In the underbelly of e-commerce sites, 'cyber spotters' are hunting down illegal wildlife listings

With illegal wildlife trade the fourth largest global crime, the average individual can feel powerless to help. Enter WWF Singapore's cyber spotter programme, an "accessible" way for volunteers to make an impact – from their own laptop.

An image of a live tiger cub in a suitcase from an actual case of smuggling, used for WWF Singapore's cyber spotter training. (Photo: CNA/Grace Yeoh)

SINGAPORE: Mr Kaustubh Srikanth was not prepared for the day he saw a live pangolin enclosed in a cage being sold online.

The 30-year-old lead trainer for World Wildlife Fund (WWF) Singapore’s cyber spotter programme – made up of volunteers who are trained to help spot illegal wildlife trade listings online – recalled being “quite taken aback” by the shocking image.

Experts estimate that about a million pangolins have been sold illegally over the last decade for its meat and scales, making it the most trafficked mammal in the world.

But Mr Kaustubh's desire to protect such animals started even before he saw the image. The Mumbai native grew up around wildlife like leopards, wildcats, snakes and birds.

Two years into his role at WWF Singapore, where he also handles education and outreach, he has grown familiar with the graphic nature of his job.

Some listings are more explicit, marketing the live animal using a photo or video and sharing the name of the illegal wildlife trade product. Other times, listings are hidden behind “visual illustrations or nicknames” or may only show a generic image from Google with the description stating that the seller has a “live animal in stock”.

When new volunteer cyber spotters first chance upon such listings, they often have an emotional reaction too. For many of them, it can be “very stressful” to see a “cute” animal in a cage, said Mr Kaustubh.

“The first time we train (the volunteers), they are completely shocked that something like this can exist online. Everyone has always known that illegal wildlife trade exists physically, but then they happen to see so many products and collections online, and they get very, very disturbed,” he added.

Yet, this is often the turning point for many cyber spotters, who become more determined to play a part in stopping illegal wildlife trade.

TARGETING ILLEGAL WILDLIFE TRADE ONLINE

Wildlife crime is one of the most lucrative illegal businesses in the world today. It is the fourth most profitable illicit trade worldwide, estimated at up to USD$23 billion annually, according to a documentary from WWF Singapore on tackling illegal wildlife trade that was released in November.

It is also “often linked to crime syndicates”, WWF Singapore told CNA.

But the issue was recently put in the spotlight again when Singapore authorities in October seized around S$1.2 million worth of rhinoceros horns that were being smuggled through Changi Airport.

That same month, a man travelling from Germany to Singapore was caught by security officers at Munich Airport for smuggling a live albino alligator wrapped in cling film in his suitcase.

“Singapore’s role as a major trading hub for the region makes the city-state a convenient location and through-route for illegal wildlife trade and products,” explained Mr Kaustubh.

As such, his cyber spotting team must keep abreast with broader trends. For instance, Singapore banned domestic trade in elephant ivory from September 2021 so they don’t see “too many” ivory listings in Singapore, but such listings still prevail in Southeast Asia.

Digital spaces can also add complications, suggested Mr Kaustubh. They fuel the “anonymous nature” of online trafficking; purchasing elephant ivory, tiger teeth and other endangered wildlife products can be "done with a simple click”.

“It is essential that e-commerce and social media platforms take charge of detecting and tackling this illegal trade,” he said.

To that end, WWF in 2018 joined forces with wildlife trade monitoring network TRAFFIC and the International Fund for Animal Welfare (IFAW) to launch the Coalition to End Wildlife Trafficking Online with about 20 tech companies.

By October 2022, the coalition had expanded to almost 50 companies with operations around the world to combat illegal wildlife trade, including Alibaba, Baidu, Lazada, Meta and TikTok.

In November 2020, WWF Singapore conducted a pilot round of the cyber spotter programme for coalition member employees after it was first introduced in the US “to help them identify illegal wildlife trade products, train their own artificial intelligence system and update their company policies”, said Mr Kaustubh.

“SO EASILY FOUND ONLINE”

WWF Singapore’s cyber spotter programme has today trained more than 325 volunteers and flagged more than 14,500 illegal wildlife trade listings.

The programme, which requires volunteers to have a residential status in Singapore and be above 18 years old to apply, comprises five rounds each year. Each round lasts four weeks, and the next will be held in February 2023.

Through volunteering for the programme, many volunteers realised that combating illegal wildlife trade was “not just at the ranger level” and that they could also “take ownership of wildlife protection”. Cyber spotting was a “very accessible way to help”, added WWF Singapore.

When Sherlene (not her real name) first started volunteering in July this year, she only found “rhinoceros horns, ivory and the like”. Then she tried looking for live listings, and was “appalled” at the “atrocious living conditions” in which live animals were kept.

“They deserve to live freely in the wild. Viewing these live animal listings really solidified my will to continue with the programme,” said the cyber spotter who has been juggling school alongside her cyber spotting commitment.

“Even though I may not be making a large-scale policy difference, I make a difference to those (listings) I flag and that's enough to keep me going,” she told CNA over email.

Similarly, another cyber spotter Aaron (not his real name) said he was shocked to learn that such listings are “so easily found online”.

Since becoming a cyber spotter in June last year, he has found “turtle meat, baby animals looking sad in cages, tons and tons of elephant ivory”.

“We need to be able to search for illegal wildlife trade product listings in ecommerce platforms, and I am pretty well versed in how to find things online, so I thought I would give it a shot and volunteer my time for this," the volunteer in his late 30s said over email.

Over time, Aaron noticed keywords or “popular types of listings” no longer online, which indicated to him that “the platforms are taking action to remove or ban these sorts of listings”.

HOW WWF'S CYBER SPOTTERS ARE TRAINED

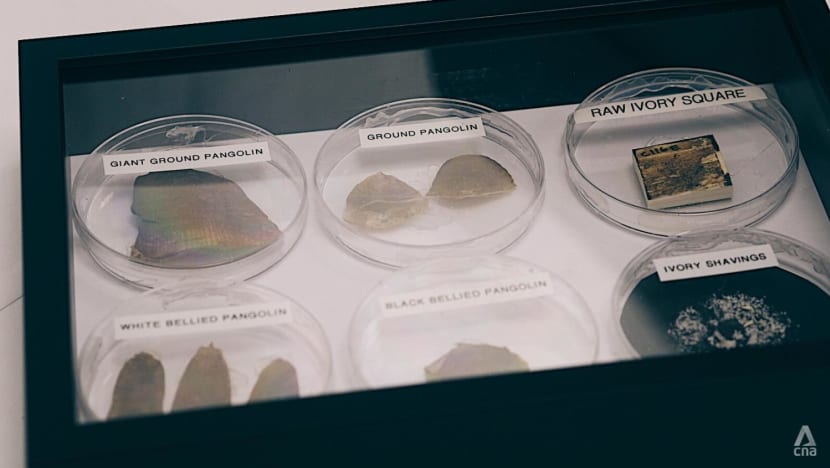

Over an initial two-day training, volunteers are given “focus areas” so they know what to search for. These include elephant ivory and non-ivory products like elephant hair or elephant leather, claws and teeth from wildcats such as tigers and leopards, as well as pangolin scales and the live pangolin itself.

Volunteers have since flagged listings of other live animals, such as ball pythons, leopard geckos and the Indian star tortoise. The Indian star tortoise is listed in Appendix I of CITES.

CITES is the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora, an international agreement to protect endangered plants and animals. Appendix I includes all species threatened with extinction, which are or may be affected by trade.

Since the cyber spotter programme kicked off in 2020, there have been more than 340 new search keywords.

“This is something that requires constant action, because the focus areas that we look at and the animals that we try to search keep evolving based on the latest trends. We need to keep ensuring that we are searching according to what the trends are,” said Mr Kaustubh.

To further help them in their search for listings, volunteers are given a “very well-defined resource kit” with a “step-by-step process”, as well as taken through live training sessions. Some repeat volunteers also share their strategies for flagging these products.

Above all, volunteers are reminded to stay safe. They are told not to engage with sellers, and to try keeping their search to the e-commerce platforms that are part of the coalition, added Mr Kaustubh.

USING SCIENCE AND TECH TO INVESTIGATE WILDLIFE TRAFFICKING

After verifying the listings flagged, WWF Singapore first shares them with the respective e-commerce platforms to remove them. Listings of repeat “offenders” are shared with law enforcement.

Over at the National Parks Board's (NParks) Wildlife Trade Branch, director of wildlife trade Anna Wong and her team jump into action when they get wind of such listings.

“We will monitor and then we will contact the seller or see how we can locate the seller. Sometimes the name doesn’t have a handphone number; there’s nothing at all. But if there’s a handphone number, we can try to see whether we can get an address or contact them,” Dr Wong told CNA.

Once illegal wildlife trade products are confiscated, NParks sends them to the Centre for Wildlife Forensics (CWF) – Singapore’s national facility that uses science and technology to investigate cases of illegal wildlife trade.

Building on the work of the Centre for Animal and Veterinary Sciences, CWF’s enhanced testing capabilities aim to “accurately identify the species seized” and “provide deeper insights on the seized items, such as their geographical origins”, said NParks in its media release about the facility, which opened in August 2021.

For instance, studies done with Professor Samuel Wasser from the University of Washington found that most of the large ivory seizures made globally over the last decade came from “repeated poaching at the same location”, and even from the same families of elephants, added NParks.

By revealing the “criminal networks” operating in source countries, source countries can focus on tackling “elephant poaching hotspots” and the illegal export of ivory, while destination countries act to curb consumer demand for ivory products.

But not everything is a big seizure, added Dr Charlene Judith Fernandez, director for the Centre for Animal and Veterinary Sciences, whose team also does laboratory work for CWF.

"There’s the day-to-day work as well. The whole point is to make the detection skills better, more sensitive, more specific. ... For example, you can’t argue with the raw ivory, but once it starts to be carved, (authorities) ask if it’s ivory or resin or bone. We’ve had to help to differentiate that," she shared.

But it's the “heartbreaking” cases that have stuck with Dr Wong’s team, such as the three major seizures in April and July 2019.

In April that year, NParks and Singapore Customs inspected a container on the way from Nigeria to Vietnam that was declared to contain “frozen beef”, only to find 12.9 tonnes of pangolin scales and 177kg of cut up and carved elephant ivory. Later that month, NParks, Singapore Customs and ICA uncovered 12.7 tonnes of pangolin scales in another container.

And in July 2019, authorities found 11.9 tonnes of pangolin scales and 8.8 tonnes of elephant ivory in three containers – amounting to about 2,000 Giant Pangolins and 300 African Elephants.

“It was very devastating when we unpacked it. It’s like when you go to South Africa or even in Singapore, you hardly see pangolins. So where did these pangolins come from? It’s really heartbreaking,” said Dr Wong.

“After the big seizures, we saw the need to collaborate further internationally, and also through forensics to see how we can break the chain and help the source countries.”

Ms Xie Renhui, deputy director for international relations at NParks' Wildlife Trade Branch, added that she “didn’t expect there to be so much pangolin and ivory hidden at the back of the container”.

“We were unstuffing (the haul) and found pangolin (scales), then somebody shouted that there’s ivory tusks in the bag. Even now when I think about it, I still feel like … I don’t know where they found so many (animals),” she recounted.

"And I can’t understand why port operators at source countries can just turn a blind eye or just let things go through.”

Ultimately, the laboratory work done at CWF differs in magnitude from the work at the Centre for Animal and Veterinary Sciences, noted Dr Fernandez.

“What’s different here is that when you’re involved in something of this magnitude, and it’s direct (exposure), we’re not just sitting in the lab waiting. We’re all part of (a seizure); we all go down and experience it. It’s quite sobering,” she said.

“At first, it was very exciting, then it became very traumatic for all of us involved. You suddenly realise that so many animals are killed, but you don’t even understand what that looks like until it’s all laid out.”

The three major hauls in 2019 motivated Dr Fernandez’s team to “do the necessary to assist the enforcement from the laboratory side”. Previously, samples had to be sent to an overseas party and results could take months, she said.

For the average individual, a lack of knowledge about illegal wildlife trade shouldn’t impede one’s desire to help. Showing an interest in animals, “especially wildlife when they’re getting slaughtered by the millions”, is enough to start, added Dr Fernandez.

“This issue is something larger than yourself. I mean, how many of us will travel to Africa to work on something? But you don’t have to. That’s the point.”