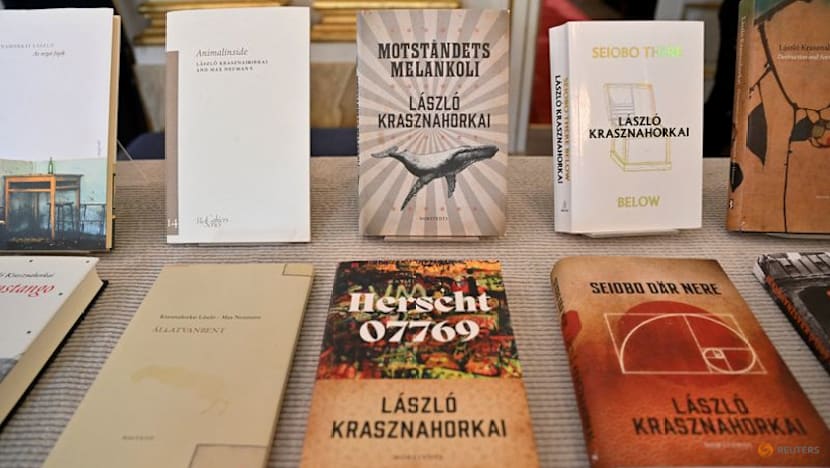

Hungary's 'master of apocolypse' Laszlo Krasznahorkai wins Nobel literature prize

Hungarian writer Laszlo Krasznahorkai poses for a photo in Salzburg on Jul 26, 2021. (File photo: AFP/Leo Neymayr)

STOCKHOLM: Hungarian writer Laszlo Krasznahorkai won the 2025 Nobel Prize in Literature, the award-giving body said on Thursday (Oct 9), "for his compelling and visionary oeuvre that, in the midst of apocalyptic terror, reaffirms the power of art".

Krasznahorkai, 71, is considered by many as Hungary's most important living author whose works explore themes of postmodern dystopia and melancholy.

"I'm very happy, I'm calm and very nervous altogether," the author told Swedish broadcaster Sveriges Radio.

"It is my first day as a Nobel prize winner," he said.

The Academy highlighted Krasznahorkai's first novel published in 1985, "Satantango", which brought him to prominence in Hungary and remains his best-known work.

The Academy called it "a literary sensation".

Krasznahorkai is "a great epic writer in the Central European tradition that extends through Kafka to Thomas Bernhard, and is characterised by absurdism and grotesque excess," the Academy said.

"But there are more strings to his bow, and he also looks to the East in adopting a more contemplative, finely calibrated tone."

Krasznahorkai was among those mentioned as a possible winner in the run-up to the prize.

"It is Laszlo Krasznahorkai's artistic gaze, which is entirely free of illusion and which sees through the fragility of the social order, combined with his unwavering belief in the power of art that has motivated the Academy to award him this prize," Academy member Steve Sem-Sandberg said.

The Nobel Prize comes with a diploma, a gold medal and a US$1.2 million prize sum.

"MASTER OF THE APOCALYPSE"

Krasznahorkai, the second Hungarian to win the prize, has been described as the postmodern "master of the apocalypse".

"He is a hypnotic writer," Krasznahorkai's English language translator, the poet George Szirtes, told AFP.

"He draws you in until the world he conjures echoes and echoes inside you, until it's your own vision of order and chaos".

Exploring themes of postmodern dystopia and melancholy, his first novel brought Krasznahorkai to prominence in Hungary and remains his best-known work.

"The novel portrays, in powerfully suggestive terms, a destitute group of residents on an abandoned collective farm in the Hungarian countryside just before the fall of communism," the Academy said.

Until now, the late Imre Kertesz was the only Hungarian to win the Nobel literature prize in 2002 for his semi-autobiographical novel "Fatelessness" about surviving the Holocaust.

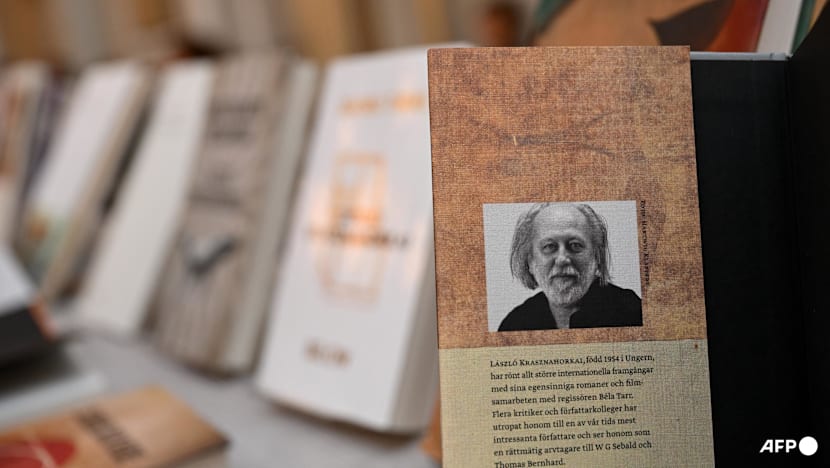

Born in Gyula, a small town in southeast Hungary in 1954, Krasznahorkai grew up in a middle-class Jewish family.

He has drawn inspiration from his experiences under communism, and the extensive travels he undertook after first moving abroad in 1987 to West Berlin for a fellowship.

His novels, short stories and essays are best known in Germany - where he lived for long periods - and Hungary, where he is considered by many as the country's most important living author.

Critically difficult and demanding, his style was described once by Krasznahorkai himself as "reality examined to the point of madness".

His penchant for long sentences and few paragraph breaks has also seen the writer labelled as "obsessive".

Asked about the apocalyptic images in his work, Krasznahorkai said: "Maybe I'm a writer who writes novels for readers who need the beauty in hell".

Krasznahorkai had a close creative partnership with Hungarian filmmaker Bela Tarr. Several of his works have been adapted into films by Tarr, including "Satantango" and "The Werckmeister Harmonies".

Their collaboration has garnered critical acclaim. In 1993, he received the German Bestenliste Prize for the best literary work of the year for The Melancholy of Resistance.

PAST WINNERS

Past winners of the 11 million Swedish crown literature prize include French poet and essayist Sully Prudhomme, who bagged the first award, American novelist and short story writer William Faulkner in 1949, Britain's World War Two Prime Minister Winston Churchill in 1953, Turkey's Orhan Pamuk in 2006 and Norway's Jon Fosse in 2023.

Last year, the award went to South Korean author Han Kang, the first Asian woman to win the Nobel.

The Academy has long been criticised for the overrepresentation of Western white men among its picks.

Women are vastly under-represented among its laureates - just 18 out of 122 since it was first awarded in 1901.

The Swedish Academy has undergone major reforms since a devastating #MeToo scandal in 2018, vowing a more global and gender-equal literature prize.

Over the years, the choices made by the Swedish Academy have drawn as much ire as applause.

In 2016, the award to American singer-songwriter Bob Dylan sparked criticism that his work was not proper literature, while Austrian Peter Handke's prize also drew criticism in 2019.

Handke had attended the funeral in 2006 of former Yugoslav President Slobodan Milosevic, seen by many as responsible for the deaths of thousands of ethnic Albanians who were killed in Kosovo and the displacement of almost 1 million others during a brutal war waged by forces under his control in 1998-99.

Prizegivers have also in the past been accused of being snobbish, of having an anti-American bias and of ignoring some of the giants of literature, including Russia's Lev Nikolayevich Tolstoy, France's Emile Zola and Ireland's James Joyce.