Trying fishing for the first time at Bedok Jetty – and learning how to do it sustainably

Marine Stewards, a non-profit marine conservation group, is organising workshops about sustainable fishing. CNA’s rookie fisherman Aqil Haziq Mahmud went along to see what lessons he could learn, including how to catch anything at all.

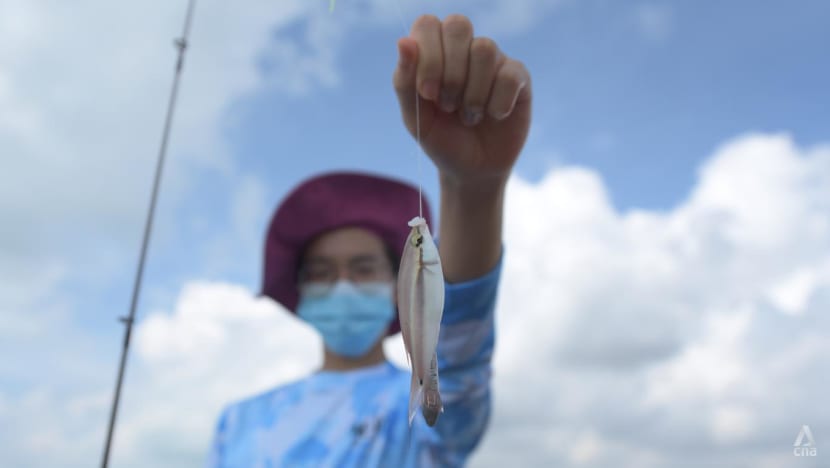

CNA journalist Aqil Haziq Mahmud fishing with SGFishingRigz angler Wayne Peh at Bedok Jetty. (Photo: Try Sutrisno Foo)

SINGAPORE: While I have never tried recreational fishing before, it hadn't occurred to me that the hobby could have an impact on sustainability.

How could the actions of one angler on Bedok Jetty compare to the kind of overfishing done commercially? Besides, is it not the point of fishing to bring something home for dinner? After all, why else would you spend hours under the hot sun waiting for that elusive nibble?

These were the thoughts I grappled with on a sunny Tuesday morning (Nov 23), when I arrived at the jetty in East Coast Park for a sustainable fishing workshop organised by the Marine Stewards, a non-profit marine conservation group.

The group had teamed up with local fishing shop SG Fishing Rigz, whose anglers provided the gear and expertise to catch and release fish. The start-up is also promoting sustainable fishing through the use of environmentally-friendly sinkers and circle hooks that boost survival rates.

But I was keen to find out if I could even catch anything – I have heard of anglers who spend hours by the water only to go home empty-handed – and beyond that, why I should do it sustainably.

The first clue was a giant signboard right at the entrance of the jetty. No, not the one that talked about how the jetty was used exclusively by the Ministry of Defence before it was opened to the public.

It was another blue signboard, designed by the Marine Stewards, that showed different species of fish that could be caught at the jetty, how big they get when mature, and whether they should be released back into the sea. The general guideline: Juveniles should be released so they can grow and repopulate fish stocks.

I walked down the jetty and was greeted by people wearing caps and the blue Marine Stewards jersey. I asked programme director Andrea Leong why sustainable fishing was important.

"In countries like US and Australia, they (have) got really healthy marine life because they have really strict fisheries management laws," she said.

"But in Singapore, there aren't these laws. It's really about the community guidelines that we came up with. The idea is that for this sport to be sustainable in the long term, we need to be fishing sustainably, so that we don't deplete all the fish."

Not depleting fish is crucial when seen in the bigger picture. Each person in Singapore consumes an average of 22kg of seafood a year, above the global average of around 20kg.

In 2020, Singapore imported 134,000 tonnes of seafood worth S$760 million, mostly from countries in the region such as Indonesia and Malaysia.

Given the finite number of fish in oceans and Singapore’s food security goals, this rate of consumption and imports could be a cause for concern, argued Professor William Chen, who studies foods science at Nanyang Technological University, in a CNA commentary.

So if one angler chooses to release 500g of fish every two weeks, this means 1,000 anglers would release one ton of fish per month, or 12 tons a year. These fish get to grow big and spawn, creating a multiplier effect, the Marine Stewards said previously.

WAITING GAME

With the theory part done, it was time to get down and dirty. I was handed over to 18-year-old Wayne Peh, who does business development for SG Fishing Rigz. This was my first time fishing, I told my guide excitedly.

The thing about catching fish is that it is not just about casting a line into the sea.

So when Wayne asked if I would like to try attaching shrimp to the two hooks on the line fishing line, this wiped the smile off my face. I always got lazy when it came to peeling the shell off prawns during meals. But because I really wanted to fish, I did it anyway.

Wayne instructed me to tear up the shrimp into smaller pieces of meat before hooking it on. The hooks were sharp, and I felt one almost going underneath my nail. "Careful," Wayne warned.

The next step was to cast. I was looking forward to pulling the rod back, throwing it forward and hearing the whip of the line flinging far into the sea. But since I was using a beginner rod that was shorter, Wayne told me I merely needed to hold it over the water before letting the line fall in. I would be lying if I said I was not disappointed.

The way to let the line roll out is to lift the bail arm, a kind of lever, on the reel. The sinker should go all the way to the seabed, Wayne said. When this happened, the reel stopped spinning and I felt a little thud in the rod. Wayne unwound some more line before closing the bail arm.

Now came the most infamous part of fishing: Waiting.

While Wayne said it could take hours to catch a single large fish, he assured that smaller fish could be caught in minutes. And since my rod was designed for smaller fish, he was hopeful that I would succeed.

Wayne showed me how to hold the rod properly, with my master hand on the rod handle and my other hand controlling the reel handle. I have always thought that the master hand was used for the reel, considering how vigorous the action could get. Maybe I just watch too much television.

Still, what happens in real life paints a more grim picture.

Wayne recalled how one of his colleagues at his fish shop visited Bedok Jetty during the lockdown, when fishing there had stopped for a long time, and discovered an abundance of fish in the water. "It was one cast, one catch," Wayne said.

But because there were so many fish, the anglers who were there simply left the smaller ones they caught under the stone benches to die, when they could easily be released into the water. This was when the shop decided it wanted to spread the message of sustainable fishing.

Related:

On Tuesday, the fish were not exactly out in force.

Five minutes went by, nothing. I should feel nibbles in my "sensitive" rod, Wayne said, adding that this was the sign for me to jerk the rod upwards before spinning the reel handle. I was not sure if I was feeling nibbles or just the current swaying my bait.

Wayne asked me to pull the line up anyway, intending to check if the fish had been smart enough to get away with the bait. But the shrimps were still there. And there was no fish on the hook.

REELING IT IN

Perhaps sensing my disappointment, Wayne cast his own line. Within a minute, he felt movement and passed his rod to me. I reeled it in and lo and behold, a fish appeared. Still, I was not content, determined to do it by myself.

I took a few more pieces of shrimp, bigger this time, and pierced it with the hook, careful to conceal the metal tip in the meat. It was as though I was willing myself to fool the fish. Then I cast my line.

Barely a minute passed when I felt my rod shake. I jerked it up, swiftly spinning my reel handle. Wayne was wearing a mask, but I could see his eyes lit up. The line emerged and brought with it a kind of yellow fish, no bigger than my palm. "Yay!" I squealed. "Oh, nice!" Wayne chimed in. It was my first ever official catch.

One of the anglers identified it as a diamond wrasse. I held it up to take a picture with it, admiring the dotted patterns on its body. But the sliminess and sharp spines meant it regularly slipped out of my palm.

Next, I needed to remove the hook from its mouth before placing it in a tub of water. The fish caught on Tuesday would be held there before being released at the end of the day.

Removing the hook turned out to be more difficult than I had imagined. The hook was embedded deep in its mouth, and I could not twist it out even after a few tries. I passed the fish to Wayne, who was starting to show some concern after 30 seconds without results.

Wayne put the fish in some water so it could it take a breather. Then he pulled it out again to try pulling out the hook. When even Wayne could not do it, he started asking for a pair of pliers. That was when Marine Stewards member Ryan Chin, 17, stepped in.

DOCUMENTING BIODIVERSITY

Ryan, who had initially approached the Marine Stewards with his idea for the sustainable fishing workshop, wrested the hook out after a few seconds, to the awe of the anglers that by now had surrounded us.

An avid angler since he was six years old, Ryan has travelled to the numerous jetties in Singapore after picking up fishing with his friends. Soon, he was surprised by the biodiversity he encountered.

"Singapore is blessed with over 500 species of marine fish, yet most of us don’t know they exist," he said.

Beyond encouraging sustainable fishing, Ryan said the workshop will also help the National Parks Board document different species of fish in an online database.

"It's more of like a census almost of the marine biodiversity that we have in the area," he explained, highlighting that such records currently do not exist. "Even if we know what we have, we don't know how much."

In addition, rarer species of fish caught during the workshop will be donated to the Lee Kong Chian Natural History Museum for research, Ryan said. One example is the leatherjacket fish that Wayne recently caught.

"This guy's really good at camouflage," Ryan said, showing me a picture of the leatherjacket fish and pointing to the grooves on its body. "These sorts of fish, they don't have much record of in Singapore."

BACK INTO THE WILD

As for my diamond wrasse, Ryan and the team decided that it was going back into the water.

The fish was now lying sideways in the tub of water. I looked at the anglers in horror, afraid that it was already dead. But Ryan assured me that the diamond wrasse loves to bury itself in the sand underwater, and that it was now mimicking this behaviour.

For my attempt at releasing fish, Wayne passed me a butterfly whiptail bream. Since it was a small fish, I simply had to pick it up and drop it over the water, he said, adding that bigger fish such as stingrays would need to be carried to shore first.

I picked up the bream, holding it in both palms as it struggled and almost escaped, and released it into the sea. I watched as it swam away quickly, finally understanding what this workshop hoped to achieve.

"We want to introduce the public to fishing and make the connection with sustainable seafood," Andrea said.

"It's also a good activity during the December school holidays, and it's something new for a lot of people. My personal take is that it's a very healthy sport."

The workshop will be conducted on nine days in December. Those interested can sign up on the Marine Stewards website.

Personally, Tuesday's session made me realise there was a point to catching a fish, beyond cooking it.

While I might have only caught a small fish, I could still somewhat feel the thrill of the hunt. The tension of wondering if you used an appealing bait or cast the line in the right area. The adrenaline rush when the fish struck.

With my fingers smelling of shrimp and my catch safely back in the water, I left the jetty feeling satisfied, knowing this would not be my first and last time fishing.