'Finally, someone's interested in you': When male victims of sexual crimes are mocked or dismissed, the hurt deepens

The jocular and trivialising comments that people often make at the expense of male victims of sexual crimes reflect mindsets rooted in toxic masculinity and gender norms, experts say.

Experts said that trivialisation or dismissive responses to male victims of sexual crimes can have an impact on them that is as profound as the assault itself. (Illustration: CNA/Nurjannah Suhaimi)

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

The MRT train on the East-West Line was mostly empty that day in 2017.

Yet, a woman in her 30s chose to stand uncomfortably close to 22-year-old Mike (not his real name), who was leaning against a glass panel.

"She had places to stand, places to sit, but she chose to stand next to me," he recalled.

He brushed it off at first, but as the train trudged along, he felt the woman's hand touch his thigh. He turned his head to see that the woman had angled her arm backwards in an unnatural position to do so.

"At that moment, I was just baffled. My mind went blank and I couldn't think. What am I supposed to do in this kind of situation? Who's going to help a guy like me?" he said.

"Because of that, I didn't react in any way. I just cowered in the corner as much as possible and I realised that the more I did that, the bolder she got."

The woman retracted her hand from his thigh only when they reached a station where the train doors opened next to them and other passengers streamed in.

Mike took the opportunity to leave the train then.

When he confided to his friends about what had happened to him, their responses, regardless of gender, were the same – gently mocking or teasing, none taking the incident seriously.

"At least you gained something out of the experience."

"Finally, someone's interested in you."

Because of their reactions, Mike, who turns 30 years old this year, felt that there was no point in reporting the incident because he believed that the authorities would just make light of the situation in the same way.

These comments also frustrated him immensely and contributed towards his "spiral into a dark place", he said.

"It set an expectation in me that this isn't a big deal. And even if I do share it with other people, no one is ever going to think that I was taken advantage of."

For those reasons, till today, he has not sought professional counselling.

Mike's story is indicative of a broader problem in society – male victims of sex crimes tend to go unheard, are made fun of or dismissed.

This was made clear in the social media comments on a news report earlier last month, about a woman who was charged after allegedly committing sexual offences against a boy who was her primary school student and stalking him.

Court documents stated that the 34-year-old Singaporean hugged the boy, kissed him, sat on his lap and ground her body against him in a car at a multi-storey car park between February and October 2019.

On social media, many commenters made light of it, saying, for example, that the incident was a "dream" or "fantasy" for many school boys, or that they were envious of the victim.

Experts told CNA TODAY that such trivialisation or dismissive responses can have an impact on survivors that is as profound as the assault itself.

Ms Anita Krishnan-Shankar, a psychologist and sex therapist at Alliance Counselling, said this is especially significant for male survivors since their experiences are rarely acknowledged.

"When a man finds the courage to speak out – often after years of silence – and is met with disbelief or trivialisation, the effects can be devastating," she said.

"Such reactions reinforce feelings of shame, perpetuate the culture of silence and deeply undermine the survivor's sense of self-worth."

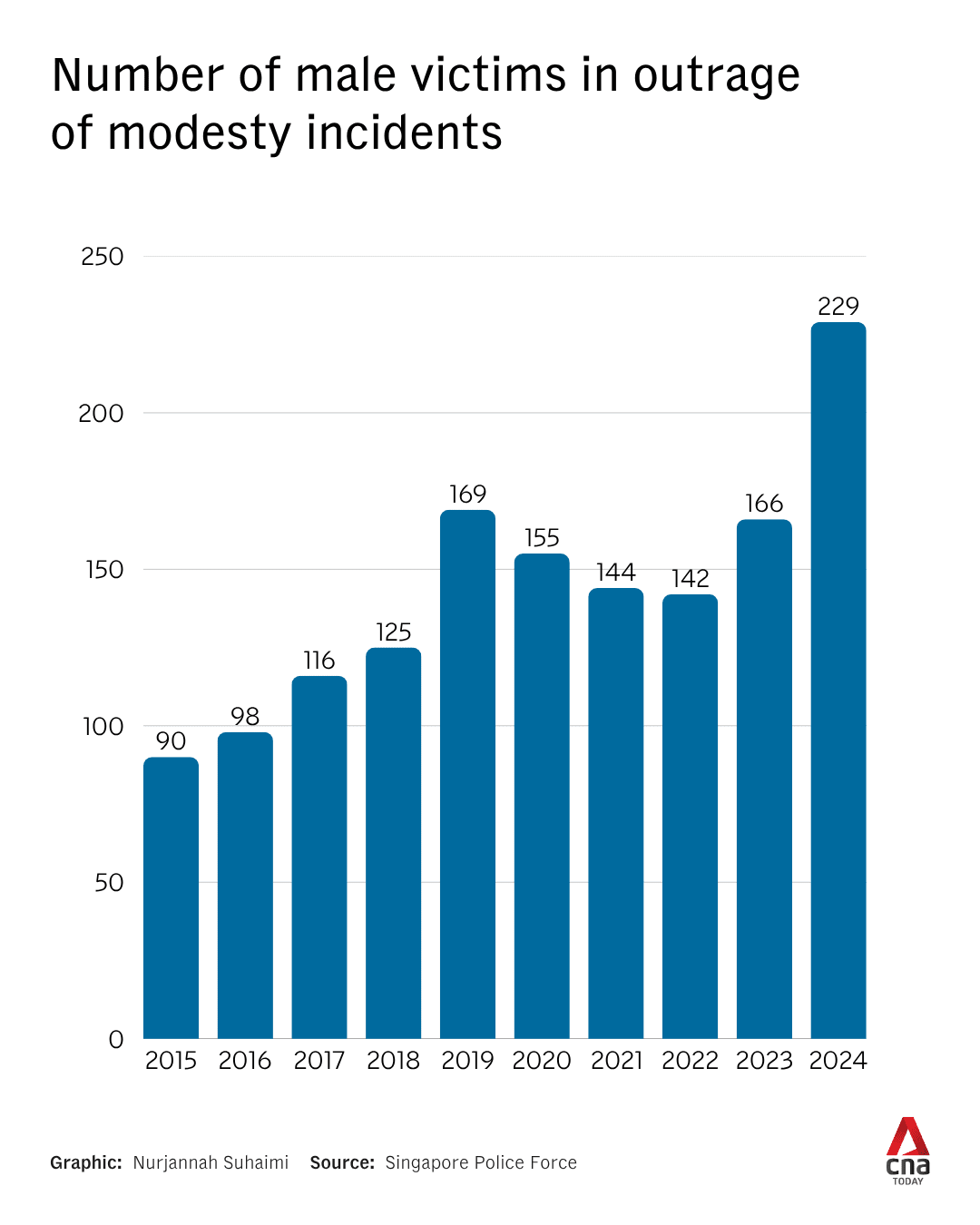

The latest figures from the Singapore Police Force show that the number of men who have had their modesty outraged has increased more than twofold since 2015.

In 2015, there were 90 such men who reported being victims of outrage of modesty. In 2024, that figure was 229.

Data from the police also showed there were between nine and 19 male victims of rape each year between 2020 and 2024. Data is only available for 2020 onwards, following a change in the Penal Code to recognise male victims of rape.

Meanwhile, the level of empathy from society towards male victims has not improved much over the years.

Dr Soh Keng Chuan, a consultant with the department of forensic psychiatry at the Institute of Mental Health (IMH), said that existing literature estimates the help and support for male victims to be "over 20 years behind" that of female victims.

HURT AND CONFUSION

It is common for male victims of sexual crimes to struggle to come to terms with traumatic events, mental health experts told CNA TODAY.

This was the case for Leonard (not his real name), a university student in his 20s.

As with other male victims who spoke to CNA TODAY, Leonard did not want to be publicly identified.

After a night out with a close female friend in June last year, they decided to head back to his home together to get some rest.

He thought nothing of sharing his bed with her, because they had done so previously while on holiday overseas and he considered her a trusted friend.

That night, though, she climbed on top of him while he was asleep and touched his private parts.

When he awoke to her touch, he pushed her off.

"At that point, I thought to myself, 'Why the **** is this happening? I don't want it'," Leonard said.

His memory of the incident was hazy, but he recalled feeling confused and shocked. She left his home shortly after that.

"I recalled thinking to myself that the girl – the perpetrator – was objectively kind of pretty. I was confused because I felt that I should have wanted it, but I did not."

Two days after the incident, the woman reached out to Leonard, but her communications only made him feel worse. She gave him a veiled apology through several text messages and they then had an hour-long call, during which she said she was distraught over the incident.

"When I saw her message, I thought, 'You're the one who did this to me, why are you the one telling me about your feelings?'," he said.

Leonard spoke to his two closest friends and his younger sister about the incident. His two friends were supportive, and one of them who knew the woman cut off ties with her.

His sister, however, was more dismissive of the situation, he said.

"It felt like there was a certain amount of aloofness (from my sister) when it came to the topic," he said.

It was hurtful, because when his sister had experienced a similar incident in the past, Leonard said he had responded in a supportive manner and stayed by her side.

After the incident, he found himself struggling to concentrate at work for several weeks. Now, he still enforces stronger boundaries with the people he interacts with and is more cautious of whom he trusts.

He added that if it were not for his two friends who provided a listening ear and comforted him, “things would have been a lot tougher for me”.

He has no plans to talk to other friends about the incident and simply wants to "bury it and move on".

"I think on some level, if I share my experience (with my friends), they might change their view of me in a way … Unless I think I can trust that person, it is better to just not test our friendship," he said.

TOUGH FOR MEN TO SPEAK UP

Deep-rooted gender norms form a large part of why attitudes towards male victims of sexual crimes are in stark contrast to those of women, experts told CNA TODAY.

Ms Caris Lim, the director of the women's care centre at the Association of Women for Action and Research (AWARE), said these attitudes include widespread beliefs that "sexual violence doesn't happen to men" and that men "should be strong enough to fend off perpetrators".

Some male victims also fear that the authorities will not believe that they could not stop the sexual crime themselves, Ms Lim added.

Associate Professor Razwana Begum, head of the public safety and security programme at the Singapore University of Social Sciences (SUSS), said that men are socialised to be "constantly sexually available and eager – making victimisation counterintuitive in the public psyche".

Women, on the other hand, are often seen as nurturing and non-aggressive, so their potential for being the aggressor and forcing others to do something unwanted is downplayed.

After CNA Lifestyle published an article in late July on why men require safe spaces and have support groups for their well-being, some comments left on social media echoed familiar tropes around masculinity. For example, some online users implied that men do not need safe spaces while others trivialised men's mental health.

These gender norms simultaneously fuel society's attitudes towards male victims and make it harder for them to be supported.

Dr Soh from IMH said that men who report their sexual assault experiences are more likely to encounter disbelief and even blame. They can also be perceived – by both others and themselves – as "weak" or "non-masculine" for failing to protect themselves.

"In scenarios where the perpetrator is also male, this adds another layer of stigma pertaining to their sexuality."

There are also structural and systemic barriers that hinder male victims from seeking help.

Dr Ong Mian Li, founder and principal clinical psychologist from Lightfull Psychology and Consulting Practice, said that many see support services as women-focused.

Men are more likely than women to think that seeking help or reporting sexual assault is seen as weak, a direct consequence of the role expectations that men tend to have, he said.

For instance, Assoc Prof Razwana of SUSS said that most rape crisis centres here were designed with women in mind.

The colours, decorations and sitting arrangement of these physical spaces may make men feel uncomfortable to step forward, and the language and terminology used in outreach materials may not resonate with men either.

Besides that, the number of male counsellors is limited, and some men may not feel comfortable sharing their experiences with female counsellors, she added.

Like many other male victims of sexual crimes, Leonard struggled with internal conflict about whether his own experience was "considered a crime".

"I was able to push her off after all," he told CNA TODAY.

But he added: "We tend to forget the 'sexual' part of 'sexual violence'. It's not just about physical strength to force someone down – it is also people who take advantage of the trust they have."

He did not report the incident to the police, because he was unsure if "anything would happen" since there was little evidence of what had transpired.

Mr Sanjiv Vaswani, a lawyer and founder of Vaswani Law Chambers LLC, said he has seen clients who were hesitant to pursue legal action because they feared that the perpetrator might retaliate with a false accusation against them.

In such cases, Mr Vaswani said that lawyers often “try our best to assure (our clients) that the police have very qualified investigators” and that the police also have specialised units and officers to handle sexual crimes.

The Singapore Police Force states on its website that it takes a "victim-centric approach" in its investigations and has measures to support victims. This includes support during the investigation process and during prosecution if the victim is required to testify in court.

Even when male victims end up going through with the legal process, many of them express reluctance about having to recount what had happened to them in court.

Mr Vaswani, who was a former Deputy Public Prosecutor with the Attorney-General's Chambers, said this is because they are fearful that their identity would be leaked, even though such cases often have a gag order in place that prevents the victims' names from being published.

Essentially, they fear being victimised again by toxic masculinity.

"For this reason, I quite honestly believe that the number of sexual assault cases against males that occur is far higher than the ones that lawyers actually see," Mr Vaswani said.

THE HARM IT CAUSES VICTIMS

As is the case with women, sexual crimes against men can be committed through online channels.

These include image-based sexual abuse, which encompasses the non-consensual sharing of intimate images or videos, the dissemination of content across adult websites or social media platforms, as well as threats to distribute such material.

The Singapore Council of Women's Organisations (SCWO), together with independent non-profit SG Her Empowerment (SHE), launched a one-stop support hub in 2023 for survivors of online harms known as the SHECares@SCWO Centre.

A representative from SHE told CNA TODAY that the centre supports an average of five to six cases of male survivors of online sexual abuse a year.

Victims of online sexual harms – such as the non-consensual sharing of intimate images or videos – can get access to services such as pro bono legal assistance, counselling and a telephone helpline and textline to get advice.

In one such case of online sexual abuse, the ex-girlfriend of Alex (not his real name) leaked a sex video and related photographs featuring him and another woman from a prior relationship.

She threatened to release the materials to coerce him into returning to a relationship with her – and the videos and photos were eventually circulated through a Telegram chat group and on Twitter (now X) without his consent.

Although the video was eventually removed by the ex-girlfriend, his colleagues who were in that Telegram group downloaded and circulated these videos in the office.

This incident made Alex extremely worried about keeping his job and his image at work, and made him feel as though his world was going to end.

He eventually sought help from his company's HR department. They arranged for him to work on a different office level, so he would not have to meet those colleagues at the workplace.

The SHE representative said that this highlights the importance of employers and other institutions in supporting survivors of online harms, regardless of gender.

Alex did not, however, opt to take up the support services that SHE offered. His decision not to do so reflects findings from studies that most male victims simply choose to suffer in silence.

A study by the National Institutes of Health in the United States found that men often adopt a "controlled" coping style marked by passive responses: They minimise the severity of the assault or simply accept their experience, Ms Krishnan-Shankar the psychologist said.

But this does not mean that male victims do not face deep psychological harm, said Dr Ong, the psychologist.

"For some, immediate trauma and, over time, conditions like PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder), depression, substance misuse and suicide risk increase by tenfold," he said.

For Mike, whose encounter with the woman on the MRT train occurred almost a decade ago, the effects remain to this day.

"After the incident, I felt I needed a lot more personal space, so I tend to avoid crowded trains or buses. I know this sounds crazy – a guy scared of people touching him – but this is how it affected my mentality when it comes to people around me.

"It left a mental scar. I don't think I've ever recovered from that."

HOW TO CHANGE MINDSETS

In recent years, the courts have made great strides in laying down rules on how to cross-examine survivors without victim-blaming and perpetuating myths on rape, Ms Lim from AWARE said.

Earlier last month, High Court judge Vincent Hoong told members of the Singapore Academy of Law that there is "no honour in extracting testimony through degradation, nor is there skill in exploiting the emotional vulnerability of a witness". He was speaking at a private event held at the State Courts on Jul 2.

Ms Lim said similar attention is needed for male victims to seek justice and navigate the criminal justice system safely.

On this point, Assoc Prof Razwana said that a good start would be to ensure that male victims are met with the same trauma-informed care offered to female victims.

"That means training officers to implement trauma-informed interview techniques, offering victims discreet options to report crimes and including male-victim case studies in police and prosecutorial training," she said.

Assoc Prof Razwana also advocated for the launch of national campaigns that include men as potential victims, and to fund studies to assess the prevalence of sexual crimes against men.

At the individual level, there is much to do in the form of educating the young in order to reshape cultural norms, Ms Krishnan-Shankar said.

"We need to rethink how we raise boys and teach them about emotional expression, consent, bodily autonomy and personal safety," she added.

"When boys are raised in environments where conversations about consent, boundaries and emotional safety are normalised, they are far more likely to recognise and report sexual harm if it occurs.

"Parents, teachers and caregivers must normalise asking for help and reinforce the message that speaking up about harm is a sign of strength, not weakness."

Lawyers can also play a role in helping male victims of sexual crimes.

Mr Vaswani the lawyer said that victims may sometimes be more closed off after experiencing a sexual crime due to the psychological impact, such as trauma, that the victims often face.

However, because lawyers have "limited skills" in providing psychological support, one option is that they can encourage victims to seek support from mental health specialists and support groups.

"I recall one such case where, after the victim came back (from counselling), he was much more at ease and was able to describe to us in detail what had happened. These details proved very useful in our eventual correspondence with the authorities on his behalf," Mr Vaswani added.

There has been some progress: Assoc Prof Razwana believes that the rise in the number of male victims in outrage of modesty cases reported by the police in recent years reflects a growing understanding of the issue.

"The numbers align with increased public awareness, education and a better understanding of what constitutes sexual violence – so victims are more empowered to report them. Also, successful prosecutions encourage more victims to come forward," she said.

Mike, the victim of sexual assault in 2017, acknowledges that public perception of the severity of such sexual crimes has changed to some degree from eight years ago.

On online forums, he has seen some comments of people empathising with male victims of sexual assault even if they had not experienced a similarly distressing situation, he said.

But the progress is far from enough, he added.

"I do not think the shift (in mindset) is significant enough for anyone to take a male victim seriously, like how they would if the victim were a female. As a guy, you can't imagine how distressed a man can be after being sexually assaulted by another woman, unless you have experienced it yourself," he said.

"I don't ever want to wish it on someone else. It was just suffocating. But I hope that anyone who has been through this knows that they are not alone."

WHERE TO GET HELP

- National Anti-Violence & Sexual Harassment Helpline: 1800 777 0000

- AWARE’s Sexual Assault Care Centre: 6779 0282

- SHECares@SCWO: 8001 01 4616