Crucial to minimise inevitable harm to marine environment if Long Island reclamation project proceeds: Experts

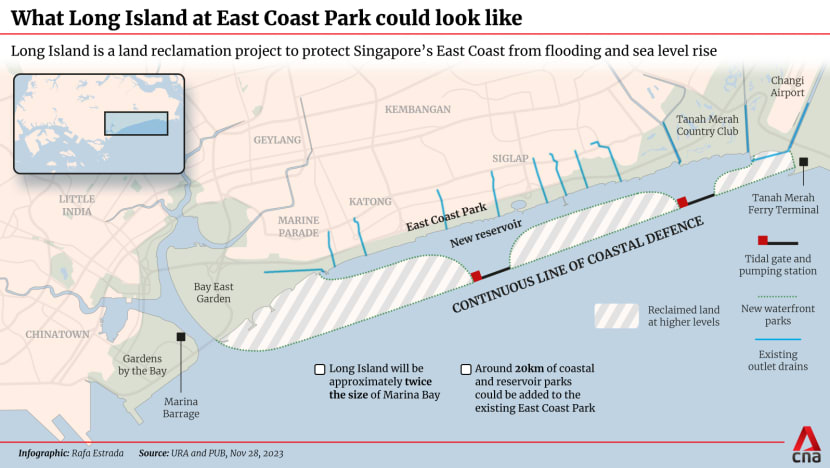

The decades-long project off East Coast Park could involve the reclamation of around 800ha of land – twice the size of the downtown Marina Bay area.

A section of East Coast Park as seen in May 2021. (Photo: CNA/Louisa Tang)

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

SINGAPORE: With decades of reclamation works having previously devastated marine life along Singapore's eastern coast, environmental experts told CNA it is crucial to make certain that construction on the “Long Island” reclaimed site would not significantly impact sensitive marine habitats like coral reefs.

Experts also stressed the need for the government to engage nature researchers, non-governmental organisations and the public from an early stage in order to protect biodiversity and prevent loss of habitat at East Coast Park, as well as the nearby Southern Islands.

This comes after Singapore on Tuesday (Nov 28) announced plans to begin technical studies for the decades-long project off East Coast Park which could reclaim around 800ha of land – twice the size of the downtown Marina Bay area.

The studies, to begin in 2024, will involve extensive environmental and engineering studies to see if the conceptual reclamation profile is feasible, and for the authorities to formulate innovative and cost-effective nature-based solutions.

The Long Island plan is meant to protect the current coastal zone and inland areas at East Coast from being inundated by seawater in the future.

Studies have projected a rise in mean sea level of up to 1m by 2100. Combined with possible high tides and storm surges, sea levels could rise by 4m to 5m, threatening low-lying Singapore's shorelines.

The effects of high sea levels at East Coast Park – Singapore's largest park with a span of about 13km – are already being felt. In 2018 and in January this year, swathes of the park were flooded due to rain and high tide.

POTENTIAL IMPACT

The process of reclaiming land from sea “would certainly lead to the decline of marine species living in the sea and potentially habitats around it”, said Associate Professor Huang Danwei from the National University of Singapore (NUS).

For example, half of coastal wetlands in China have been lost to land reclamation.

The deputy head of Lee Kong Chian Natural History Museum, whose research interests include coral reef ecology and conservation, cautioned that Singapore needs to strike a balance between coastal protection and marine life protection.

“Certainly, lives, livelihoods and properties are at stake, but terrestrial and coastal ecosystems that may be affected by the seawater inundation in the next few decades could also be impacted,” added Assoc Prof Huang.

“These should be balanced by the potential impact on sea life directly at the areas of reclamation and also marine ecosystems adjacent to these areas.”

Land can be reclaimed by adding material such as rocks, soil, and cement to an area of water. It can also be achieved by draining submerged wetlands or similar biomes.

Stephen Beng, the chairperson of the Friends of the Marine Park ground-led initiative, concurred that reclamation works on Long Island will "most definitely" disrupt ecosystems and lead to a loss of habitat and biodiversity.

He noted that Singapore lost 60 per cent of its coral reefs, which “support a greater diversity of life than any place on earth”, over the past few decades due to reclamation and development works.

A vast majority of these reclamation works have happened along the eastern coast, such as the East Coast Reclamation Scheme that was launched in 1966. It was completed 20 years later with a total of 1,525ha of land reclaimed.

With the Long Island project slated to be a similarly decades-long one, more sediment and pollutants could end up in the waters. This could smother corals and seagrasses and impact the Southern Islands, which is home to most of Singapore's remaining coral reefs, said Dr Jani Tanzil, facility director of St John's Island National Marine Laboratory.

Aside from the past loss of coral reefs, she noted that reefs in Singapore already exist "in marginal conditions where light penetration is limited".

"I'm worried that if the land reclamation works are not managed properly, we may see our reefs having to endure even lower light conditions for decades to come, and further truncation of our reefs to even shallower vertical distribution," Dr Jani added.

NUS biological scientist N Sivasothi also pointed out that the Long Island project will eliminate existing marine habitats, given the plans to create an enclosed waterbody – eventually, a freshwater reservoir – in front of East Coast Park.

Nevertheless, he said these marine communities are not as mature as those on Chek Jawa Wetlands or Pulau Ubin.

Mr Beng added: “We’ve … seen that life on our reefs and shores does return when given a chance, though some changes and losses cannot be reversed such as predator-prey relationships, invasive species, resource competition.

“Our remaining reefs and living shores could disappear within a generation under the threats of climate change and coastal development."

DESIGN WITH NATURE FIRST IN MIND

The experts championed the idea of designing structures at Long Island with a nature-first approach, including artificial reef structures that can beef up coastal defence and biodiversity protection.

Mr Beng further suggested providing sufficient depth for mangroves, slopes of reefs, and allowing the natural accumulation of sediment for sandy beaches and rocky shores.

Professor Benjamin Horton, director of the Earth Observatory of Singapore, also pointed to "working with nature" concepts where developments are designed based on natural principles that mimic nature.

Marine forces – such as waves and tides – should be used to maintain high-quality developments like artificial beaches, lagoons, wetlands and mangroves, rather than being viewed as something to protect against during extreme events, he added.

"Coastal environments are transient, continuously reshaped by the natural forces of waves, tides, surges, erosion and deposition. To be sustainable, the Long Island developments must be designed and implemented with a clear understanding and respect for local natural processes," Prof Horton noted.

Mr Beng cautioned that Singapore must not "become comfortable with the ability to reclaim and restore", despite coming far to include conservation considerations in development plans.

Time must be given between work phases for the environment to recover, and the government must also continuously monitor environmental and social impacts over a wider area, he said.

This is especially because the Sisters’ Islands Marine Park – part of the Southern Islands – will be exposed to much of the risks during reclamation and construction works, and may also face changes in water quality and flow.

“Nature is most resilient to disturbances when it’s left natural,” Mr Beng noted.

“If climate adaptation and future development come at a greater cost to nature, then that could also mean an unrecoverable expense for all of us.”

Whether or not Singapore's environment will benefit from having another island, where flora and fauna can flourish, is up in the air for now.

Assoc Prof Huang said a comprehensive environmental impact assessment is needed to determine the biodiversity costs.

He added: "An artificially created land area with additional coastal space is not the same as natural ecosystems that have been around for thousands of years in terms of biodiversity and their natural functions and services, even if the island might be designed to host biodiversity with an abundance of greening efforts."

"URGENT RESPONSIBILITY" TO ADDRESS SEA LEVEL RISE

Mr Sivasothi pointed out some key differences in the preparations and design for the Long Island project compared to reclamation works from decades ago.

For example, there is a desire to integrate relevant terrestrial and marine nature areas with the project. Much more is also known about the restoration ecology of terrestrial and marine environments from both local and global studies, which means Singapore can “ensure the facilitated establishment of nature areas unlike before”, added Mr Sivasothi.

He also spoke of being heartened to see during a recent engagement that the push to protect and integrate biodiversity in the Long Island project not only came from members of nature groups, but from many other participants.

“The responsibility to address sea level rise is a critical and urgent responsibility of this time,” Mr Sivasothi pointed out.

“An island state like Singapore with high population density and no hinterland is much more vulnerable than most other countries, and global action to address global warming deadlines is always behind schedule. So, it is welcome that we initiate plans to prepare the country.”

Prof Horton said that land reclamation can be done safely and with minimal – even positive – impact through appropriate site selection, master planning and support studies.

"It is also key to engage with stakeholders to get their views, concerns and expectations. Creating Long Island will take time," he added.

Editor's note: This article has been updated to reflect that Stephen Beng no longer holds the position of chairman of the Nature Society.