would make such challenges an “uphill task”, said the constitutional law practitioner.

Subsection 2 states that the executive, that is Government, would have the power to act to “further any purpose as to the current definition of marriage”, said Mr Wijaya. The word “define” is dropped from the text, but it seeks to cover all other functions with the terms “protect, safeguard, support, foster and promote”.

The proposed Articles 156(3) and (4) refer to Part 4 of the Constitution, which contains constitutional rights provisions, such as the right to equality, said Assistant Professor of Law Benjamin Joshua Ong, from the Yong Pung How School of Law at the Singapore Management University (SMU).

“For example, Article 156(3) appears to prevent someone from arguing that the definition of marriage in the law violates the constitutional right to equality because it does not provide for same-sex marriage,” said Asst Prof Ong. Subsection 156(4) does the same for the executive or Government and its policies and measures.

SMU Associate Professor of Law Eugene Tan said the intention is to “significantly reduce the likelihood of constitutional challenges on laws and government policies that are premised on marriage being that between a man and a woman”.

“The provision makes it plain and clear that what is a marriage is for Parliament to decide,” said Assoc Prof Tan.

He added: “The constitutional amendment Bill does not codify the definition of marriage in the Constitution. In so doing, it does not unnecessarily bind future governments and generations on the definition of marriage.”

WHY NOT “ENSHRINE” IT IN THE CONSTITUTION?

If defined in the Constitution, any future amendment to the definition of marriage would require a supermajority, or votes from two-thirds of the elected Members of Parliament and Non-Constituency MPs.

Asst Prof Ong said that by not doing so Parliament can change, by ordinary legislation, the definition of marriage that is currently set out in Singapore laws. This is now the case, and the proposed Article 156 would not change that.

Parliament can also, by ordinary legislation, create a system of civil unions, including same-sex civil unions. The proposed Article would not change that.

These can be amended or enacted with a simple majority of sitting MPs.

WHAT DOES IT PROTECT?

Article 156 does not enshrine the definition of marriage in the Constitution, but marriage is defined in other legislation.

Section 12 (1) in the Women’s Charter says that a marriage that is not between a man and a women is void.

It reads: “A marriage solemnised in Singapore or elsewhere between persons who, at the date of the marriage, are not respectively male and female is void.”

The Interpretation Act defines a “monogamous marriage” as “a voluntary union of one man and one woman to the exclusion of all others”.

There are various policies that are based on these definitions of marriage including public housing policies, financial benefits for married couples, adoption and media and education policies.

WHY NOW?

At the National Day Rally, Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong gave two main reasons for the repeal of Section 377A and the proposed amendment to the Constitution to protect the traditional definition of marriage.

He said that society is now more accepting of homosexuality and that most accept that it should not be a crime for consenting men to have sex in private.

The other reason was there was a real risk that Section 377A could be overturned in a future court challenge, on the grounds that it breaches the equal protection provision in the Constitution.

This refers to Article 12(1): All persons are equal before the law and entitled to the equal protection of the law.

Article 12(2) adds “there shall be no discrimination against citizens of Singapore on the ground only of religion, race, descent or place of birth” in any law or in other matters.

Professor Leslie Chew, Dean of the School of Law at the Singapore University of Social Sciences said that without the new Article 156, the way marriage is now defined may suffer challenges, the way Section 377A was.

“Hence, based on the Government’s sensing of the views of the majority of Singaporeans, Government in turn, takes the position that it ought to strengthen the legal status of the definition of marriage so that a constitutional challenge such as that which has been repeatedly mounted against 377A over a decade or so, will not occur,” said Prof Chew.

He added: “Given the divisive nature of the issue, I believe Government is trying to balance the competing claims of the status quo and the evolving nature of modern life so as to ensure harmony within our society.”

COULD ARTICLE 156 BE CHALLENGED?

It is an undecided question in Singapore whether it is possible for the court to strike down constitutional provisions that are seen to be contrary to fundamental parts of the Constitution, said Mr Wijaya.

Asst Prof Ong said that one could use the “basic structure doctrine” to argue that that certain parts of the Constitution, such as the rights provisions in Part 4, are so “basic” that the Constitution cannot be amended to reduce the scope of those rights, which Article 156 arguably purports to do.

“Our courts have not yet stated conclusively whether or not this theory applies in Singapore,” he said.

WHAT HAPPENS NOW?

The two Bills - one to repeal Section 377A and the other to amend the Constitution - were tabled for their first reading in Parliament on Oct 20.

There will be a second and third readings of the Bills at a subsequent sitting on Nov 28.

The Bills will be debated together but voted on separately. The Penal Code (Amendment) Bill can be passed with a simple majority.

The Constitution amendment Bill needs the assent of two-thirds of the 92 elected MPs and two Non-Constituency MPs to pass. This means a total of 63 votes.

The ruling People’s Action Party has 83 MPs and the party whip will not be lifted for the vote.

All Bills need to be examined by the Presidential Council for Minority rights to make sure that it does not discriminate against any race or religion, and the President’s assent before being gazetted as law.