IN FOCUS: No one wants to host the Commonwealth Games. 'Time to let it go', along with its colonial past?

Inclusive multi-sport meet or enduring relic of empire? CNA explores the Games' relevance to athletes and viewers, as well as what its reinvention could look like.

The Commonwealth Games has changed its name three times since it was first held in 1930. Out of 22 editions, the Games have been held in Asia twice – in Malaysia in 1998 and India in 2010. It has never been held in Africa. (Illustration: Rafa Estrada)

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

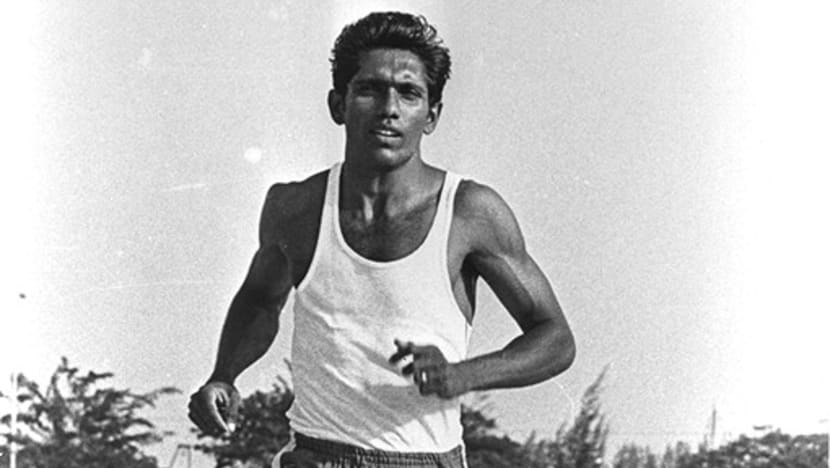

SINGAPORE: Former national sprinter C Kunalan, 81, has conflicted feelings about the Commonwealth Games.

The Singaporean track icon’s first shot at the quadrennial sporting event was in 1966, when it was still called the British Empire and Commonwealth Games.

Then 24 years old, his long journey to Jamaica culminated in his elimination in the first round.

“(But) the nice thing was wow, there were so many countries … I remember going down every day to the competition venue to watch everything,” he told CNA.

Mr Kunalan’s experience at the next edition in 1970 was more dramatic.

Already battling a heel injury in the lead-up, his Achilles tendon started to hurt upon arrival in Edinburgh. He eventually pulled a hamstring during his race.

One of his country’s most well-known athletes, Mr Kunalan represented Malaysia at the 1964 Tokyo Olympics, and post-independence Singapore at the 1968 Olympics in Mexico City. There, his time of 10.38 seconds in the 100m race became a national record that stood for 33 years.

Mr Kunalan also brought home multiple medals at the Asian Games and other regional meets before retiring in 1979.

While in his 20s, competing at the Commonwealth Games felt like a big deal, he said.

“But as time went on, I feel that it is no longer useful because there is enough competitions for all the countries to take part in,” he added.

“I don’t feel any sadness if it goes … I think it’s time to let it go.”

CENTARIAN ORIGINS

Critics have called the Commonwealth Games a colonial relic – and it’s not hard to see why.

The event is contested by athletes from the Commonwealth of Nations, which comprises mostly former British colonies among 56 member countries.

The organisation was first discussed in the 1880s, then officially created in the 1920s, said Dr Donna Brunero, who teaches imperial history at the National University of Singapore.

There are shared traits or traditions among Commonwealth nations that date back to their British colony days, including the Westminster system of government, she added.

And these include an interest in sports like netball, cricket and lawn bowls, which feature at the Commonwealth Games.

A regular sporting competition to demonstrate the unity of the British Empire was first proposed in 1891. There was an Inter-Empire Championships in 1911, but the idea didn’t fully crystallise until 1928. Then, a successful Olympics in Amsterdam inspired a Canadian journalist and athletics administrator to lobby for what would eventually become the inaugural British Empire Games in 1930.

This became the British Empire and Commonwealth Games from 1954 to 1966; the British Commonwealth Games from 1970 to 1974; and finally the Commonwealth Games from 1978.

The Games thus predates the likes of the Asian Games, first held in 1951, and the Southeast Asian (SEA) Games in 1959.

The current, modern incarnation of the Commonwealth of Nations was formally constituted in 1949, which established the member states as “free and equal”.

But Dr Elisa Prosperetti, an expert on decolonisation with Nanyang Technological University (NTU), described the Commonwealth as a stopgap measure to delay the decline of the British Empire, especially after World War II emptied its pockets.

It also started out as a hierarchical organisation where white dominions like Australia, Canada and New Zealand were historically seen as having more power and representation, she added.

Out of 22 editions, the Games have been held in Asia twice – in Malaysia in 1998 and India in 2010. It has never been held in Africa.

A country like Singapore has had a lot less to gain in the last 20 years from identifying itself with the Commonwealth, Dr Prosperetti continued.

It was perhaps more relevant when, for example, its Commonwealth MRT station opened in 1988 or when the Commonwealth Avenue road was built around 1963.

Dr Prosperetti also described the Commonwealth as reflecting the significance of the relationship between capital flows and the English language in global systems, for most of the second half of the 20th century.

But with the economic rise of China, the Middle East and Russia, trade and capital no longer flow through only English-speaking countries, she noted.

Now, the world no longer needs just English to access important institutions.

Queen Elizabeth’s death in 2022 also prompted reflections on the modern-day relevance of the British monarchy – ditto for associated bodies like the Commonwealth and its Games.

"We have other sporting events," said Dr Brunero. "Do we need to hang on to the Commonwealth Games?"

PASSED OVER

Arguments against the significance of the Games have intensified of late, sparked by the ongoing scramble to find a host country for the 2026 edition.

The Australian state of Victoria pulled out in July last year, citing projected cost overruns to A$7 billion (US$4.5 billion), more than double the original budget of A$2.6 billion. The Victorian Auditor-General's Office said in March however that the estimate was “overstated and not transparent”.

Then in December, Australia's Gold Coast withdrew a A$700 million joint bid with Perth, pointing to a lack of government backing.

Malaysia, which hosted the 1998 Games in Kuala Lumpur, also decided last month against stepping in as a replacement.

It said the £100 million in support offered to all potential hosts by the Commonwealth Games Federation would not cover the entire cost of organising a large-scale sports event.

The mere possibility sparked fierce debate – the president of Malaysia's Commonwealth Games Association called it a “once-in-a-lifetime opportunity" that could put the country back on the sporting map, but senior government officials deemed it “reckless”.

Singapore said shortly after that it had studied the feasibility of hosting the 2026 Games and decided not to bid for it.

Glasgow, which hosted the Games in 2014, could step in with a scaled-back version requiring "no significant ask of public funds", but with a programme reduced to 10 to 13 sports from the 20 held in Birmingham in 2022.

The following edition of the Games in 2030 is also at risk, with Canadian province Alberta withdrawing from hosting contention in August.

This limbo over finding a host country has launched debates on the costs and benefits of holding the Games. And on top of continued denunciation of its colonial links, there are some who simply see no need for a Commonwealth Games in what they perceive as an already stacked lineup of sporting events.

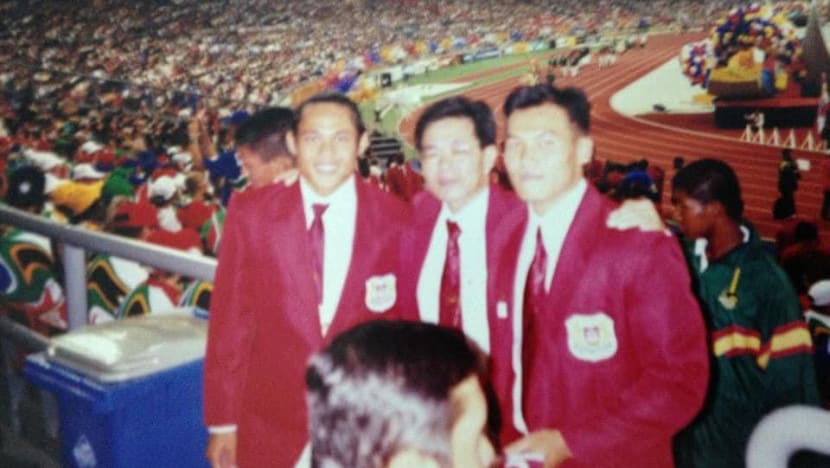

Former Singapore National Olympic Council (SNOC) vice-president Low Teo Ping, who was himself chef de mission for the 2014 Commonwealth Games in Glasgow, said the event was “neither here nor there”.

Like offerings for the region such as the SEA Games and Asian Games, other continents have their multi-sport equivalents such as the Pan American Games, Pacific Games, African Games and European Games.

And aside from these, athletes also participate in world, continental and regional championships for their respective sports.

Mr Low said the lack of an "emotive element” to the Commonwealth Games lends to its irrelevance. “When you don’t really feel like you’re part of the Commonwealth, it just doesn’t seem to be there.”

THE VIEW FROM THE GROUND

For Singaporean national swimmer Teong Tzen Wei, doing away with the Commonwealth Games “won’t have that big of an impact” because the Asian Games are held in the same year.

“Most of the time, the athletes would predominantly prioritise the Asian Games. I know of many people who would skip the Commonwealth Games to try and peak at the Asian Games,” he said.

But Teong, who won a silver medal in the 50m butterfly at Birmingham 2022, also acknowledged the high swimming standards at the Commonwealth Games, with powerhouse Australia often dominating.

“It’s a harder competition, and it puts a little bit more pressure to really try to do well and see where you can stand up against bigger competitors.”

This is also reflected in the prize money under SNOC's Major Games Award Programme.

An individual gold at the Commonwealth Games earns athletes S$40,000, while one at the SEA Games bags them S$10,000. They bring home S$200,000 for an Asiad win and S$1 million for Olympic gold.

Other athletes CNA spoke to were stronger advocates for the sporting relevance of the Commonwealth Games, with some calling it a mainstay in their calendars to commit to training for and competing at.

It's also particularly important to athletes whose sports do not feature at other major Games events.

For example, despite being a common co-curricular activity in schools, netball does not feature at the Olympics and the Asian Games; and is optional at the SEA Games.

Former national netballer Jean Ng pointed out that after qualifying for the 2006 Commonwealth Games, the next opportunity to represent Team Singapore at a multi-sport event was nine years later, at the 2015 SEA Games.

“It's an experience that we don't get very often,” she added.

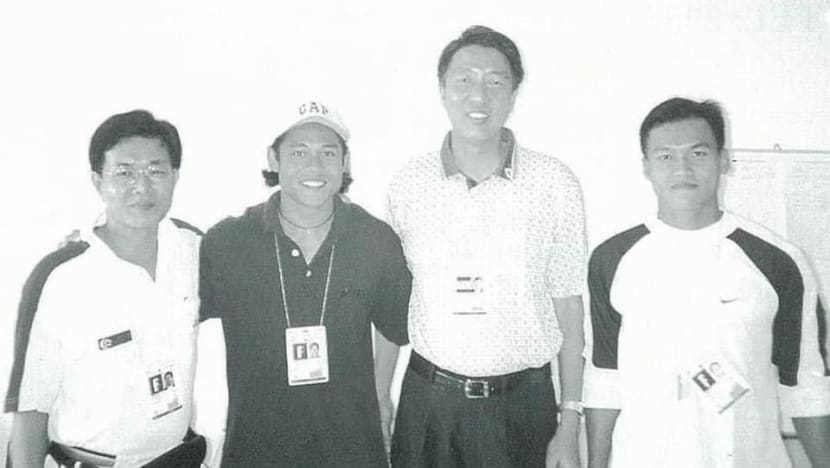

And for those who don't make it all the way to the Olympics, the Commonwealth Games makes the cut as another major meet to aim for, said former national sprinter Hamkah Afik.

The 52-year-old, currently a coach, competed in the 100m and 200m races at the 1998 Commonwealth Games in Malaysia. He still holds fond memories of how packed the Bukit Jalil National Stadium in Kuala Lumpur was then.

“How can it be that this is not important or not significant anymore, when all this while ... people look forward to it?” he asked.

One such person is 35-year-old sports fan Wong Chun Meng, who makes time to catch live telecasts of athletics, swimming and table tennis at major Games.

He recalled watching the 2002 Commonwealth Games on TV as a teenager, and has tuned in to most broadcasts since.

Among his fondest memories are of Singapore's only Olympic champion, the recently retired Joseph Schooling, win a silver medal in the 100m butterfly at the 2014 edition in Glasgow. Most recently in 2022, he witnessed badminton pair Terry Hee and Jessica Tan battling to a historic gold medal in the mixed doubles.

These multi-sport events are an opportunity to watch local athletes rub shoulders with top athletes from around the world and see how they match up, Mr Wong added.

“At least seeing them hold their own, I think there’s a sense of pride in that. That we Singaporeans can also make it at that kind of level.”

"ABLE TO REINVENT ITSELF"?

Even if the Games overcomes its imminent challenges, experts CNA spoke to agreed the event is in dire need of an overhaul.

In November, Commonwealth Games Federation president Chris Jenkins announced intent to remodel the meet for “a more sustainable future”.

The objective is to attract host cities by not only reducing costs but also exploring how to raise returns to governments “so they’re getting much more out of hosting the Games”, he said then.

Former Singapore Sports Hub chief executive officer and ex-national swimmer Oon Jin Teik pointed out that the federation has bandied about terms like “innovative new concepts".

A remodelling of the Games could include having each country host a different sport, Mr Oon suggested. And helping athletes from Commonwealth member nations reach a certain level could also lead to more relevance and interest.

For example, the federation could institute a scheme where the 10 most advanced countries provide support to the 10 least advanced countries in the Commonwealth to help athletes train and prepare for the Games, he added.

“It’s easy to attack the Commonwealth because it ultimately stems from the countries who were part of the British Empire, but it's been quite resilient. It's been able to reinvent itself,” said Associate Professor Kevin Blackburn, a sports history expert with NTU.

For one, the Commonwealth Games is more inclusive than the Olympics, with non-disabled athletes and para athletes competing under the same umbrella, in the same arena and at the same time, he noted.

At the Commonwealth Games, athletes with a disability have been included as full members of their national teams since 2002, and they attend ceremonies as one contingent.

“I often think, why aren't the SEA Games and the Asian Games doing the same thing? Because you're sending out a message that there's the 'real' Games and then there's other Games that are somehow not real (and) just for all the people who are disabled,” said Assoc Prof Blackburn.

NUS’ Dr Brunero described it as a “conscious recasting” of the Commonwealth and the types of messages it wants to emphasise, with one of them being inclusivity.

The organisation is “quite aware” of its long history, she said, adding that there is still "value" in what its modern incarnation – which is not focused on British Empire origins – does for small states and in advocating for environmental and human rights.

NTU's Dr Prosperetti said it could be argued that the Commonwealth Games has more staying power than its other initiatives such as the Commonwealth Prime Ministers' meetings, due to sports being a "phenomenally sticky" and enduring legacy of empires.

If the Games can find a way to acknowledge the complexity of the history that produced it, such as by taking on an educational slant, it would carry even more meaning and relevance that other organisations in the Commonwealth don't have, she said.

The current name of the Games, its history and the context it was used in is problematic, she added.

"If they want to survive, to justly be an institution that acknowledges a complicated global history, I think it makes sense to rename it."

But all this will be difficult without political will.

And in any case, cancelling the Commonwealth Games and even the Commonwealth itself could utlimately be detrimental in other ways, the historian added.

“It's problematic to say 'colonial history was bad, and therefore we erased it'," she said. "Because then you erase also a tremendous swath of human experience.”