analysis Asia

From sand to supply chain power: Can India weaken China’s grip on rare earths?

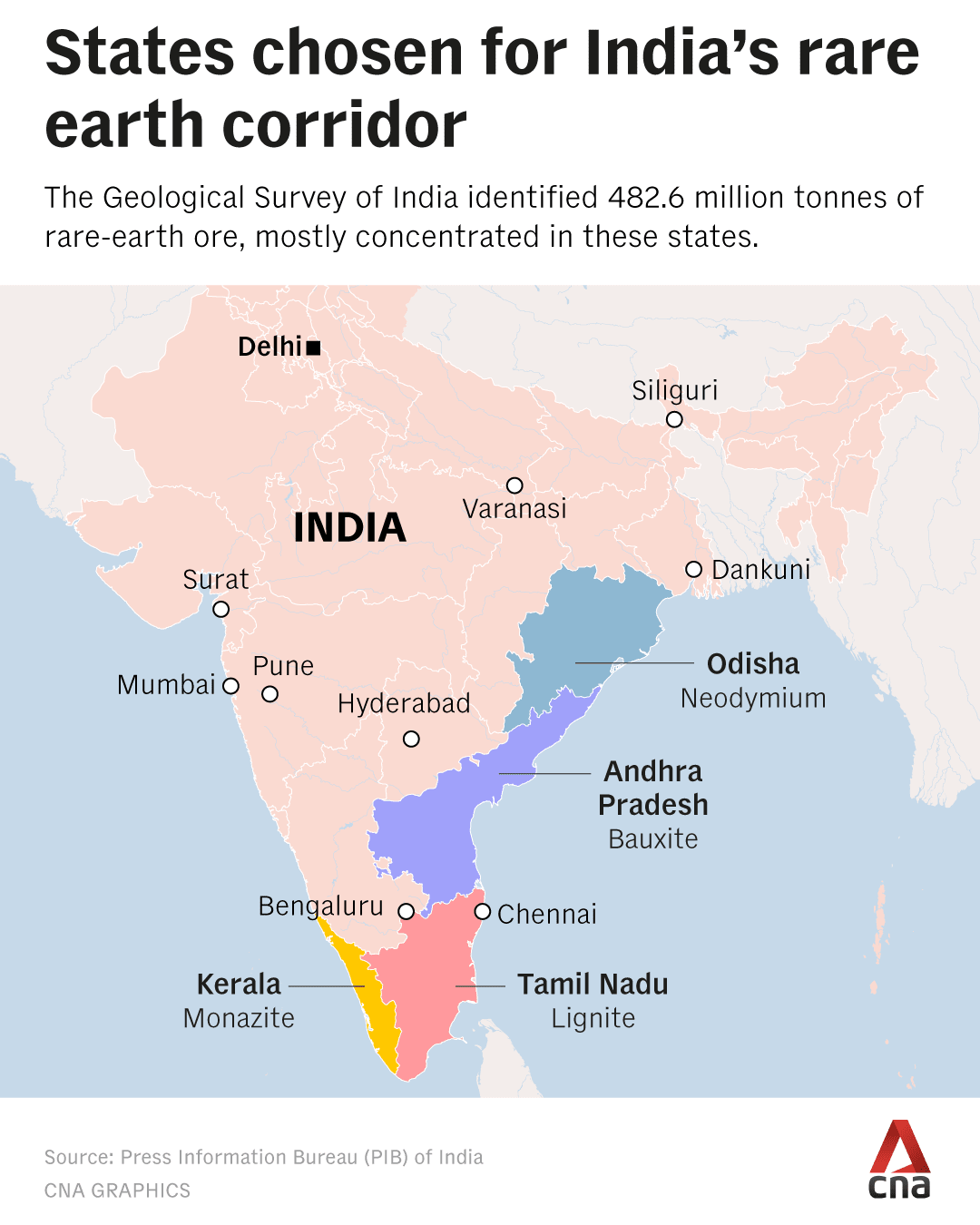

Announced in India’s Union Budget this month, the proposed Rare Earth Corridor across Odisha, Kerala, Andhra Pradesh and Tamil Nadu marks what analysts say is New Delhi’s bid to convert mineral reserves into strategic clout.

Samples of rare earth minerals from left, Cerium oxide, Bastnasite, Neodymium oxide and Lanthanum carbonate are on display during a tour of Molycorp's Mountain Pass Rare Earth facility in Mountain Pass, California June 29, 2015. (Photo: Reuters/David Becker)

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

SINGAPORE: Announced in India’s Union Budget this month, the proposed Rare Earth Corridor across Odisha, Kerala, Andhra Pradesh and Tamil Nadu marks what analysts say is New Delhi’s bid to convert mineral reserves into strategic clout.

India holds the world’s third-largest reserves of rare earths at 6.9 million tonnes, behind China and Brazil. Yet it struggles with mining and processing them, contributing less than 1 per cent of global production.

China, by contrast, commands the critical stages of the supply chain. According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), it accounts for roughly 60 per cent of global rare earth mining and 91 per cent of refining output - the stages where real leverage lies.

That control was evident last year when Beijing imposed export restrictions on rare earth elements and related products, including shipments to India.

Rare earth elements - a group of 17 metals - are essential to electric vehicle (EV) motors, wind turbines, semiconductors, smartphones, aerospace systems and defence equipment, placing them at the centre of national security strategy.

Saurabh Priyadarshi, Mining and Metals Advisor at Geoxplorers Consulting Services, characterises them as “the vitamins of modern technology”, used in small quantities yet indispensable to advanced systems.

India’s ambition is to build a fully integrated domestic ecosystem – from rare earth oxides to finished magnets.

The proposed corridor, the government said, aims to build a reliable domestic supply of rare earth permanent magnets, which it described as “critical”.

It will promote mining, processing, research and manufacturing of rare earth materials to reduce import dependence and strengthen India’s position in global advanced materials value chains, it added.

The central challenge now is whether India can realistically move from being a resource holder to processing power - and how long that transition might take.

Rajnish Gupta, Partner at EY’s Tax and Economic Policy Group, told CNA that India faces two major challenges: “access to processing technology” and “disposing of tailings which can be radioactive” given the presence of thorium in rare earth reserves.

Despite these hurdles, he said government support is critical. Without it, India could find itself in the same position a decade or two from now.

“You have a competitor who has state support, technology, scale, pricing power and sees this as a strategic lever,” he added.

HOW FEASIBLE IS THE CORRIDOR?

India’s rare earth wealth is concentrated largely in coastal beach sands.

Rare earths in beach sands are not freely occurring particles but are embedded within specific minerals that must be chemically separated, PV Sunder Raju, Chief Scientist at the National Geophysical Research Institute (NGRI), a research laboratory of the Council of Scientific & Industrial Research (CSIR), told CNA.

He added that the composition of deposits varies along the proposed corridor, as the sands originate from eroded inland rocks. As a result, extraction technologies must be tailored to each location.

Globally, rare earth elements are categorised into light and heavy types.

Light rare earths, including neodymium and praseodymium, are relatively abundant in India and can be refined to high purity levels. Heavy rare earths, such as dysprosium and terbium, however, are not available in extractable quantities in India’s currently exploited reserves, according to India’s Department of Atomic Energy (DAE).

Heavy rare earths are critical for high-performance magnets used in electric vehicles and defence systems, while light rare earths are essential for semiconductors and electronics.

The absence of heavy rare earths presents a structural limitation.

EY’s Gupta noted that 60 to 70 per cent of heavy rare earth supply currently originates from Myanmar, much of which is processed in China.

“That supply is very restricted. (Heavy rare earth) is there in Myanmar, there's some of it in China, which is also a choke point," said Gupta.

India imported between 80 and 90 per cent of its rare earth magnets and related materials from China in the financial year ending March 2025, amounting to about US$190 million, according to government data.

To reduce such dependence, the Indian government has pursued overseas resource acquisition. In 2019, it set up Khanij Bidesh India Limited (KABIL), a state-owned joint venture company tasked with securing critical and strategic mineral assets abroad to ensure a stable supply for domestic use.

In January 2024, KABIL signed an agreement with Argentina for lithium exploration and mining projects, and has reportedly been in discussions regarding lithium assets in Australia.

Raju said similar overseas arrangements elsewhere could be explored for rare earths.

More recently, India held discussions with Brazil, Canada, France and the Netherlands on cooperation in exploration, extraction, processing and recycling of critical minerals, with a focus on rare earths, according to a Reuters report on Feb 10.

Another major constraint is radioactivity. Rare earth beach sands often contain thorium, a radioactive metal, bringing mining under atomic energy regulations.

Priyadarshi explains that the presence of monazite - a thorium-bearing mineral - historically led to India’s beach sand deposits being classified as “prescribed substances”.

This designation mandated strict oversight by the Atomic Minerals Directorate (AMD) under the DAE, effectively restricting private sector participation due to the strategic sensitivities surrounding nuclear materials.

This means government-backed entities will continue to dominate mining, while private players are likely to focus more on processing and downstream manufacturing.

That would leave private players reliant on state-run mining operations for raw materials - operations that, according to local reports, have faced delays in the past.

At present, India has only one operational rare earth mine in Andhra Pradesh, run by the state-owned IREL - formerly India Rare Earths Ltd.

Coastal regulations add further complexity. Monazite occurs in areas governed by Coastal Regulation Zone rules, as well as mangrove and habitation protections.

Even where deposits are identified, timelines for mines to become operational remain long.

Greenfield exploration alone can span three years, Priyadarshi noted, while the subsequent “regulatory matrix” of environmental and techno-economic clearances can add another two to five years before private players can begin mining operations.

MINING IS THE EASY PART

All experts CNA spoke to were clear on one point: mining is only the beginning.

“The heart of the rare earth supply chain is processing,” said Raju, noting that China’s real advantage lies not just in mining but in decades of metallurgical refinement. This includes acid leaching, solvent extraction and highly customised separation technologies.

Unlike iron ore or copper, rare earth separation is not standardised.

“Kerala sands differ from Odisha sands,” Raju explained, adding that each deposit requires tailored extraction chemistry.

“The processing technology also varies. If one develops the technology, it may not be suited for another location’s REE (rare-earth elements) oxides.”

Amit Bhargava, Partner and National Leader - Metals and Mining at KPMG India, said that although India has been developing technologies to process rare-earth oxides, it still completely depends on foreign technology for subsequent stages - alloying and producing rare earth magnets.

The DAE has similarly stated that large-scale facilities for magnet manufacturing are “non-existent” due to lack of technology.

Crucially, this technology cannot simply be imported. China tightly guards its processing know-how, and Raju cautioned that even where equipment is available, it may not suit India’s specific deposits.

To address this gap, India has begun investing in research and development facilities. A facility was inaugurated at the Bhabha Atomic Research Centre in 2023, while a separate public–private initiative aims to produce 5,000 tonnes of magnets annually by 2030.

In November 2025, the government approved a 72.8 billion rupees (US$802 million) Rare Earth Permanent Magnet (REPM) manufacturing scheme aimed at producing 6,000 tonnes of rare-earth magnets annually within seven years.

The scheme offers subsidies worth 7.5 billion rupees to attract up to five companies through a global bidding process to establish manufacturing facilities in India.

Experts told CNA the funding is insufficient to fully develop a rare-earth magnet industry, but it serves as an initial step by the country and will attract private investment.

Environmental management remains another major hurdle. Separating rare earth metals requires significant quantities of acids and generates radioactive and chemical waste, Raju noted.

He added that China’s rapid scale-up was partly enabled by a willingness to tolerate environmental damage that others are less inclined to accept.

The question for India then becomes a matter of time, said experts.

Japan’s investment in rare earth processing accelerated after China imposed export restrictions in 2011. More than a decade later, it still imports 60 to 70 per cent of its requirements from China, according to EY’s Gupta.

Experts CNA spoke to believe that while India is unlikely to match China’s dominance, it could take eight to 10 years to build a functional processing ecosystem - assuming policy continuity, sustained capital investment and technological progress.

STRATEGIC DEFENCE: AVOIDING THE CHINA PRICE TRAP

The global REE market is projected to be worth US$7.8 billion in 2026 and grow to US$15.4 billion by 2033, according to Persistence Market Research. By comparison, oil and gas is a multi-trillion-dollar industry, and the semiconductor market exceeds US$600 billion.

Yet, despite its relatively modest size, the downstream impact of rare earth on EVs, wind energy, semiconductors, aerospace, and defence is enormous. That asymmetry - a small upstream market with vast strategic consequences - makes rare earths difficult for countries like India to ignore.

According to an Amicus Growth Advisors report in December, China’s export controls in 2025 triggered significant global supply disruptions, forcing automakers such as BMW and Ford to halt assembly lines.

“The disruption was not caused by a mine collapse or natural disaster. It was caused by a regulatory pencil stroke,” the report noted.

Industry players warn that China can also depress prices temporarily to undercut emerging competitor nations in rare earth processing and magnet manufacturing.

“China, when it sees that there are other factories coming up all over the world, they drop the price so that no one will buy a more expensive product from another country,” said Bhaktha Keshavachar, founder and CEO of Chara Technologies, an Indian startup that has developed rare-earth-free motors.

To counter this, Priyadarshi said the Indian government could introduce floor pricing mechanisms.

“Floor price is where the government assures manufacturers that the sale price of their product will not go below a certain level. If it goes below that price, they will be compensated for the difference,” said Geoxplorers Consulting Services’ Priyadarshi.

He noted that the United States has adopted similar support mechanisms for critical minerals and suggested India may require comparable policy tools.

More broadly, analysts argue that the global industrial thought process has shifted.

“Ten years back, it was all about efficiency. Today it is not just about efficiency; it is also about resilience,” said EY’s Gupta.

For India, the Rare Earth Corridor is therefore less about immediate cost competitiveness and more about reducing strategic vulnerability. The objective, experts told CNA, is not purely commercial optimisation but supply security.

“In the future, people will not fight for water or weapons anymore, they will fight for minerals,” said Raju.