Government spending could exceed 20% of GDP by 2030; GST and other tax moves help to close funding gap: Finance Ministry

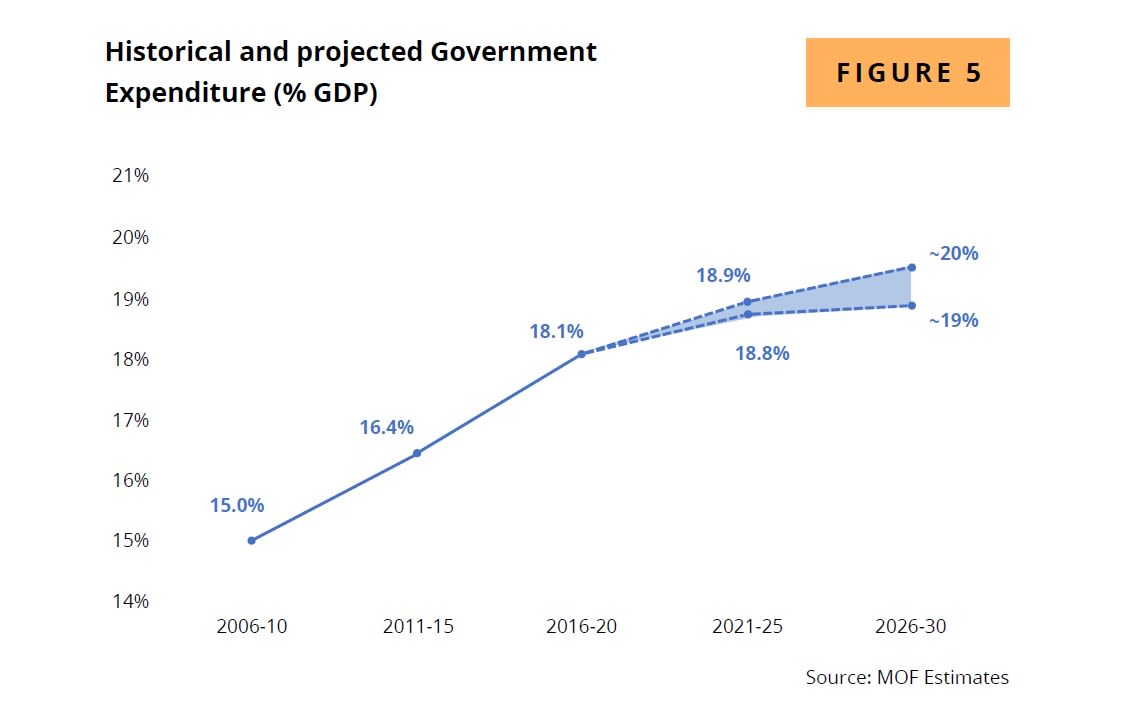

SINGAPORE: Singapore is expecting government expenditure to rise to about 19 per cent to 20 per cent of gross domestic product (GDP) between the financial years of 2026 to 2030, and possibly exceed 20 per cent by the end of the decade.

Healthcare will be a key driver of this anticipated increase in national spending, which currently stands at 18 per cent of GDP.

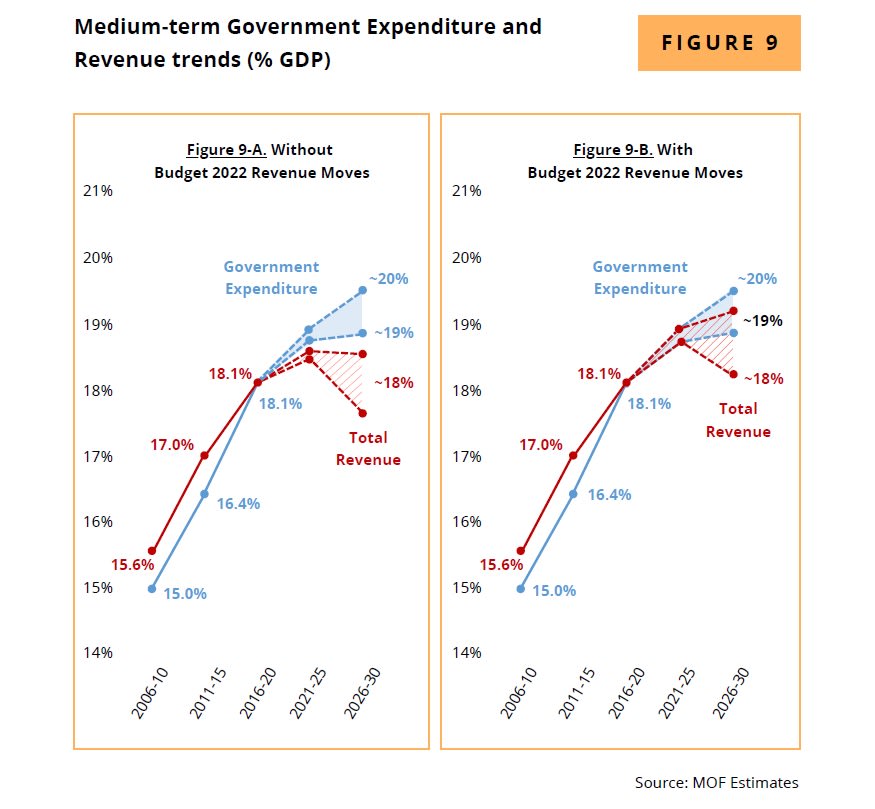

On the other hand, total government revenue – made up of operating revenue, such as tax and non-tax collections, and the Net Investment Returns Contribution (NIRC) – is now at about 18.5 per cent of GDP.

This revenue figure would not be sufficient to cover the increase in spending expected over the coming years, said the Ministry of Finance (MOF) in an occasional paper published on Wednesday (Feb 8).

The various tax changes announced in Budget 2022, which include the Goods and Services Tax (GST) hike and adjustments to some property tax and personal income tax rates, were therefore “necessary to close the funding gap”, said MOF.

These moves are set to yield additional revenues of about 0.7 per cent of GDP a year.

“Without the revenue moves made in Budget 2022, total revenue would have fallen below the projected level of government spending within this decade,” the ministry said.

But MOF also cautioned that the forecasts in its occasional paper do not take into account future policy moves that may be needed to address the various challenges ahead.

These challenges include an external environment marked by slower labour productivity growth, greater competition for global investments and geopolitical tensions.

Domestically, Singapore is seeing a rapidly ageing population that requires not just more investments in healthcare but also upgrading in infrastructure. More has to be done as well in areas such as training for workers and strengthening social support amid greater uncertainties and disruptions.

In addition, there is unlikely to be a repeat of the high economic growth and large fiscal surpluses of the 1990s, said MOF, which means Singapore’s “fiscal space is now much tighter” compared to the past few decades.

Hence, in the event of further spending increases, Singapore “will need additional revenues to balance the budget in the medium term”, said MOF.

EXPENDITURE ESTIMATES

Laying out the medium-term projections for expenditure, the ministry noted that healthcare spending is estimated to jump to about 2.9 per cent to 3.5 per cent of GDP between 2026 to 2030 on the back of an ageing population, higher utilisation of healthcare and medical inflation.

Currently, healthcare expenditure, excluding pandemic-related costs, stands at about 2.3 per cent of GDP.

Likewise, infrastructure spending, which has already risen to around 4 per cent of GDP due to major, long-term projects such as the building of new MRT lines, will go up further to 4.4 per cent in the coming years.

The Government in 2021 introduced the Significant Infrastructure Government Loan Act (SINGA) to allow borrowing for major and long-term infrastructure projects, with the aim of spreading out costs “more equitably” across generations.

With SINGA, the fiscal impact of these projects is set to remain at around 4 per cent of GDP per annum between 2026 to 2030. But MOF said this is “subject to some uncertainty” as higher interest rates in the medium term could raise borrowing costs and hence projected spending.

For the remaining components of government spending, MOF expects them to grow “at least as fast as GDP” assuming no major policy changes.

The projections also factored in spending commitments already made by the Government, such as more than doubling the annual spending on early childhood education in the next few years and the uplifting of lower-wage workers through schemes such as the enhanced Workfare Income Supplement.

Taken together, the Government’s expenditure is estimated to increase to around 19 per cent to 20 per cent of GDP between 2026 to 2030.

When compared with other advanced economies, this overall expenditure as a percentage of GDP is “relatively small” and reflects the Government’s focus on “fiscal prudence and cost-effective spending”, MOF said.

REVENUE ESTIMATES

On the revenue front, MOF expects operating revenue, which is now at about 15 per cent of GDP, “to grow slightly slower than GDP” in the absence of policy changes.

This means that “periodic moves to increase revenue would be needed” if expenditures continue to outpace GDP growth, the paper wrote.

Another big contributor to government coffers is the NIRC, which comprises up to 50 per cent of the net investment returns on net assets invested by GIC, the Monetary Authority of Singapore and Temasek, and up to 50 per cent of the net investment income derived from past reserves from the remaining assets.

The NIRC has averaged around 3.5 per cent of GDP per annum over the last five years, and it is expected to remain at about the same share of GDP over the coming years.

Another thing to consider will be changes in global tax rules as a result of the Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS 2.0) initiative, although this was not factored in the projections of this paper given the uncertainties ahead.

BEPS 2.0, a plan led by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development with the aim of curtailing profit shifting by multinational companies to lower-tax jurisdictions, has proposed two changes.

First, to ensure firms pay taxes in countries where they earn their profits, regardless of whether they have a physical presence. This will see Singapore losing revenue given its small market size, MOF said.

Second, to set a minimum corporate tax rate of 15 per cent for large multinational enterprises. Singapore has said it will explore a “top-up” tax in response to this.

In this case, MOF described the long-term revenue impact as “uncertain”, depending on the response of governments and businesses. At the same time, any additional revenue collected from this is expected to go into enhancing Singapore’s economic competitiveness as the fight for investments through non-tax measures intensifies.

Aa a result, the net fiscal impact of BEPS 2.0 on Singapore “may not be favourable”, it added.

“MAY NEED ADDITIONAL REVENUES”

MOF noted that its projections in this occasional paper show “a picture of rising Government spending being balanced by total revenue in the coming years”.

“But we have not taken into account possible further policy moves that the Government may make between now and 2030, for which the resource requirements are yet to be determined,” it added.

“Depending on the final design and scale of these moves, we may need additional revenues to balance the budget in the medium term.”

Noting that fiscal strength is “a key competitive advantage” for Singapore, MOF said the Government will continue to review and adjust its fiscal strategies to support “shared aspirations in a way that is fair to both present and future generations of Singaporeans”.