Most accusations made against maids by employers do not lead to criminal charges: HOME report

“Revenge accusations” and the power that employers hold over foreign domestic workers were among issues flagged by the Humanitarian Organisation for Migration Economics.

File photo of foreign domestic worker maid sending children to school in Singapore (Photo: CNA/Javier Lim)

SINGAPORE: A majority of migrant domestic workers whose employers accuse them of criminal offences – mostly theft – are ultimately not prosecuted in court, according to a study conducted by migrant worker rights group Humanitarian Organisation for Migration Economics (HOME).

While waiting for the outcome, these maids “suffer the heavy consequences” of the accusations, such as spending months in a shelter and not being allowed to work, HOME noted in a report on the study released on Tuesday (Aug 15).

The non-governmental group analysed 100 cases where domestic workers were accused of a crime in order to determine patterns that affect their lives and livelihoods.

The report also sought to highlight the amount of power employers hold over their maids’ circumstances, as well as the fact that maids are subject to different norms within the criminal justice system due to the “unique precarity” of work permit holders.

HOME added: “Importantly, the findings demonstrate how the police is used as a threat, and punitive – and often retaliatory – tool against migrant domestic workers.”

The study came on the back of a high-profile case involving former domestic worker Parti Liyani, who worked for ex-Changi Airport Group chairman Liew Mun Leong.

Ms Parti was convicted of stealing S$34,000 (US$25,100) worth of items from Mr Liew and his family, and sentenced to 26 months’ jail. She was first charged in 2016.

The conviction was overturned by the High Court in September 2020, eventually leading to Mr Liew’s son – Karl Liew – being sentenced to two weeks’ jail earlier this year for lying during Ms Parti’s trial in the State Courts.

Ms Parti was not allowed to work and spent four years in HOME’s shelter. She has since returned to her home country of Indonesia.

STUDY FINDINGS

HOME examined data from 100 domestic workers who stayed at its shelter between January 2019 and June 2022 and were the subject of criminal investigations.

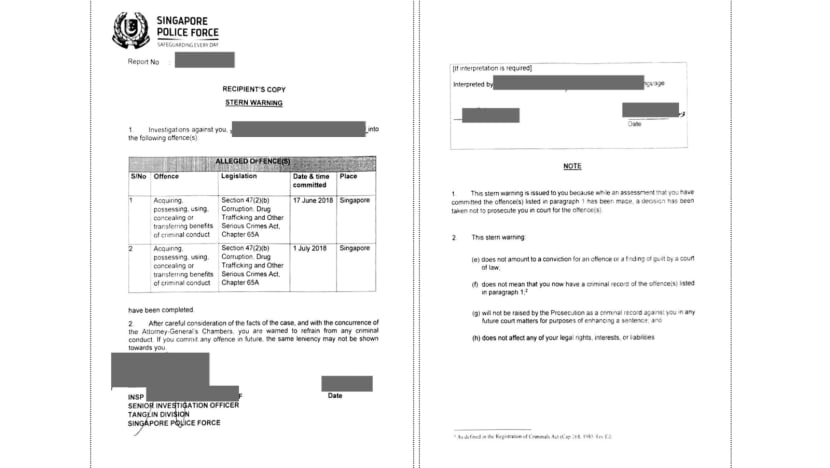

Of these maids, 82 were not formally charged with the crime they were accused of. These comprised 43 who were given a stern warning, 36 cases where no further action was taken, and three cases that were dropped.

This means that accusations only led to a formal charge 18 per cent of the time.

The average length of stay at the HOME shelter for accused domestic workers was four months. Among those studied by HOME, 14 stayed for eight to nine months, while three stayed for more than a year.

Meanwhile, the most common type of accusation was theft, making up 71 per cent of all cases. The others involved alleged offences like physical abuse or moneylending.

Theft accusations were typically petty in nature, involving small or insignificant items and monetary sums, HOME said.

In one case, an employer filed a police report to accuse her domestic worker of stealing S$10.

“Accusations of theft can be made very easily, require little to no proof, and do not negatively impact employers – regardless of the outcome – while having disproportionate and potentially disastrous outcomes for migrant domestic workers,” HOME stated in its report.

It noted that domestic workers have a different experience of the criminal justice system in comparison to the local population.

When the authorities begin investigating them, many no longer stay with their employers and are made to stay with their agents – or, in most cases, a shelter.

During this period, they are put on a special pass and are not allowed to work, except if the investigating authority decides otherwise.

“In effect, simply being accused puts the livelihoods of these migrant domestic workers at risk, as it interrupts their employment and they are detained in a liminal location for an indefinite period of time,” said HOME.

REVENGE ACCUSATIONS

HOME also highlighted a trend of “revenge accusations”.

These refer to allegations directed at domestic workers by their former employers after they ended their employment and left their employers’ homes, and for which no further action was usually taken against the domestic worker.

Among the accusations examined by HOME, a fifth – or 20 – of them were made by employers after the domestic workers arrived at the HOME shelter. A vast majority were for theft.

Only three were eventually charged in court, while five were themselves being investigated as a victim of a crime by the employer.

Some had also left their employers’ homes as they could no longer tolerate the living and working conditions there.

“The timing of these accusations, in addition to the nature of the accusations and their outcomes, suggest accusations may be made in retaliation,” said HOME.

One maid, identified as R1 in HOME’s report, sought help from HOME after her employer refused to repatriate her for a year. When she returned to the employer’s home to retrieve her belongings, the employer accused her of stealing money and called the police on the spot.

Due to the investigation, she had to stay in Singapore for another nine months, only returning home when the authorities decided not to take further action.

HOME referred to a separate report it released last year on the emotional abuse faced by domestic workers, where interviewees described how employers frequently threatened to call the police and have them blacklisted in Singapore.

“Employers have considerable power and influence over a migrant domestic worker's work, income, residential and generally social status, (and) are aware of the disproportionate influence and impact over migrant domestic workers that the current system affords them,” HOME noted.

“In cases where employers are mistreating migrant domestic workers, they are able to use that influence in exploitative, penal, and even vindictive ways that unfairly impact migrant domestic workers.”

According to the Ministry of Home Affairs, roughly two accusations of theft were levelled against maids every three days in 2016. About one-quarter of these maids were prosecuted that year.

This phenomenon was not new or exclusive to Singapore, said HOME. A similar study was conducted in Lebanon in 2011 where employers were found to have reported runaway domestic workers for theft, despite a lack of evidence, in order to escape the costs of repatriation.

In Ms Parti’s case, the High Court judge who overturned her conviction found that her employers had likely accused her of theft in retaliation for her threats to report the family to the Ministry of Manpower for illegal deployment.

HOME also noted that domestic workers who receive a stern warning are typically barred from working in Singapore, even though the High Court has made clear that a stern warning does not amount to a conviction or finding of guilt.

Nevertheless, the group said it has seen more accused maids being allowed to work since the second quarter of last year. Two maids who received stern warnings were also given permission to work last year.

RECOMMENDATIONS

HOME gave four recommendations to address “systemic issues” in regard to domestic workers’ living and working conditions.

The first was to allow maids who are assisting in investigations to work. They are currently put on a special pass issued by the investigating authority, with their ability to work often being determined at the discretion of individual officers, said HOME.

The second was to allow maids who have been given stern warnings to work. Work permit holders who receive stern warnings are generally disbarred from seeking employment in Singapore.

HOME also suggested that maids be given the option of living away from their employers, so they are less susceptible to accusations against them.

The group's final recommendation was to give maids the right to change employers with clearly defined notice periods, and upon the expiry of their work permit terms, without their employers’ consent.

They are currently required to get their employers’ consent to switch employers, even at the end of their work permit terms.

"For the average individual, a criminal accusation can be stressful, damaging, and even traumatic," HOME noted.

"For migrant domestic workers, whose legal, financial, and social positions in Singapore are already tenuous and precarious, it is exponentially more harmful due to the loss in their livelihoods, income, housing as well as their current and future work status in Singapore."