The interpreters using their bilingual proficiency to give others 'a voice in the courtroom'

Access to justice shouldn’t depend on being able to understand legal proceedings in English. But interpretation is not about regurgitating what speakers say in another language, a common misconception debunked by interpreters from Singapore’s three courts.

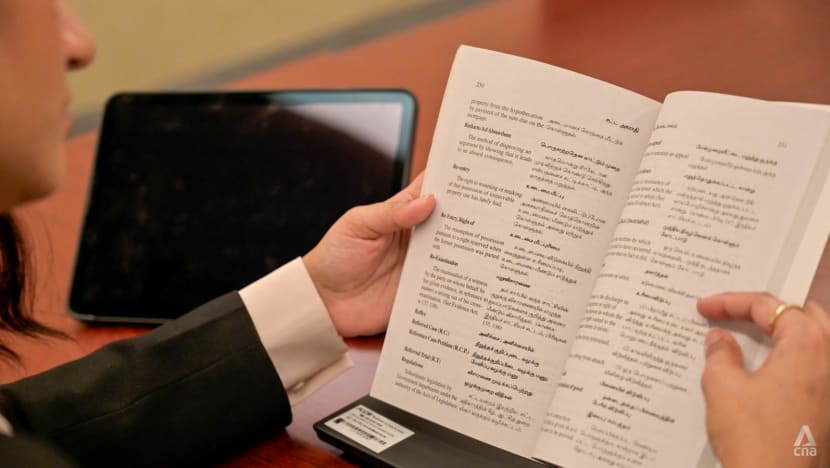

Court interpreters (from left) Tay Meng How, Khairunnisa Nabilah Zainal Abidin and Christina Amrita Arul at the Supreme Court library. (Photo: CNA/Eugene Goh)

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

SINGAPORE: Every parent's nightmare was once a mother’s reality.

The woman had not only learnt her young daughter was a victim of sexual assault. She also had to testify in court against the alleged perpetrator, someone she trusted.

But all court proceedings in Singapore are conducted in English – a language she wasn’t comfortable with.

The case that happened a while ago was assigned to court interpreter Christina Amrita Arul, who still vividly recalls the mother being “very uneasy when testifying”.

“I could tell there was a lot of guilt and shame that she was feeling, and she was really hesitant when answering. At some point, she would even resort to gestures; she just couldn’t bring herself to say certain things," she said.

"That makes it very difficult when you need to interpret."

So the 31-year-old Tamil interpreter “changed her tone and style of interpretation” to put the woman at ease.

“We can’t really control some of the terms and details (from a case) that may come up in court, because they can be very explicit, can be crude, can be really awkward. But I tried my best to handle the situation with tact and care, and I could see it made a difference for her,” she said.

Court interpreters don’t just interpret for accused persons, she added. Many who need interpretation services are witnesses and victims too.

And it is a court interpreter’s duty to help any of these individuals understand their rights and the processes, as well as feel comfortable in court so they remain coherent – while keeping one's own emotions at bay.

Emotional detachment didn’t always come naturally for Ms Christina, who has been with the State Courts for over five years, as much as she knows objectivity is “the best way to help”.

“I would feel particularly strongly about certain cases, and carry it with me for quite a while. It took some time to learn to detach myself,” she said.

Yet, her struggle is one of several that are fairly common among court interpreters, said those who opened up to CNA about the ins and outs of their lesser-known profession.

"OUR JOB IS TO BE THEIR MOUTHPIECE"

Having served at the Supreme Court for over two years, Malay interpreter Khairunnisa Nabilah Zainal Abidin has handled her fair share of sexual offence cases.

These often require the 25-year-old to interpret the statement of facts – a document containing material facts about the offence including how it was allegedly committed – and can be “very horrifying to read”, especially in cases involving family members.

“It’s very easy to feel swayed by your emotions and look at the accused person in a certain way, but we have to remember to interpret ethically. Our core duty is to interpret for whoever needs our service,” said Ms Nabilah.

“When we interpret for an accused person, it’s important to remember that they are innocent until proven guilty. And our job is to be their mouthpiece, as they may not understand or speak English very well.”

Moreover, translation and interpretation are vastly different skills, she clarified, having often been mistaken for a translator. Translation focuses on written content, giving someone more time with a document, while interpretation is “pretty much on the spot”.

“Your brain is constantly working. So mental fatigue is quite common, especially if we interpret for witnesses for hours at a time.”

At the Family Justice Courts, Mr Tay Meng How manages his emotional boundaries by prioritising helping people get access to the legal assistance they need, regardless of their English proficiency.

Those who require interpretation services in these courts tend to carry “powerful emotions, because they’re dealing with personal and sensitive matters”, said the 34-year-old who interprets in Mandarin and Cantonese.

“I remember a case where the court user filed for maintenance for wife and child applications. She was very visibly emotional and was having a lot of difficulty communicating with the judge,” he shared.

"So I took cues from her body language and the way she was responding to the judge; I took the initiative to calm her down, to explain the court’s question and to provide her interpretation in simple Mandarin to aid her understanding.

“After that, she expressed tears of joy and gratitude, because she felt she was able to have a voice in the courtroom … She was able to fully participate in court proceedings and also (had) access to justice.”

People think court interpreters merely "regurgitate and parrot" what the speaker has said in another language, but that is far from the truth, he said.

“You have to guide (the individual) through their personal, sensitive family matters, and help to manage their potentially intense emotions with great care as well.”

The rapport between court user and interpreter is not always a given. Mr Tay has been questioned about his Cantonese proficiency, but he usually reassures the individual that he is trained to interpret in the dialect and asks for a chance to assist them.

Other times, court users may get overly comfortable with interpreters and pose the “frequently asked question”: What are their chances of winning the case?

Interpreters are neutral parties and cannot provide such advice, said Mr Tay, adding that he would also remind the individual that each case is unique and the decision lies with the judge.

MASTERING SLANG, SYNTAX NUANCES

As such, court interpretation isn't just about bilingual or multilingual ability.

Mr Tay, who used to work in communications, pointed out that knowing Singapore Mandarin is “not sufficient” these days for his role.

While most initial requests for Chinese interpretation services once came from middle-aged Singaporeans, these court users now include Malaysians, mainland Chinese and Vietnamese – all of whom have varying accents and use terms unique to their country or region.

He noted that Vietnamese spouses tend to have a different pronunciation of Mandarin words and pepper their speech with other dialects, such as Hokkien. Even though he officially interprets in Mandarin and Cantonese, he would nonetheless need a basic understanding of various dialects “to ensure every part (of their speech) is captured”.

A competent interpreter must possess “a certain level of language proficiency that goes beyond conversational fluency”, added Mr Tay, who has been in the job for a year.

“This means to be able to master the chosen language – including listening, speaking, reading and writing, as well as, most importantly, to develop an in-depth cultural and contextual understanding of both languages.”

He illustrated that Singaporeans tend to say "shi qian" to mean 10,000, even though the standard term is "yi wan".

The difference could be due to Singaporeans being primarily educated in English, hence a direct translation of 10,000 to Mandarin would be shi (“ten”) qian (“thousand”).

And "zhou ri" refers to Mondays to Fridays in Singapore Mandarin, while mainland Chinese nationals use the word to describe just Sundays, Mr Tay added.

Mainland Chinese court users also adopt certain online slang in daily conversation that Singaporeans don’t, he said. Being prepared for these terms is crucial as they’re “not something written in the affidavits”.

For instance, the phrase "tang qiang", which “literally means lying on the gun, because they feel that they have been unjustly held responsible for a mistake or wrongdoing”.

The Malay language is similarly “rich in idiomatic expressions” that might not have an English equivalent, Ms Nabilah said. She admitted once having “very textbook knowledge” of idioms, as those her age don’t use these in daily conversations.

“But when I became a court interpreter and had the opportunity to interact with people from all ages, I could observe the use of such proverbs and figurative language, and it helped me better understand the meanings and their exact equivalents in English.”

Ms Nabilah highlighted that the idiom “kais pagi makan pagi, kais petang makan petang” might not make sense if translated word for word.

“But the English equivalent is ‘to live from hand to mouth’. Older generations like to use this kind of language, so you have to know what they mean,” she explained.

The Tamil language is no stranger to slang either, added Ms Christina, pointing to "kadalai podrathu", a phrase commonly found in informal settings like social media.

It means “flirting with someone”, although one “would not be able to understand that just based on the words”.

Then there are syntax differences to note. While English follows the subject-verb-object order, Tamil uses subject-object-verb, said Ms Christina.

Unless she’s doing simultaneous interpretation, in which case she anticipates what’s coming, she waits for the entire sentence to be said before “working backwards” to interpret.

In addition, Tamil is a “highly diglossic language”, which means the language has two different forms, she pointed out.

“There’s a very formal, literary form that is used in official settings (like in) official documents or in schools, (where) we’re taught a certain kind of Tamil. But in everyday speech, Tamil is very different; there’s a colloquial Tamil used.

"Sometimes you need to find the balance between those two forms of Tamil (when interpreting).”

PROFICIENCY IN LANGUAGE – AND LEGALESE

With excellent emotional intelligence and a keen understanding of cultural nuances needed for the job, on top of language mastery, court interpreters must therefore pass a professional certification exam to work in the courts.

The “rigorous” exam comprises three main components that require “sharp thinking”, Ms Christina said.

The first involves roleplay. Participants are not given a heads-up and are expected to prepare themselves for any scenario.

The second involves conference interpretation, where a recorded speech is played with pauses between every few sentences. Then participants are tested on their ability to interpret with “split-second accuracy, making sure that no meaning is lost and we capture all information”, she said.

The third involves sight translation. Participants are given a “very short amount of time” to read through a document before interpreting “on the spot”.

But perhaps the more intimidating challenge was eventually having to grasp legalese, said those who spoke to CNA. None of them had a legal background.

Even someone fluent in English would feel daunted in court, never mind a non-English speaker who would likely find the jargon “even more anxiety-inducing”, said Ms Christina, who used to work in publishing.

When she first joined the State Courts, she struggled with “simple things”.

“For example, a counsel could just say (their client is) taking a certain course of action, and you're just supposed to know that means the accused person is going to plead guilty,” she noted.

“Or the judge would ask: ‘What do you intend to do?’ And in that situation, you have to know actually he’s asking: ‘Are you going to plead guilty, are you claiming trial, or are you going to engage counsel?’”

Looking up published judgements to practise their interpretation skills, shadowing senior interpreters and attending “mock court sessions” are among the activities that help new interpreters get up to speed.

Mr Tay underwent a six-month induction programme, including “competency training” to familiarise himself with common English and Chinese terms used in court proceedings at the Family Justice Courts.

“(We might simulate) a mock court session on a case, perhaps about maintenance applications … So our seniors will roleplay as the parties (and) come up with certain dialogues that are quite representative or reflective of the situation in court. We practise accordingly to gain our confidence,” he shared.

The courts also provide in-house programmes and specialised external training to help interpreters hone their techniques, including note-taking. But a bulk of the learning happens on the job and is often self-motivated.

Most of their time is spent doing background research for the cases they are assigned, because interpreting is more multifaceted than “just going to court and rendering service”, said Ms Nabilah.

She familiarises herself with case-specific information – names, numbers and places are important – so she can pick them up instantly when she is required to interpret simultaneously.

Court interpreters also look out for any concepts or vocabulary unique to the case that they should know, she added. For example, sexual offence or murder cases usually contain “a lot of medical terms and body parts used to describe the injuries”.

“As professional interpreters, we must possess a good range of vocabulary, good knowledge of legal provisions and concepts, idiomatic expressions, cultural nuances, as well as a good mastery of grammar and syntax,” she reiterated.

Ultimately, however, the best interpreters are those who interpret “in a way that sounds very natural”, noted Ms Nabilah.

She learnt this pertinent skill during her sharing sessions with senior interpreters.

“Sometimes, they will say I sound like I am reading from a text because I’m very formal. Just because you’re a good interpreter doesn’t mean that you have to sound so classy and elegant. You should also be able to make sure that your parties understand what you’re saying,” she said.

“There is no point if you know all the technical words, but you’re not able to break it down for the person listening to you.”