ASIA’S FUTURE CITIES: Yangon lacking resilience to face future disasters

A severe global climate forecast has Myanmar facing a potentially dire future: a dramatic five-degree temperature increase by the end of the century, earthquakes, flooding and mass in-migration to cities.

There are many queries about whether Yangon is resilient enough to handle future climate change. (Photo: Jack Board)

YANGON: Nothing is normal these days when it comes to Myanmar’s weather.

In Yangon, residents talk about a time when they used to wear sweaters or scarves in the colder months, when the early morning was crisp and people would exercise to stay warm.

Not anymore.

Yet, this rise in temperature is just a small indicator of the unparalleled challenges facing the country’s largest city.

A more severe global climate forecast has Myanmar as a whole facing a potentially dire future: a dramatic five-degree temperature increase by the end of the century, earthquakes, flooding and mass in-migration to cities.

“It’s severe,” said high profile local meteorologist Dr Tun Lwin. “This is a problematic country.”

For nearly 40 years now, Myanmar has been experiencing “dramatic” climate change, according to Tun Lwin. It has been a slow burn that is expected to only get worse in the coming decades.

“We’re now facing a new standard of climate norms. At first we considered it as adverse weather, but this adverse weather has happened now since 1978,” he said.

Monsoon patterns have become shorter over this period and rain less consistent, timely or predictable. Farmers feel it now. But urbanites are unlikely to be able to shelter in naivety for long.

The world is changing, however. Myanmar is locked between two of the biggest carbon polluters in the world – China and India. Its climate fate may ultimately be decided by others.

And there are looming questions about the city and its people’s resilience in the face of what is expected to come.

As despairing rural populations struggle to deal with the changes, “it increases the likelihood of conditions in Yangon becoming worse and worse”.

On the city’s door, evidence of a worsening climate is starting to show effect.

Within Yangon’s bounds, agricultural areas around Kawhmu are becoming unliveable, according to the residents who have worked the land for generations.

Locals describe an irrepressible heat. They have watched waterways disappear and salt water from the nearby bay intrude beneath their farming land.

In the peak of the dry season, children walk miles to collect fresh water in buckets tied to a wooden pole strapped across their backs. In the past they would have collected it from the river or healthy irrigation streams that have long disappeared.

“In our region, the seasons have become chaos,” Hla Aye explained. “Of course I am seriously concerned about climate change. Especially, I worry for the younger generations.”

These parts are low-lying and close to the Bay of Bengal. A lack of fresh water is the primary concern for now. “If you want fresh drinking water you would need to dig over 125 feet down,” mushroom farmer Zin Yaw claims.

By 2030, the sea level rise would mean annual losses of more than US$500 million if little action is taken between now and then. The figure exponentially increases, decade by decade.

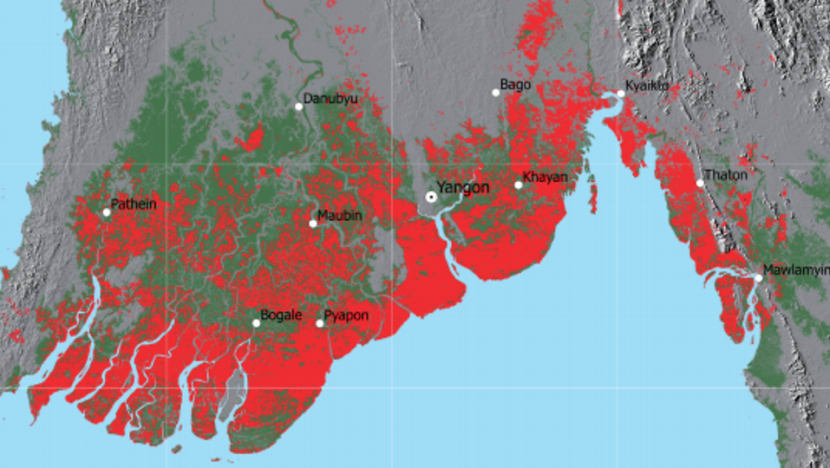

The major danger then arises during wreckful storm surges and subsequent flooding. Cyclone Nargis devastated the country in 2008, killing an estimated 138,000 people, and in doing so became the second most deadly cyclone in history.

Kawhmu, just across the Yangon River from dense populations, was seriously impacted by flooding at that time and is prone to be hit again.

Mother Nature has also been shifting her destructive eye towards Myanmar’s more heavily populated regions – around Yangon and the wider delta.

Over more than 120 years of recorded storm experience, only 7 per cent of systems hit the deltaic region compared to 90 per cent on the west coast, says Ye Ye Nyen, the director of the Department of Meteorology and Hydrology (DMH) in Yangon.

The trend is shifting, bringing more powerful low-pressure systems, just like Nargis, to the delta, an area less prepared to deal with the effects.

“Abnormal tracts are coming. This is really a symbol of climate change,” she said.

Still, she doubts whether urban residents have much understanding of the trend. “Myanmar people only think short term. We don’t live thinking about the future. Everyone is not too worried,” she said.

“People are only concerned by what they need. For farmers, when the water is gone then they cannot grow their crops,” said Win Mio Thi, the executive director of EcoDev.

“In the urban areas there is pollution there, greenhouse gas or climate change, it’s not part of their daily concerns. They might know but they don’t care.”

He says economic incentives, government regulation and education are the key to ensuring city dwellers are best prepared for the future. And still, he warns, it may not mean Yangon is best placed for long-term survival.

“Even if we have a positive outlook, what will be the ground reality? That’s difficult to predict. It’s not expected to be what we desire.”

The challenge is a steep one, currently being posed to a recently elected democratic government, being steered by Aung San Suu Kyi. Environmental issues are on the agenda, but the government’s focus is being stretched.

“Even though the NLD doesn’t know much, they consider this an important priority. It gives us a chance, but not enough,” Tun Lwin said.

But as with many least-developed nations, budgets are tight and perfect-world government solutions are impossible to implement.

“I am worried but based on our own budget we cannot afford,” Ye Ye Nyen said. “It’s very important for us. But how can we hope for something out of reach.”

In the meantime, current behaviours in the city continue to hinder the situation.

In the low-lying township of South Okkalapa, about 10km north of downtown Yangon, persistent sand dredging in Pazundaung Creek has seen its banks widen further by the year. Even in the dry season, waters gently flow where children once played football.

“I want to move to another place now because I’m getting more worried every year about the flooding,” she said.

So what will it take to get the climate issue to be taken seriously? Tun Lwin hopes that it will not be another serious disaster, like Nargis.

“I wish not, but I can’t promise.”