A land bridge too far? Thailand's revived Kra megaproject a divisive issue among local residents

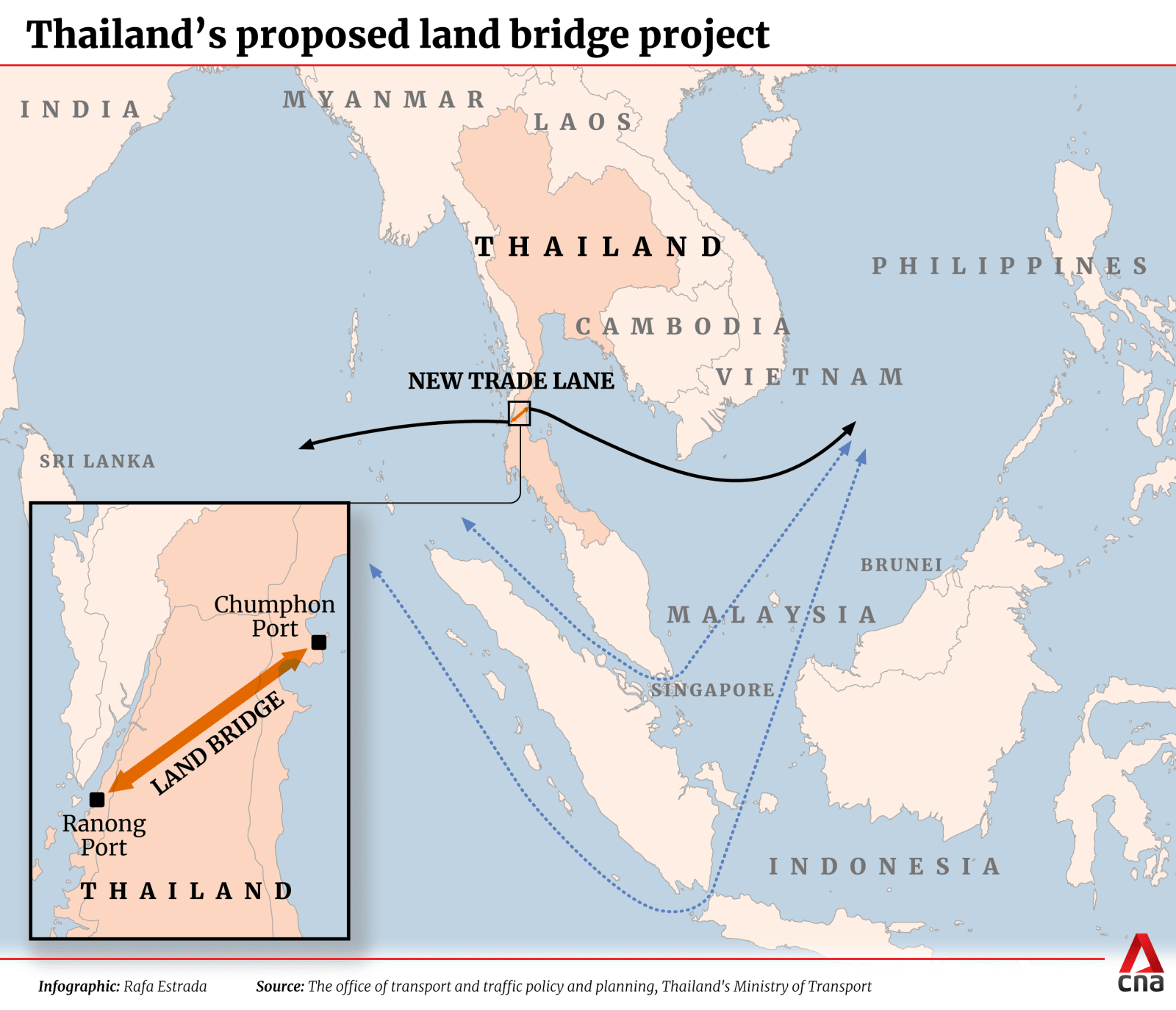

The ambitious plan in Thailand's southern region could see shipping trade bypass Singapore and Malaysia. While it's been redesigned to keep the mainland intact, the project is threatening to split local communities apart.

RANONG, Thailand: As the Thai prime minister took a tour through the southern province of Ranong in January, a woman wearing a headscarf emerged from the crowd and clung to his arm, pleading for his attention, camera shutters clicking from a sizeable media contingent watching the encounter.

“Please help me. The land bridge project will dig a deep sea port here. It’s right at my home. That’s my livelihood,” she said. “Can you delay the project, please?”

The woman’s name is Thom Sinsuwan. For three decades, the 64-year-old has lived in and among the mangrove forest that lines the shore of the Ranong coastline.

Her community of small-scale fisherfolk is now seemingly on the precipice of major upheaval.

Ms Thom’s plea to the prime minister, Mr Srettha Thavisin, was a cry for attention, symbolic of many locals across two provinces dazed by the prospect of a megaproject on their doorsteps.

Since being sworn into power in August last year, Mr Srettha has been on a roadshow of sorts, pushing his ambitious plan to develop a land bridge project that would connect the Andaman Sea with the Thai Gulf.

The aim is to create a new international trade route, avoiding the congested Malacca Straits between Indonesia and Malaysia and shortening travel time for vessels.

It has the potential to draw ships away from Singapore and Acting Transport Minister Chee Hong Tat told parliament that the Port of Singapore would need to make sure it remains “competitive and relevant”.

Two deep sea ports would be built in Ranong and Chumphon provinces and be linked by 90km of highways, railways and pipelines across the Kra Isthmus - the narrowest section of the Malay peninsula.

From the secluded Andaman islands, mangrove forests and urban ports of Ranong, to the mountainous farmland nestled alongside national parkland, and to the sleepy fishing flats and coconut groves on the Thai Gulf, communities face uncertainty about the changes that could impact their livelihoods and environment.

Some say they support the project and the transformational potential it could have in a part of Thailand long considered an economic backwater. But others are fiercely against it.

Since the 17th century, various leaders have investigated the possibility of excavating a canal that would split Thailand in two.

The Suez and Panama canals have provided the world’s shipping industry with major navigational shortcuts and economic windfalls and Thailand has long wanted to provide a new trade route between the Indian and Pacific Oceans.

The grand ambition of the US$36 billion land bridge is to slash six to nine days off ship journeys that otherwise go via the busy Malacca Strait. The first phase of the land bridge project could be finished by 2030, with the final completion targeted in 2039.

The economic viability of the project has yet to be proven and no major investors have been identified.

As momentum builds, however, the project that has been redesigned to keep Thailand’s mainland intact is threatening to split local communities apart instead.

A DEEP SEA PORT ON THE ANDAMAN

After a smooth boat ride through the maze-like wetlands on the flank of the Ranong Biosphere Reserve, eventually a narrow inlet meets the open sea in a broad bay, wide and bright.

This is the journey that Ms Thom makes every day, along with dozens of others from the fishing hamlet in Ratchakrut sub-district.

As well as casting their lines and nets, they have established small fish farms in the brackish waters, and catch crabs and other shellfish in the muddy cove.

These fishing grounds lie close to Ao Ang Bay, the site of a proposed deep sea port and massive land reclamation project. Within a few years, a vast amount of the world’s shipping trade from the Middle East, India and Europe to East Asia could pass through here.

Ms Thom is defiant and says she wants to die on this land, by this sea, undisturbed by an industrial wave on the horizon.

“I am scared of the land bridge project. I know that our home will be impacted, we will lose the place where we make a living and we don’t know where to go because there’s no place for us,” she said. “Deep down inside, I will definitely not leave. I feel so uneasy. I eat tears every day.”

During Mr Srettha’s visit, the community submitted a petition to voice their opposition to the land bridge. But these 17 households in the village are unlikely to be the reason the project does not go ahead.

The small-scale fisherfolk have fewer rights than other Thais. They are considered displaced and hold no official national identification cards. Their ability to have jobs or own land is tenuous at best.

It means that both their ability to gain employment in new industries in Ranong - or gain proper compensation for a loss of their homes - is unclear, a fact that fuels their opposition.

There is more at stake than local livelihoods here.

The Ranong Biosphere Reserve covers 30,000 hectares, comprising mangrove forests, waterways and marine area. It was recognised and listed for protection by UNESCO in 1997, is home to unique fauna and flora and is an important carbon sink.

It also abuts the prospective zone for the development of Ranong’s deep sea port.

“The development will not affect the area a lot because the reserve itself has been designated as a permanent preservation area,” said Khayai Thongnunui, the director of Ranong Mangrove Management with the Department of Marine and Coastal Resources.

“There’s always a law in place that stipulates preventive measures to prevent impacts from happening,” he said.

Other experts are not so optimistic.

Mr Sakanan Plathong, a marine expert from Songkla University told local media outlet ThaiPBS in November last year that land reclamation adjacent to the protected area could block the breeding routes of many aquatic animals, cause heavy metals to enter the marine area, disrupt sediment and hamper the local fishing industry.

While an environmental study will reportedly examine the impacts of the project within a five km radius, he urged authorities to expand that area further. An oil spill in the area could have long-lasting impacts on the wider environment, he noted.

After being requested by a government committee to act as an environmental impact consultant with the project, Mr Sakhanan said he was unable to be interviewed by CNA.

BUSINESSES BUZZING FOR INVESTMENT

Despite the concerns, a wider effort led by Mr Srettha is underway to lure investors to the region. And he already has keen supporters in Ranong.

About 45km north of Ao Ang Bay, Ranong town is a melting pot of Thai and Burmese culture. A noisy and colourful port is a scene of cross-border trade with southern Myanmar and a busy hub for the seafood industry.

The province has suffered from a lack of investment in recent decades. Old industries like forestry and mining have been phased out and tourism has been vastly outstripped by nearby southern hotspots like Phuket and Krabi.

Ranong had the eighth-lowest gross provincial product (GPP) output in the entire country in 2021. It also was in the top 10 for provinces with the highest poverty levels in 2022, according to the Office of the National Economic and Social Development Council.

The business community is hungry to see investments flowing in on the back of the land bridge, which is set up to be a joint venture between the public and private sectors.

“I personally agree with it because we’ve had so many industries and they are gone. Now we have tourism. If the land bridge project comes, it can develop tourism in many aspects,” said Mr Somchai Uitekkeng, the president of Ranong Tourism Association.

He said he is confident that foreign investors are ready to open their wallets to develop Ranong, including for pier infrastructure that could welcome cruise ships as well as hotels and modern medical facilities that are currently lacking.

Local businesspeople are ready to spend too, he argued; but they have lacked opportunities to do so, given the low visitor numbers and limited returns on investment.

Improved connectivity to the region for trade and tourism could change that equation.

“If we have an airport with more airlines, such as having flights from Phuket or Hat Yai to Ranong, tourists from Singapore and Malaysia will be ready to come,” he said. “The current situation now is about clarity. I think some people still don’t understand the project”.

The province’s Chamber of Commerce is also on board, eyeing the wider development that could stimulate the local business community, especially in the halal food industry and around wellness tourism. Southern Thailand products could be exported out of the Ranong port instead of having to be transported to Penang in Malaysia and seafood could be processed locally instead of being shipped to other parts of the country.

“Ranong province’s economy will change, the GPP will soar, and trading will leap forward,” said president Mr Pornsak Kaewthavorn.

“We have thought about it and we want it. We want to see change in the province,” he said.

From the offices in town to the beaches of Koh Chang, a picturesque island dominated by rubber farming and some seasonal escapist tourism, that sentiment is the same.

For Ms Suchada Ruangroj, development brings with it some hope that decades of economic inertia might be done with.

The deputy chief of Koh Chang village and owner of Eden Cafe Bistro says that “time has stood still” for 30 years on the island, which is less than one hour by boat from the mainland.

Villagers are “drowning in debt”, she said, due to low rubber prices and tourism that has not advanced in years. The island has poor roads, a lack of basic infrastructure and does not even have electricity, relying on diesel generators for power.

“We are stuck in this same place and at the same pace. It’s a struggle. Maybe this project can make things better for us,” she said.

While the land bridge project will not directly impact Koh Chang and the surrounding islands, secondary factors like sedimentation for dredging and pollution from the port could arise.

The view at sunset here is a stunning one - an unbroken vista into the shining Andaman. Soon, cargo ships could join the picture.

Still, Ms Suchada is unperturbed about the prospect of a paradise-breaking megaproject.

“It will be such a pity to lose this stunning view,” she said, “but if the project can help and benefit the whole country, then there won’t be much problem for us to sacrifice this.”

DURIANS AND DIVISION

The road from Ranong to the rural district of Phato in Chumphon is both winding and dramatic. Past the Khlong Phrao National Park, it bypasses precious forest and an abundance of waterways.

Further along, mature durian plantations line the hills and fruit trees the lower valleys.

Constructing major transport infrastructure through this area looms as a time and energy-sapping endeavour for the land bridge’s masterminds. 21km of tunnels are included in the project plan.

And they will have local opposition groups impeding their progress too, newly formed and energised by the revitalised nature of the project.

Dotted sporadically on the roadside are the literal signs that a community is united in resistance. “No Land Bridge” is that clear message.

At a local cafe, members of the Love Phato Network are hearing the latest developments and devising new messaging and strategies to combat the land bridge, which they understand will be constructed directly through their land.

“This project doesn’t meet the needs that the local people have. It doesn't benefit the local people, rather, it will completely destroy the jobs of the local people,” said Mr Somchok Jungjaturunt, a member of the network and local fruit grower.

The promise of some 280,000 new jobs has been circulated by the Office of Transport and Traffic Policy and Planning - the agency conducting the project’s feasibility study - as a key local benefit of the land bridge. But there is deep suspicion in Phato that those numbers are “just a fantasy”, according to Mr Somchok.

He said local people who already operate their own businesses will refuse to become employees in factories in an industrial town, should it be built in the area.

“Our incomes are stable. The government can’t make an excuse to improve our lives by creating a megaproject. The development can come in different forms. It doesn’t need to come from industrial cities,” he said.

“In effect, they are chasing people out of homes.”

Murmurings about rampant land speculation, buying large areas cheaply with the aim to sell at a profit later when value rises, are loud in the community. Many are adamant that political figures are behind the push to purchase land around the project.

In this mostly ageing community of lifelong farmers, the prospect of selling up and moving remains a hard sell.

Further east, the terrain flattens and falls away to the straw sands of the Thai Gulf, the finish line of the land bridge, where shipping containers would be processed onto waiting ships bound for China or Japan.

For now, small resorts, seafood restaurants and aquaculture farms line the coast at Lang Suan in Chumphon.

Development has been lethargic here and life moves accordingly for those who call it home.

Little reliable information has been disseminated to the community here. The same whispers about aggressive land buying persist. But in the eyes of some, with progress comes sparks of opportunity.

Mr Perawat Thiparat, a local restaurant owner, says he thinks increased economic activity will naturally draw more people to the area, and to his family’s resort.

“When I heard about the project, I thought it might be good for the economy and there would be development, but I don’t know what impacts it will make,” he said, while fishing off a pier at sunset.

On the very same pier, Sureephon Sophonmanee thinks she might be the sole opposing voice in the area. The 57-year-old still plies the seas in a small fishing boat to make a living.

For her, simply not being a financial “burden” to her children is enough reason to exercise caution about such a major environmental intervention. She says the government has not mentioned any compensation they would receive for their livelihoods being affected.

“What if they do the project and it isn’t worth it and it becomes deserted? We cannot get the sea back,” she said.

“There has to be development here and support from the government but it should not be a megaproject that causes destruction.”

Additional reporting by Ryn Jirenuwat.