China's concertgoers splash the cash, but is revenge spending sustainable to rock the economy?

Concerts have been relentlessly trending on Chinese social media in recent months, and in the first half of the year, more than 500 large-scale gigs and music festivals were held in China. (Illustration: SCMP/Brian Wang)

- More than 500 large-scale concerts and music festivals have been held in China since the start of the year, bringing in 2.5 billion yuan (US$350 million) in ticket sales

- Beijing had hoped consumption could be a primary driver for China’s economic recovery, but analysts have questioned its sustainability

Since China lifted its coronavirus-related restrictions in December and entertainment venues were once again allowed to open for business, in-person activities have been in high demand, with fans frantically seeking spare concert tickets.

“It’s like a feeling of rediscovered appreciation, and is a form of revenge spending,” said recent college graduate Liu Ying.

The 22-year-old has attended three concerts this year, spending over 7,000 yuan (US$980) on tickets.

“Prior to the pandemic, I didn’t consider it necessary, but afterwards, I realised that opportunities such as attending concerts and travelling can sometimes be once-in-a-lifetime,” she added.

“[The pandemic] made me realise that life is about living in the present and embracing as many experiences as possible.”

Concerts have been relentlessly trending on Chinese social media in recent months, and in the first half of the year, more than 500 large-scale gigs and music festivals were held in China.

And they combined to rake in 2.5 billion yuan in ticket sales, with more than 5.5 million tickets sold, according to the China Association of Performing Arts.

The three months of the second quarter alone accounted for nearly 90 per cent of the ticket sales.

More broadly, the number of for-profit performances - including pop concerts, dance shows and operas - in the first six months of the year surged by 400 per cent to 193,300, while ticket sales jumped by 673 per cent to 16.8 billion yuan and attendances increased by more than tenfold to over 62 million.

But while the concert market is experiencing a significant boom, it stands as an outlier to the broader economic recovery, which has been gradually losing steam.

The stark contrast has pointed to the uneven path to recovery across sectors and raised concerns about whether consumption alone can be relied upon as a primary driver for China’s economic recovery.

During the week-long Labour Day holiday in May, concerts and music festivals generated more than 1.2 billion yuan of consumer spending – excluding ticket sales – including transport, hotels, dining services among others.

“As the impact of the pandemic eases, there is a sudden release of emotions that have been suppressed for three years and a strong desire to temporarily break free from the current state,” said 28-year-old Shi Xiangyu, who now works in Hong Kong.

Shi has attended three concerts this year and has two more lined up in the coming month.

“It’s almost like an experiment to validate the right to freedom through travelling and attending concerts,” she added.

“However, frequent and high levels of spending may not be sustainable. I believe it is important to balance spending capability with needs.”

Similar revenge spending has been seen in other sectors, with long queues in front of restaurants, packed sporting events, crowded tourist attractions and skyrocketing hotel and flight ticket prices.

But in contrast to the robust rebound in some consumer sectors, there is a sluggish recovery of consumer durables – including vehicles and household goods – and depressed property sales amid China’s post-reopening economy.

Real estate investment dropped by 7.9 per cent in the first six months of the year, while weak demand is further slashing property prices.

That, in turn, has pushed down big budget spending on household appliances, construction and furniture.

“Concerts are high-end consumption, targeting urban middle class whose income was affected less during the COVID years,” said Wang Dan, chief economist at Hang Seng Bank China.

“The exceptionally high stress in the job market also means people are willing to spend more to relax. This is a typical lipstick economy phenomenon – during severe economic downturns, consumption of things that can provide emotional value tends to go up.

“However, income growth has permanently slowed, the hype in concert spending is therefore not sustainable.”

China’s recovery has been hit by domestic and international headwinds, including a curtailed property market, as well decreasing demand for exports, as well as weak confidence in the private sector dampening consumer confidence.

In the second quarter, China’s economy grew by 6.3 per cent, year on year, although analysts pointed to the low base from last year, when the economy stalled amid nationwide lockdowns.

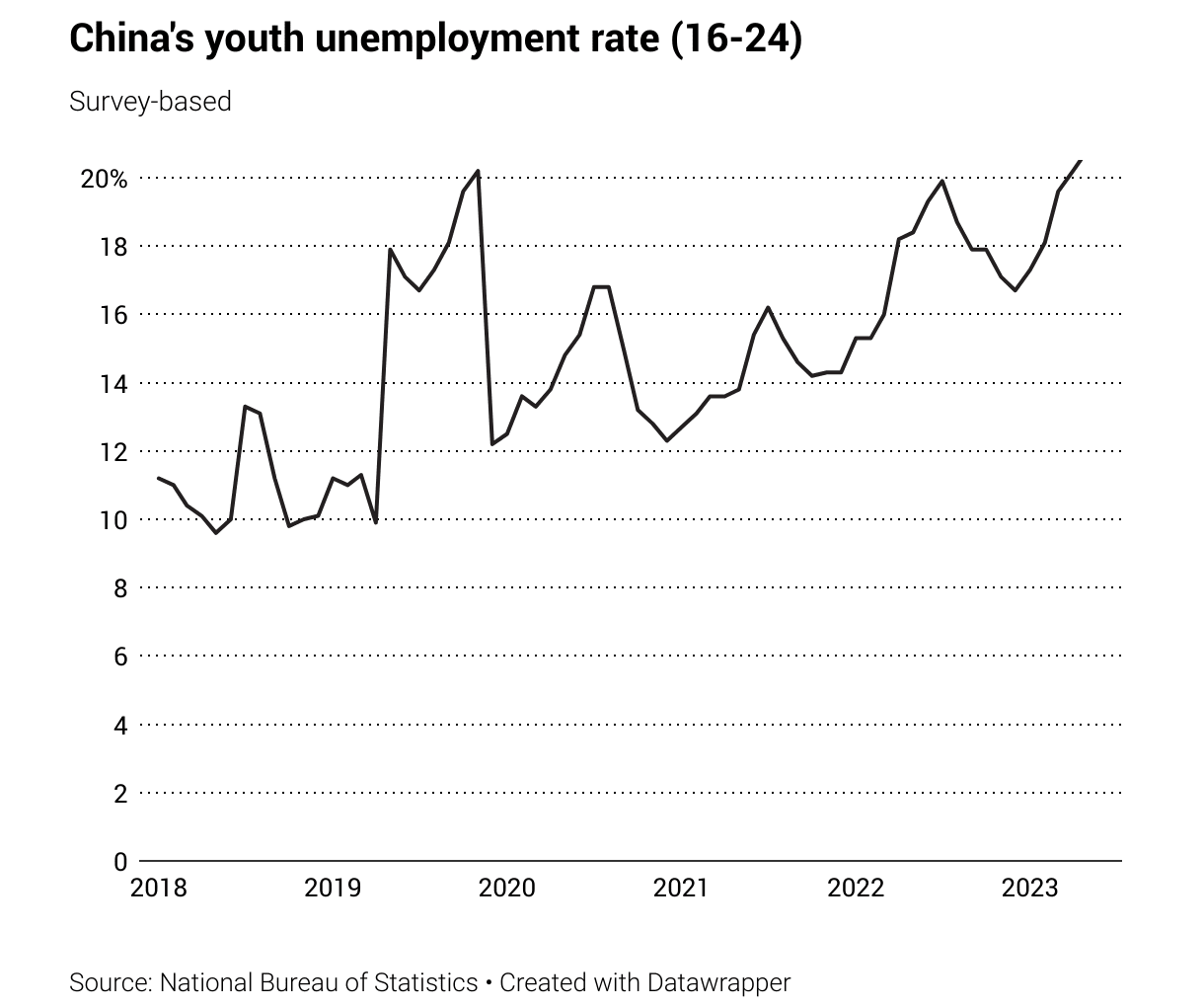

In addition, rising uncertainties in the job market, overshadowed with pessimism and unease, have also prompted residents to cut spending.

The jobless rate for the 16 to 24 age group reached an unprecedented 21.3 per cent in June, having been on an upwards trajectory since 2020.

It is expected to rise further in July and August, as a record 11.58 million university graduates are set to leave campus and flood the job market this year.

Fears over widespread lay-offs, pay cuts and age discrimination against workers as young as 30 are also seen to have stopped consumers from overspending.

And one or two policies will not be able to stimulate spending, while consumers’ income and confidence are the keys to boosting consumption, said He Jun, a researcher at Anbound, an independent think tank.

“People will naturally spend more if their income increases; people will dare to spend and even borrow to increase spending if they have confidence in the future, because they believe in their ability to repay the debt,” He said.

“The recovery of consumption cannot be realised through macroeconomic control, but are results of economic improvement.

“Difficulty in employment will significantly suppress consumption, with more individuals opting for a lying flat mentality.”

The lying flat movement represents the mindset of lying down instead of studying hard, finding a high-paid job, buying a home or even starting a family early in life.

“Policies aimed at supporting and stimulating consumption will be implemented, but it is crucial for these policies to identify the root causes,” added He.

He said that even if the government opted for unconventional helicopter money, also known as a helicopter drop, where large sums of money are printed and distributed to the public to spur economic growth, individuals lacking confidence and income may not necessarily increase their consumption even after receiving the cash.

“They will primarily satisfy basic needs and allocate the funds to debt repayment, thereby reducing their personal balance sheets,” said He.

China has been offering tax cuts and discount coupons in an attempt to boost spending, but the results have been inconspicuous.

But despite the government’s goal to prop up the economy with consumption, it will be hard to realise, said Peng Peng, executive chairman of the Guangdong Society of Reform, a think tank connected to the provincial government.

Peng added that consumption has been the weakest among the three pillars of China’s economy, which also include investments and exports.

“Currently, China’s foreign trade is flopping, investment in real estate is weak, and low-cost consumption dominates consumer spending,” Peng said.

“As a result, without economic recovery, it is difficult for consumption to thrive comprehensively. The relationship between consumption and the economy should be mutually reinforced.”

Related:

Consumption accounted for 32.8 per cent of China’s gross domestic product growth in 2022, down from 54.5 per cent in 2021, and still short of over 80 per cent for many developed countries.

And while quick-fix solutions, such as cash transfers to low-income families or just a general transfer, would be effective, it is not a monetary tool the Chinese government is used to, added Wang at Hang Seng Bank.

“Now the economic policies still focus on economic security and long-term strength in the supply chain. The short-term stimulus for consumption or investment will not be prioritised,” she added.

In the next two to three years, household consumption will command a higher share of the economy than investment, said Xu Tianchen, an economist with the Economist Intelligence Unit.

But the trend will be primarily driven by a decline in investments – especially as governments and property developers deleverage – rather than Chinese consumers getting richer and becoming more willing to spend.

“Technically, the government is supposed to increase expenditure to bridge the shortfall in private demand, for example by handing out cash transfers. But now its ability to act is being constrained by fiscal strains and perhaps the prioritisation of debt resolution in the agenda,” said Xu.

“This partly explains why government commitment to boosting income and consumption hasn’t met with actual deeds.

“Against that backdrop, policymakers are mostly likely to let things run their own course – with limited support provided – and consumers will rely on their own means.”

This article was first published on SCMP.