From secondhand books to curry puffs, can Singapore’s heritage businesses survive the next generation?

Heritage businesses in Singapore have had mixed fortunes. Some, by innovating and adapting to evolving consumer tastes, have managed to continue thriving, but others in sunset industries can only do so much to stay relevant.

Support schemes from the government only go so far in preserving heritage enterprises as they face a variety of hurdles, including a lack of succession plans. (Illustration: CNA/Nurjannah Suhaimi)

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

You would be hard pressed to find a shop in Singapore that does not accept cashless payment or have an online presence, least of all in the upscale shopping belt that is Orchard Road.

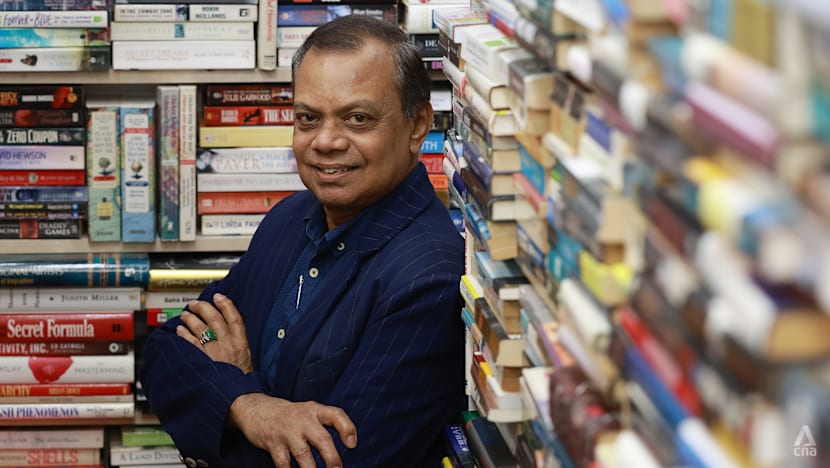

Yet, in these respects and more, the 34-year-old ANA Book Store at Far East Plaza remains defiantly old school.

Its founder and owner, Mr Noorul Islam, even records all sales in a ledger book for accounting purposes.

"I'm a simple, old man," the 72-year-old said, when asked why he keeps it all analog.

What is most old school about ANA Book Store, however, is the nature of its business.

In an era of shortening attention spans and a preference for online content, Mr Islam sells secondhand books – just as he has done since inheriting the shop from his parents in 1992.

Though he has a regular stream of customers and makes "enough" sales, he candidly acknowledged that the days of ANA Book Store are numbered, because no family member intends to take over from him when he finally retires.

"They all have good jobs and careers; nobody wants to take over the shop," he said. "As long as my legs, hands can move, I will keep the shop open."

Over at Peninsula Plaza along North Bridge Road, about a 10-minute drive from ANA Book Store, is Cathay Photo, now run by the third generation of the founder's family.

Long known as a purveyor of professional photography equipment since 1959, the Cathay Photo of today is active on social media, has a strong e-commerce presence and is extending its reach beyond camera aficionados.

Recently, the shop found itself having to manage a two-hour-long queue comprising youngsters eager to buy what was trending on social media: the Kodak Charmeras – tiny toy cameras selling for under S$100.

They are a sharp contrast to the high-end products that remain the outlet's bread and butter.

Mr Ryan Toh, who helms the business with his cousins Jill Koh and Charmaine Toh, said of the young buyers: "Many of them exclaimed that they had never been to this part of Peninsula Plaza before. They didn't know that such a nice, professional camera shop existed.

"So that was our chance to get to know more customers."

He added: "Our staff members offered the same level of customer service to them as they would with regular customers buying expensive equipment, because this is our first interaction with them.

"So if it is positive, then next time, these young customers will think of us and come back to us."

Such are the mixed fortunes of the nation's heritage businesses, which have endured for decades despite changing consumer tastes and economic pressures.

Ranging from textiles to foods, these homegrown businesses have garnered renewed attention in recent years as efforts are made to preserve them.

One initiative is the SG Heritage Business Scheme, which was introduced last year by the National Heritage Board (NHB). Cathay Photo and ANA Book Store were among the 42 businesses in the pilot scheme.

Other schemes include the Organisational Transformation Grant, also by NHB. Introduced in 2021, it offers up to S$40,000 of funding for heritage businesses that want to adopt transformative projects that will help them be more sustainable in the long term.

Heritage experts said that preserving heritage businesses is important because it allows the society of today to experience and live a part of Singapore's history, as opposed to just reading about them in books or observing artefacts.

Associate Professor Ho Kong Chong, emeritus professor of sociology and anthropology from the National University of Singapore (NUS), said that people may not visit a heritage building all the time.

"But we eat all the time, and we can eat at a heritage food business on a regular basis. And each time we patronise such a heritage business, it is a reminder of who we are, it's a reminder that Singapore has these businesses with long lines of history that stretch back 50, 60 over years."

Although support schemes are helpful, they can only go so far in preserving heritage enterprises, experts and business owners themselves said.

As businesses, they have similar concerns that other enterprises here face, such as rising operational costs and manpower shortages.

Then, with the heritage component, they must also grapple with added challenges, such as balancing authenticity with evolving consumer tastes and finding successors keen to take over a traditional business.

The extent of these challenges can also be a matter of luck – whether the business that is inherited happens to be in an industry that is still chic or a sunset one.

HERITAGE VS RELEVANCE

Like most enterprises, heritage businesses must deal with the perennial pressure of rising operational costs.

Beyond material and manpower expenses, rental costs are especially critical since many are located in prime central locations.

CNA reported earlier this month that rental rates in the historic Kampong Glam area have surged significantly – in some cases doubled – driving out small businesses, while larger brands and tourist-oriented businesses with deeper pockets swoop in to take their places.

Rising rents are not limited to just Kampung Glam, business owners said.

Mr Ng Tze Yong, a sixth-generation artisan at Say Tian Hng Buddha Shop in Tanjong Pagar, told CNA TODAY that his grandfather had fortunately decided to "bite the bullet" some 40 years ago and buy the unit where their shop is now located.

"Since then, rents have risen. On our street, many of the businesses come and go because they cannot keep up," Mr Ng added.

"If we had to pay rent, we may not survive. Or at best, we will probably have to relocate to an industrial area, and then heritage becomes invisible because those are not places where people walk past and discover things."

Evolving consumer taste is another major challenge.

Heritage educator Ho Yong Min, founder of The Urbanist Singapore, a content platform dedicated to heritage storytelling and urban design, said: "People love heritage in principle, but day-to-day spending is shaped by convenience and platforms.

"Long-time department stores like John Little (founded in 1842) had to go because people now have more choice and convenience when it comes to online shopping."

In Singapore's context, the shift in consumer preferences away from heritage brands can also be attributed in part to the evolving composition of the society, one academic said.

Associate Professor Lau Kong Cheen, who heads the marketing programme at the Singapore University of Social Sciences (SUSS) school of business, said that the nation's heritage brands may not resonate with immigrants who come from a different background.

"For example, if you look at traditional designs of batik and kebaya offered by Toko Aljunied, the style and designs may not resonate with many of our new immigrants unless their background is from Indonesia or Malaysia," he added. Toko Aljunied is a heritage business along Arab Street.

All businesses have to keep products relevant to consumer demand, but it is more acute among heritage businesses since they need to balance innovation with authenticity.

The authenticity of the heritage business relates to the product or services sold, the processes or materials used in producing them, as well as customer experience.

"Once the brand loses its authenticity, it loses its identity as a heritage brand, which is the soul of the business," Assoc Prof Lau said.

"(But) if the brand loses relevance, this will sacrifice its existence," he added. "New and existing customers will not gravitate to it and the business will collapse."

Succession and the transfer of the traditional skills associated with the trade are the other unique challenges that heritage businesses face.

Mr Ho the heritage educator said: "When the craft lives in one or two people, retirement is not just a staffing issue – it can be the end of the heritage.

"We see that a lot in smaller heritage food and hawker stalls."

Such is the predicament for Mr R Jayaselvam, a traditional flower garland maker who opened Anushia Flower Shop in Little India in 1994.

His two sons, aged 30 and 27, help out at the shop during festive seasons and with online marketing efforts, but they are not interested in learning the traditional craft and do not intend to inherit the business.

"It's very manual work," the 61-year-old said of his craft trade, adding that his children have well-paying jobs.

Mr Jayaselvam conducts hands-on cultural exposure workshops for tourists and Singaporeans, but the short sessions are only meant to raise awareness and appreciation and do not suffice to meaningfully pass on the craft.

"After the course, 100 per cent nobody ever comes back (to learn more)," he said.

KEEPING THE HERITAGE ALIVE

The Singapore Heritage Business pilot offers support for eligible domestic brands in several ways, such as an SG Heritage Business mark on storefronts for ease of identification, inclusion in a directory on NHB's heritage portal and business consultancy services.

Businesses and experts alike agreed that the scheme is a good start because it draws attention to heritage businesses.

Mr Islam of ANA Book Store said that over the years, he has relied only on word-of-mouth to promote his business. Most of his customers are returning regulars, while the remainder are shoppers at Far East Plaza who stumble upon his store, or tourists putting up at nearby hotels who are told about the bookstore by hotel employees.

"This (NHB) scheme is good for old business owners who run their shops alone and don't do marketing," he added.

Mr Ho from the Urbanist said that the scheme can raise awareness, but it cannot, on its own, "fix structural realities like manpower, rent volatility or changing market preferences".

"The scheme will work best if it drives sustained demand and helps owners make changes that protect the living core (of the heritage business)."

The living core, Mr Ho said, refers to the part of the heritage business that cannot be replaced once it is gone.

On their part, businesses that have survived through the decades have been making various efforts to thrive such as by diversifying their offerings, taking on novel marketing strategies or offering their products in different ways.

BROADENING BUSINESS APPEAL

Associate Professor Ho from NUS pointed to Old Chang Kee, one of the enterprises recognised under the NHB's pilot scheme, as a business that has managed to keep up with the times while staying true to its heritage.

He noted how Old Chang Kee has expanded the variety of food that it sells, such that it appeals to a broad base of customers, while still selling the curry puffs that are synonymous with the brand.

"They continue to deal with a signature heritage item, so who's to begrudge them for making business sense and selling a greater variety of products?

"If, for example, they start operating a cinema, then that's really totally out of it. But they're still in the food business, and they're still selling their signature product … From both a consumer as well as the academic point of view, I think that's okay in terms of maintaining the heritage."

Heritage businesses can also engage in branding and marketing strategies that can help shed their "dated" image in the eyes of younger consumers.

Dr Lau of SUSS highlighted a joint marketing campaign between sports brand Adidas and traditional toast chain Ya Kun Kaya for National Day in 2024. Through the collaboration, the companies released limited edition apparel featuring motifs of Ya Kun food items.

"This made Ya Kun's image more contemporary and drew the attention of the younger generation. And this by no means diluted the (Ya Kun) brand," he said.

"Co-branding with a popular or young brand can reignite interest and provide an avenue for younger customers to find appeal towards the brand."

EXPANDING SERVICES

Other heritage companies have turned to modern business models to stay relevant.

Rumah Makan Minang, a long-standing nasi padang business with its main outlet along Kandahar Street, invested in a centralised kitchen in 2012.

Its managing director Hazmi Zin, 43, said: "When I started taking a more active role in the business, I wanted to grow it to a bigger scale because I feel it would make it more sustainable."

Mr Hazmi and his three younger siblings are now the third generation running the family business, which was founded by his grandmother.

He recalled how the sole outlet was severely affected when the Kampong Glam area underwent major redevelopment works in 2011 that lasted about a year.

During that time, business declined as the area around his eatery was boarded up, and many customers were reluctant to patronise it due to the noisy environment.

The setting up of a centralised kitchen allowed Rumah Makan Minang to expand into catering services and open up two new branches in Tampines and Jurong West, instead of relying on just the main outlet for its revenue.

He said that there was some initial resistance from some of his older family members. They were not only worried about the costs involved, but also the move from traditional manual methods of cooking to partially automated ones in the central kitchen.

"We went through a lot of research and development, made some fine adjustments to the recipes and successfully retained the same taste as when we cooked the dishes ourselves in the Kandahar Street kitchen. That, in itself, is already maintaining the heritage," Mr Hazmi said.

He acknowledged that when it comes to handing over food businesses to the next generation, there is always a risk of a slight change in taste or quality when the younger family members take over the cooking.

However, he felt that so far, that has not happened with Rumah Makan Minang.

"With automation, as long as we stick to the ingredients and the procedures that we have established, anybody can cook it. And we will still maintain the same taste and quality."

At Say Tian Hng Buddha Shop, where the main business is the handcrafting of Buddhist and Taoist deity statues, it has to compete with mass market, machine-made statues sold at lower prices.

Instead of seeing it as a direct threat, the family has turned it into an opportunity, since the cheaper, mass-produced idols cannot be returned to the factories for any restoration work should they get damaged.

Restoration works for such statues now make up about half of its business, while handcrafting commissioned work accounts for the other half.

Mr Ng said that after the shop revamped its website about three years ago, it began receiving orders from overseas as well, as far as the United States, Europe and South America, from devotees or collectors who appreciate craftsmanship.

"It's a small trickle, just a handful, but it's still interesting and has potential," he said, adding that this would open up his business to a potential market "multiple fold" in size compared to its current core customers of households and temples in Singapore.

BUILDING RELATIONSHIPS

For businesses that are handed down across generations, maintaining relationships and building upon them is yet another way to keep the legacy alive.

At Cathay Photo, the third-generation owners do this by continuing the spirit of giving, which their grandfather and shop founder Toh Mun Peng had initiated by granting bursaries and scholarships to a few tertiary students in Singapore every year.

It started with students from Nanyang Technological University in 2011, and later on with the Lasalle College of the Arts.

Cathay Photo also organises workshops and puts out educational content across its social media channels.

"All these are our ways to support the education of the next generation of photographers and photography enthusiasts out there," Ms Charmaine Toh said. "It is the building of a long-term relationship."

WHEN HERITAGE MEETS THE SUNSET

In the old days, the Kampong Glam area was the hub for Muslim pilgrims from neighbouring countries to gather, before boarding ships to Mecca in Saudi Arabia to perform their haj, a sacred obligation for able Muslims who have the means to go on this pilgrimage.

Fittingly, Halijah Travels, also recognised under the SG Heritage Business Scheme, is located in the heritage area today in a conserved shophouse.

However, its general manager Haffidz Abdul Hamid observed that things are vastly different today, with the pilgrimage and travel industry here slowly but surely shrinking.

The Malay-language weekly Berita Minggu reported in February last year that more Singaporeans are going to Malaysian travel agencies for umrah (minor pilgrimage) packages because they are cheaper.

In December, the newspaper also reported that Singapore's travel agencies are finding ways to deal with the rising trend of pilgrims undertaking the umrah independently, instead of booking a package with a travel agency.

To partly deal with this situation, Halijah Travels offers free pilgrimage preparatory courses even to do-it-yourself pilgrims who do not sign up with the agency.

"We also see it as a form of religious service to the community," Mr Haffidz said. "At the same time, these DIY pilgrims will get to know us and if in the future they would like to do another trip, they may consider going with us."

Bookings for haj and umrah continue to be his agency's core business, but non-religious guided tours now account for 30 per cent of its volume.

However, even such a diversification strategy has done little to shield the firm from the broader trend of Singaporeans going on overseas holidays without engaging a travel agency.

"Travel agencies are a dying industry," Mr Haffidz said.

Haj pilgrims are still required to book their pilgrimage through authorised agencies, making his business still relevant – at least for the foreseeable future. But beyond this, Mr Haffidz harbours no hope of seeing his family business expand any further.

Heritage businesses teach us how Singapore became Singapore … If they fade, our heritage becomes something we consume as stories instead of something still practised in the present. That'll be such a pity.

Similarly, Mr Jayaselvam from Anushia Flower Shop has embraced change to stay relevant, but there is a limit to how much his business can expand with him as its sole worker.

In 2019, he built an e-commerce website for his flower garland shop, which turned out to be a lifeline because it allowed him to continue taking and fulfilling orders during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The website and social media pages have also led to an increase in orders for elaborate wedding garlands – from two to three a month to about a dozen now.

However, this is as far as he can scale up.

"I only have two hands," Mr Jayaselvam said, adding that the process cannot be automated and the garlands cannot be made in advance because they are made with fresh flowers.

GOVERNMENT SUPPORT FOR HERITAGE BUSINESSES

Throughout this year, the National Heritage Board (NHB) is expected to roll out these initiatives under the pilot run of the SG Heritage Business scheme:

- First quarter of 2026: NHB will kick off a marketing campaign spotlighting the legacy and community impact of each of the 42 businesses

- By June 2026: An online register of the heritage businesses will be launched, to make it easier for local and international visitors to find and support them

- From March 2026: Tailored consultancy support will be rolled out to address common "last-mile gaps" the businesses have shared with NHB

"NHB will engage each business further to understand their practices and processes, identify key gaps and opportunities, and work with consultants to develop practical and business-appropriate solutions," said an NHB spokesperson.

"Where relevant, businesses may choose to tap on available grants offered by NHB or other agencies to support implementation."

For example, Enterprise Singapore offers the Productivity Solutions Grant and the Enterprise Development Grant which provides up to 50 per cent in fundings for small and medium enterprises looking to improve their productivity or explore new growth areas and markets.

Prior to the SG Heritage Business Scheme, NHB launched the Organisational Transformation Grant in 2021 that supports transformative projects to help heritage businesses be more sustainable in the long term.

Over 55 projects have been supported to date, said NHB.

The NHB spokesperson added: "As part of the Inter-Agency Taskforce for Heritage Businesses, Traditional Activities and Cultural Life, NHB works with other agencies to better understand these challenges and align support across government, and will provide updates when ready."

The taskforce was formed in February 2025.

SURVIVING IN A BUSINESS JUNGLE

At the end of the day, these heritage businesses are still for-profit entities, and the owners know that the onus is on them to ensure their own survival.

Mr Ng from Say Tian Hng Buddha Shop said: "Businesses survive by the laws of the jungle. Being a heritage business doesn't exempt us from that."

The government can offer support to preserve heritage, but business owners cannot start thinking like charities because they would not be putting their “whole focus to solve the real business problems", Mr Ng added.

At the same time, if Singaporeans truly find it important to preserve the country’s heritage, they should show meaningful support for these businesses as well.

"A lot of us look at heritage through a romantic, nostalgic lens. But I think the uncomfortable truth is that we also need to put the money where our mouth is," Mr Ng continued.

"For example, when you're in the office and you're tasked to buy refreshments for a big meeting, would you just order from the most convenient coffee chain, or would you make the extra effort of supporting a traditional bakery?"

Mr Ho of The Urbanist said that the closure of a heritage business is not the mere loss of nostalgia or "old brand", but also living knowledge of things such as recipes and craft skills that are not readily available in textbooks.

"Once the last practitioner closes shop, you cannot simply or easily recreate it with a grant or museum display," he pointed out.

"More significantly to me, these heritage businesses teach us how Singapore became Singapore, through trade, grit, daily life and relationships in ways people can see, taste or feel.

"If they fade, our heritage becomes something we consume as stories instead of something still practised in the present. That'll be such a pity."

A pity, but an inevitable reality for some.

Caught between the declining demand, the spectre of rising rental rates, a lack of successors, and no clear vision for a pivot, Mr Jayaselvam, for one, is resigned to the idea that Anushia Flower Shop will not survive him.

"Running a heritage business in a sunset industry is as if I have one foot in my business, one foot in the crematorium," he said.

"But it's okay, this was the destiny that I picked when I started this business."