Oil along Singapore's coasts? How NEA officers dip into drains and canals to trace sources of pollution

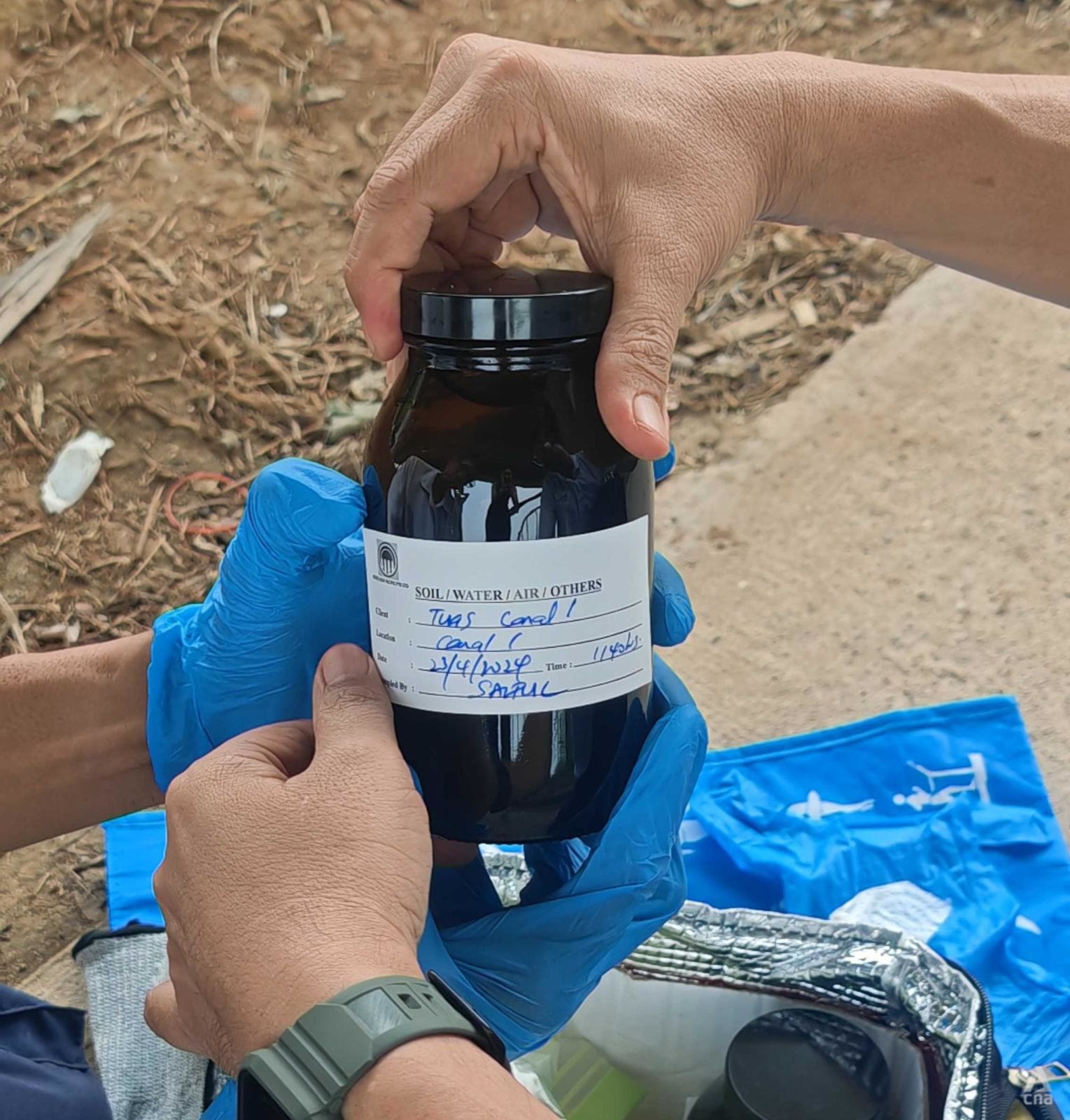

The National Environment Agency shows CNA how it collects and stores water samples to be tested.

NEA officers dipping a jar fixed to a pole into Tuas canal to collect water samples which they will send to a lab to test for pollution. (Photos: CNA/Koh Wan Ting)

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

SINGAPORE: At the side of a canal in Singapore's far west, a man holds with both arms a pole, ready to lower an attached jar beneath the water's dark, scummy surface.

He's an officer from the National Environment Agency (NEA), tasked with the unenviable job of collecting samples to be tested for pollutants like oil and grease.

NEA regularly monitors the water quality of both inland water bodies and coastal areas, checking for pH - the level of acidity - and other markers such as dissolved oxygen and metals.

Alongside this, the statutory board under the Ministry of Sustainability and the Environment also investigates reports of pollution, and is responsible for tracing the culprits contaminating Singapore's waters.

Between 2019 and 2023, NEA prosecuted 33 such companies. They were from construction or other industries using heavy machinery, and were issued warning letters, composition fines or taken to court.

Investigations and enforcement could span months, with officers sometimes having to trawl and collect samples from any combination of drains, canals, or coastal areas, to trace the source of the pollution.

Earlier this year for example, oil slicks were reported off Tuas Port. Investigations are still ongoing, with initial findings suggesting that the source was inland.

SAMPLING EVERY DRAIN

Donning blue rubber gloves and safety goggles, two officers from NEA's inspectorate department work as a pair to collect water from Tuas Canal, which leads to the sea.

NEA's deputy director of its pollution control division Zhang Kang En told CNA that ahead of such trips, officers would have already planned the locations, timing, collection frequency and parameters to be tested.

At the collection point, an open glass jar - used for oil and grease testing - is strapped to a contraption at the end of an adjustable pole, and dipped beneath the water.

On site, officers check for a healthy range of oxygen in the water, the level of acidity and for the presence of dissolved salts. Changes in these factors may indicate a deterioration in the water quality.

The jar holding a collected sample is then labelled and carefully placed into a cooler bag with ice, to slow down chemical and biological degradation.

The work doesn't end there.

"Officers will have to record details of samples in their record books. They will also record other observations which they see during the sampling. For example, the condition of the water, weather, whether they see any visible sources of contamination," said NEA's Zhang.

He added that officers are careful to avoid collecting debris such as leaves and sand. They also avoid "dead zones" - parts of the water with poor circulation - and points where water bodies converge. Samples collected from such spots will not be an accurate representation of the water body.

In cases where officers encounter dead fish, NEA may work with other organisations such as the Singapore Food Agency to collect fish samples for post-mortems.

LABORATORY WORK

Over at the STATS Asia Pacific testing lab contracted by NEA, employees preside over an array of glass equipment straight out of a chemistry lesson.

To test for contamination, chemist Lee Woan Qi and her colleagues undertake a series of steps to separate and then measure the oil and grease in the water sample, using a micro-pipette, separating funnel, filter paper and a volumetric flask.

For the separation process, the chemist adds a solution and solvent into 1,000 ml of the water sample, held in an upright separating funnel.

The solution is meant to acidify the water, to help the solvent stick to the oil and grease, so that these can be filtered out later.

The chemist then caps the separating funnel, mindful to release pressure from the gas, and shakes the conical glass funnel vigorously for a minute, to let the contents mix.

The solvent with the oil and grease settles at the bottom of the separating funnel as it is denser than water. It is then drained into a volumetric flask through a piece of filter paper.

The process is repeated twice, to drain as much of the oil and grease from the sample as possible.

Once 100ml is obtained in the volumetric flask, the chemist inverts it to check for a layer of water. Water would mean that the process of separating oil and grease has failed, and will have to be redone.

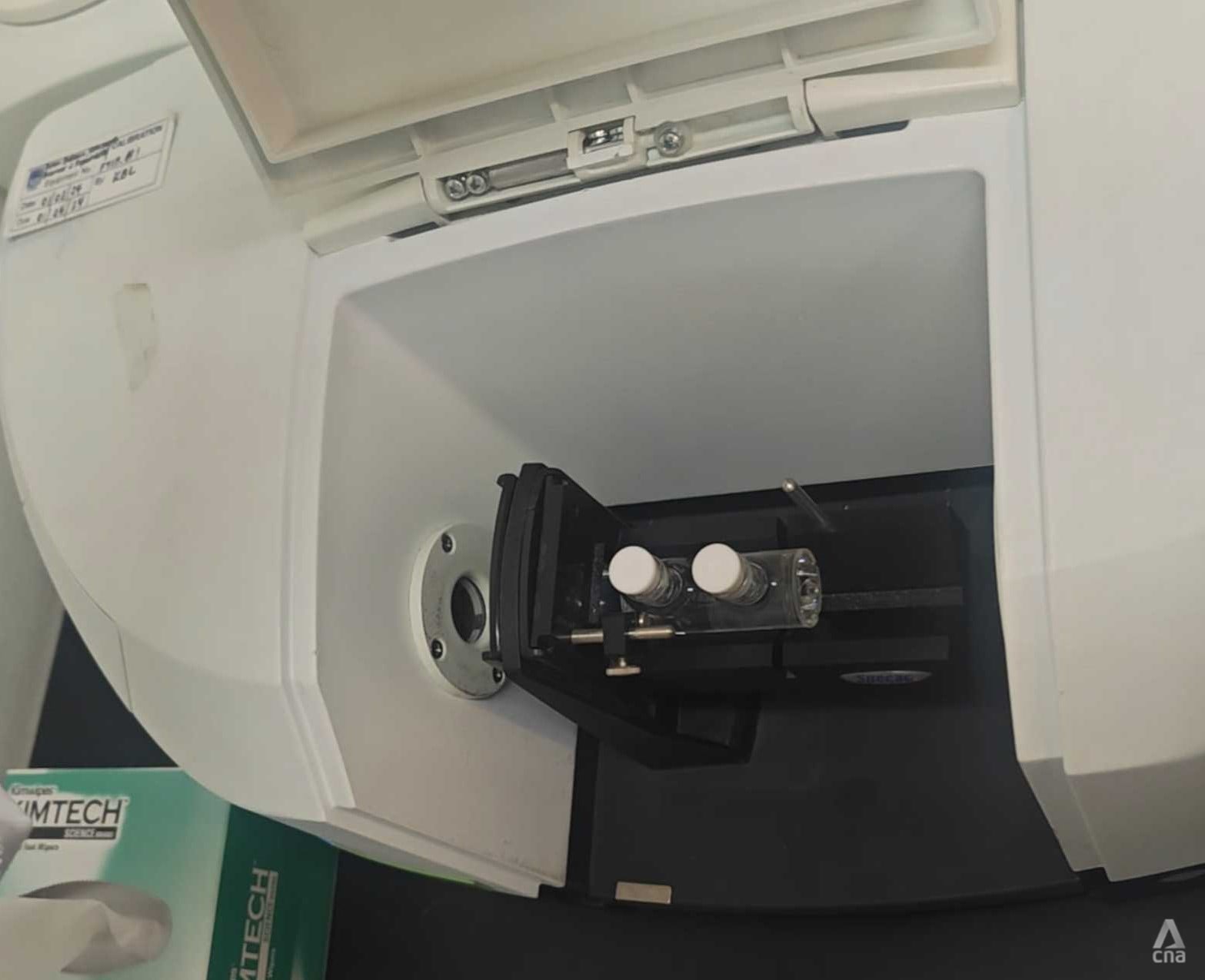

If not, the solvent with the oil and grease is poured into a glass vial. This glass vial is then placed into a machine that uses infrared to measure the amount of oil and grease present. Results are sent to NEA.

INVESTIGATIVE WORK

The task of sample collection gets more tedious when the source of contamination is not immediately clear - such as in the case of the oil slicks off Tuas Port.

With so many factories in the vicinity, the NEA team has to work through a list of suspects, focusing on companies that handle large volumes of oil or wash oily machinery.

When a source is identified, officers need to secure access to the factory premises to conduct more checks, and to interview management and workers to get a sense of what caused the discharge.

Investigations are even more challenging when companies are evasive or intentionally polluting waterways.

"Many years back, there was an incident where a company actually brought toxic industrial waste out to a very deserted part of Singapore, and just opened the tap on the intermediate bulk containers and allowed (it) to just flow out into the drain," Mr Zhang from NEA recalled.

Asked how the agency deals with an offending company deliberately withholding evidence or being uncooperative, he said: "We will definitely have the evidence to say that they have caused the discharge... they will have to explain to us why they have allowed their workers to do that. Why didn't they maintain the equipment properly? Why did they allow the worker to bring the containers out at night?"

"They will have to tell us the whole story," Mr Zhang added. "So there's a lot of investigative work that we are trying to do."

Apart from inland water bodies, NEA monitors water quality out at sea through Project Neptune, a network of eight large buoys armed with sensors and located between 200m and 3km away from Singapore's shoreline.

The buoys can help detect oil spills, identify where oil particles are coming from, and where they might end up based on current and wind conditions, among other factors.

"Based on the outcome of the model, we're able to identify the likely shoreline area where the oil slick or tar balls could be deposited," said NEA's director of its environmental monitoring and modelling division Jelita Teper.

"This will enable us to notify our colleagues from the Department of Public Cleanliness to deploy their cleaning contractors to the affected shoreline for cleaning operations."

And to collect water samples, you can count on officers from the agency's inspectorate department to show up in no time.