Malaysia’s ECRL: Megaproject could shake up national, regional connectivity, but single-track design makes it ‘challenging’

In the final instalment of a four-part series on the East Coast Rail Link (ECRL), CNA finds out how the railway might alleviate stifling road congestion, better connect east coast towns and alter regional shipping routes, alongside the potential hurdles it faces.

Aerial view of the main ECRL station for Kuantan in nearby KotaSAS, Pahang. (Photo: CNA/Hari Anggara)

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

KOTA BHARU/TEMERLOH, Malaysia: The main bus station in Kota Bharu, Kelantan is a makeshift one, made up of a canteen, snack kiosks and ticket booths under a large zinc roof.

This bus station, a key transport hub with multiple bays and a steady stream of boarding and alighting passengers, was never intended to be permanent, but has been in operation for more than 12 years.

In July 2022, the state government announced that a new bus terminal, expected to be built further out of the city in Tunjung, would be completed by the end of 2025.

But in March last year, local authorities said the new bus station would be completed by 2027 instead, with works to begin early this year.

They said the delay is aimed at synchronising the bus terminal’s completion with the start of the new East Coast Rail Link (ECRL), which will reduce the travelling time from Gombak, near Kuala Lumpur, to Kota Bharu from at least seven hours by car to four hours by train.

The site of the new terminal is just a short drive away from the planned ECRL station for Kota Bharu.

Until then, Wan Hakim Wan Zuhairi continues to make the same trip by bus, alighting at the old terminal. The Gombak-Kota Bharu journey usually takes eight hours.

The 21-year-old economics undergraduate, who studies at a university in Gombak, is on his mid-semester break and back to see his parents in Kota Bharu, one of the three to four trips he makes to his hometown in a year.

“The ECRL is something that I’ve been waiting for for a long time,” he told CNA, a duffel bag and badminton racquet slung over his shoulder.

Wan Hakim said students in his university and elsewhere in the Klang Valley had long given feedback to authorities about the lack of transport options for those who needed to make frequent trips to the east coast, but this had largely fallen on deaf ears.

“I usually drive, but during the festive season the journey by road can take 12 hours or more, so I prefer to sleep on the bus,” he said, highlighting that friends had been caught in the congestion for up to 20 hours.

Taking a flight could be expensive and is only a last resort for emergencies, while trains on the existing KTM rail network take 12 hours to reach Kota Bharu, he said.

“I support this project,” Wan Hakim said, noting the socioeconomic benefits the ECRL could also bring to the less-developed east coast. “But it’s only expected to be completed in 2026, and I will be graduating (in 2025).”

Last November, CNA drove from Gombak to Kota Bharu, stopping at the small towns in between, to experience the road conditions and chat with locals about how they criss-cross the east and west coasts in the absence of a viable and modern rail link.

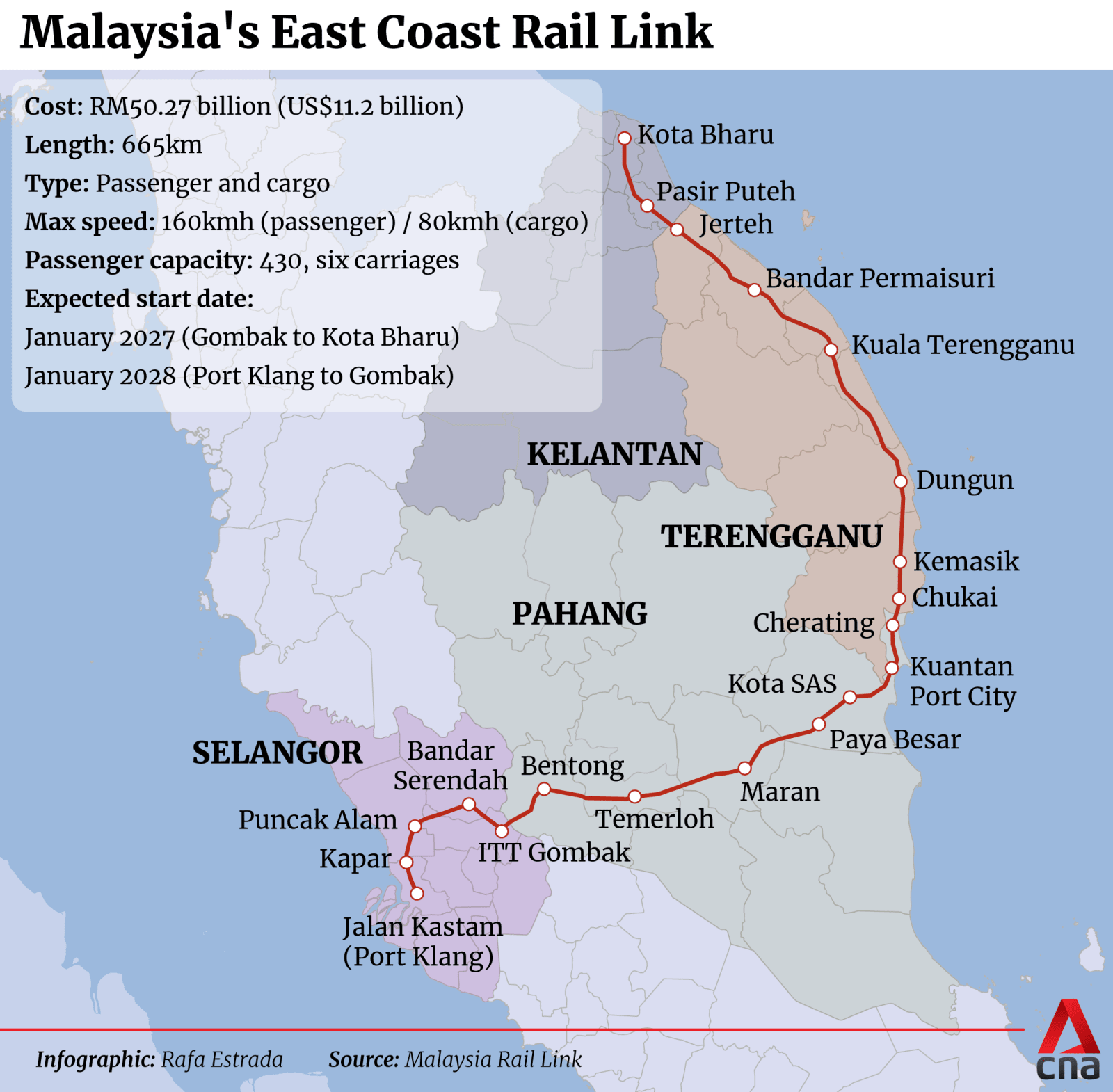

Construction of the ECRL network from Gombak to Kota Bharu is expected to be ready in December 2026 with services starting in January 2027.

The railway, which runs along a 665km line through 20 stations across Selangor, Pahang, Terengganu and Kelantan, aims to improve domestic connectivity for both passengers and goods.

The project is expected to boost tourism on the rail-underserved east coast and alleviate crippling congestion on the highways leading there during festive periods.

It will also create a land connection for transporting goods from the western Port Klang to Kuantan Port on the east coast and vice versa, aimed at giving investors and businesses more export options when setting up base at the numerous industrial parks anywhere along the line.

The ECRL also has the potential to shake up regional shipping routes, by allowing goods to get from the Malacca Strait to the South China Sea by land instead of sailing through the congested lanes around Singapore.

This could potentially cut journey times by around a day and divert lucrative shipping traffic away from the established maritime hub in the city-state.

And if the ECRL can overcome technical and geopolitical challenges to be connected to Thailand’s rail network, it will give goods and passengers another option of crossing into Malaysia’s northern neighbour and beyond to China, and become the centrepiece of a pan-Asia railway, something Beijing has already said it would consider facilitating.

During his three-day official visit to Malaysia last June, Chinese Premier Li Qiang said Beijing was willing to study a plan to connect the ECRL to other China-backed railway projects in Laos and Thailand, without offering further details.

Nor Aziati Abdul Hamid, senior researcher at Universiti Tun Hussein Onn's Industry Centre of Excellence for Railway, called the ECRL’s potential connection with Thailand an “ambitious vision” that would significantly improve connectivity between Malaysia and the broader Southeast Asia.

“However, this goal faces several challenges that need to be addressed for it to become a reality. These challenges are both technical and geopolitical, spanning across infrastructure, logistics, regulatory frameworks and international cooperation,” she told CNA.

PASSENGER CONNECTIVITY

Domestically, Nor Aziati believes the ECRL will “significantly enhance” passenger connectivity in peninsular Malaysia, pointing out that the train can run at speeds of up to 160kmh.

“Many towns that are poorly connected by the current rail system will now have better access via the ECRL, opening up new travel patterns and increasing ridership,” she said.

Furthermore, bus, rail and flight services to the east coast typically see “a surge in demand” during holiday seasons such as Hari Raya Puasa and Hari Raya Haji, when many Malaysians travel back to their hometowns and bus tickets often sell out weeks in advance, Nor Aziati noted.

Those who choose to drive back will have to slog it out on massively congested highways such as the Karak Expressway and the East Coast Expressway, with travelling times of 10 to 12 hours or more, she said.

Nor Aziati said that the current KTM network serving the east coast, often called the “Jungle Line” as it passes through forests in the deep interior, uses “outdated” infrastructure with lower train speeds and frequencies.

“KTM's services have been seen more as an option for leisurely or budget travel rather than fast, business-oriented or time-sensitive trips,” she added, suggesting that the ECRL will be “far superior” in terms of travel time, efficiency and frequency.

The ECRL’s passenger service will use six-carriage electric trains that can carry 430 passengers.

An event to unveil the train’s design on Dec 18 suggested that cabins would be wheelchair-friendly and equipped with fast internet speeds, while a promotional video showed off interiors with swivelling seats and prayer rooms.

Despite that, transport consultant Rosli Azad Khan cautioned that the ECRL would not be able to maintain consistent speeds of 160kmh given its single-track design, which means trains going in either direction use the same track.

“Running train services on a single-track rail is very challenging, as each train must stop at passing loop stations multiple times along the route to allow for trains coming from the opposite direction,” he told CNA.

“Delays will be inevitable and will be a frequent issue.”

In November 2023, ECRL owner Malaysia Rail Link (MRL) told local media that the network will have seven passing loops - in addition to those at stations - to allow trains to bypass each other.

The ECRL’s original alignment had featured a fully double-track design, but cost-cutting measures by the then-government in 2019 when resuming the project meant double-tracking was deferred. It could still be introduced depending on future demand.

Experts had concluded then that the single-track design could pose operational and safety challenges for the ECRL, including a lack of an alternative track during maintenance and increased risk of head-on collisions, the Star reported.

Rosli also believes the ECRL will serve areas where travel demand is “much lower”, such as Kuantan and Kuala Terengganu.

“Therefore, it can be expected that train departures will be less frequent, further reducing inter-town travel demand. It would be challenging for the ECRL to capture this segment of the travel market,” he added.

Muhammad Asyraf Mohd Nor, who lives in Gebeng near Kuantan, said he usually takes a bus when going back to his hometown in Gombak for the weekend. The 33-year-old, who works as a surveyor, said it is too tiring to make the drive after a long week at work.

“I have thought of taking the ECRL once it is ready. But I think tickets will be expensive. If prices are too high, I will still take the bus,” he told CNA.

However, the fact that the ECRL operates at a medium speed of 160kmh, as opposed to a high-speed rail’s 250kmh and above, means its tickets could be priced affordably and cater to a broader segment of the population, said Nor Aziati from Universiti Tun Hussein Onn.

“Higher speeds require more energy and maintenance, potentially leading to higher operating costs, which would need to be passed on to consumers in the form of higher fares,” she said.

“For many passengers, especially those travelling regularly or for family visits, affordability is often more important than shaving off an additional hour from the journey time.”

East Coast Economic Region Development Council chief operating officer Ragu Sampasivam, who was involved in the initial feasibility studies for the ECRL, said government agencies are exploring the idea of family tickets that will allow passengers to hop on and off at any station.

“We would like to price (tickets) in such a way that it becomes appealing for people to use it. And to me, as long as I don't lose money in operating, it's fine,” he told CNA.

“Once you start filling (up the train), more people use it, then let's talk about profit later. Let it get traction.”

The East Coast Economic Region Development Council statutory body was established to spearhead the socioeconomic development of the East Coast Economic Region.

Another prospect of raising passenger numbers on the ECRL is by connecting it directly with the unconfirmed Kuala Lumpur-Singapore high-speed rail (HSR), but Rosli said this would not make sense given the likely different fares and target markets for the two networks.

Rosli predicted that passengers travelling by HSR from the south would be considered more upmarket, in the same category as air travellers, while those who take the ECRL would be considered at the mid to low-end, equivalent to bus passengers or car users.

“ECRL is much slower in speed, so the upmarket sector travellers will more likely travel by air to places like Kota Bharu or Kuala Terengganu. They won't take the ECRL,” he said.

“Similarly, the mid to low-end market travellers will not be taking HSR as the fares will be beyond their reach; they will continue to travel by the KTM electric train service to Johor Bahru or go by bus.”

The 350km HSR between Kuala Lumpur and Singapore was first proposed in 2013, and a binding agreement was inked in December 2016 to have the line operational by 2026.

It was discontinued after multiple postponements at Malaysia's request and the agreement lapsed in December 2020, with Malaysia paying more than S$102 million (US$75 million) in compensation to Singapore for the termination.

Talk of resurrecting the project - which aims to reduce travel time between Kuala Lumpur and Singapore to 90 minutes from more than four hours by car - gained momentum after current prime minister Anwar Ibrahim took power in November 2022.

Most recently, Malaysia has estimated the project would cost RM100 billion (US$22.5 billion) today and the government has said funding would have to come totally from the private sector.

Malaysia has shortlisted three out of seven consortiums that submitted proposals on the HSR, while Singapore has said it is open to fresh proposals with negotiations starting from a clean slate.

Rosli also pointed out that it would be costly to connect the HSR, which he said if revived is likely to terminate in the heart of Kuala Lumpur at the glitzy Tun Razak Exchange (TRX), with the ECRL’s Gombak station, the nearest to Kuala Lumpur city centre.

“That would be a very expensive exercise as it goes through some very prime areas of KL,” he said, noting existing connections between Kuala Lumpur and Gombak via the Light Rapid Transit line.

“To go to Gombak from TRX is quite tricky as most of the route or alignment has been fully developed and built.”

FREIGHT CONNECTIVITY

Authorities have said they expect passenger services to make up 30 per cent of the ECRL’s operational revenue, with the remaining 70 per cent coming from the transportation of goods.

Sampasivam said this projection came about after his team found that industrial businesses were keen on having a more efficient option for moving their goods around.

“We feel that it allows investors who come to the east coast or the west coast to have this two-port option,” he said, noting that businesses who want to ship out their goods to East Asia or the Middle East and Europe can do it from Kuantan Port and Port Klang respectively.

“So that's how we feel the efficiency and positioning of these ports can also be improved.”

Construction of the ECRL’s extension from Gombak to Port Klang will be completed in December 2027, with services starting in January 2028. For freight, an electric locomotive will pull box car and container flatbed wagons at speeds of up to 80kmh.

But Federation of Malaysian Freight Forwarders president Tony Chia said it is difficult to talk about whether logistics players will use the ECRL when details about its services remain “scant”.

These include freight costs, schedules and frequencies, transit time per trip, last-mile transport availability, as well as charges for loading on and off, he told CNA.

“Also, the ECRL does not extend to the berths and there would be (a need to) to offload the containers into the container yard and then reload to send to ship,” he said.

Last June, Transport Minister Anthony Loke urged companies to plan ahead and start discussions with MRL to get better freight rates on the ECRL, citing how car manufacturer Perodua has signed an agreement to explore how the new railway can diversify how its products are transported.

The aim is for Perodua to move its automotive parts from its hub in Serendah, Selangor to the east coast and back using the ECRL.

MRL has also signed a memorandum of understanding (MOU) with Kuantan Port and Port Klang’s Northport to improve integration and efficiency in the way the ECRL transports goods between the two ports.

Sampasivam said the MOU will explore “end-to-end facilitation”, referring to how ships can load and unload goods directly on and off freight wagons at both ports.

"This crucial last-mile connectivity between Kuantan Port and Port Klang will streamline the transfer of goods between ports and address the issue of double-handling of cargo,” MRL chief executive officer Darwis Abdul Razak said during the MOU signing.

CHEAPER, FASTER AND GREENER?

Logistics trainer AS Oei, who has more than five decades of experience working in the port and logistics sector, said freighters could use the ECRL to move goods from the east coast states of Kelantan and Terengganu to Port Klang.

“At the moment, both these states are exporting palm oil for overseas shipments via Port Klang,” he told CNA.

“The product is being transported by road which is much more expensive than by rail, that is if the ECRL operator wants to offer competitive rates to the industry.”

Loke, the transport minister, had also warned that the government is using a “carrot and stick” approach by providing incentives to get companies to use the ECRL as their main mode of transportation.

If these incentives do not generate enough interest, he reportedly said the government could tighten road transportation rules, particularly for heavy vehicles, to reduce the number of such vehicles on highways such as the Karak Highway.

The ECRL is expected to take around four to five hours to transport goods from Port Klang to Kuantan Port, which is slightly faster than going by road through the Karak Highway towards the east coast, according to the Federation of Malaysian Freight Forwarders’ Chia.

Sampasivam said the ECRL will also provide a ready-made environmentally friendly option for heavy industrial players that frequently move their products.

This includes national oil company Petronas, which currently has “quite a number of lorries flying” between its Kerteh hub in Terengganu and Kuantan Port to transport chemical products, he said.

“You also have Alliance Steel near Kuantan Port at the industrial area in Gebeng. If they want to ship their products to the west coast, what better way than just put them on the rail,” he added.

“You can take thousands of lorries off the road and reduce your carbon footprint.”

Chin Chee Unn, who runs a car workshop near the planned ECRL station in Pahang’s Temerloh industrial area, said he currently uses lorries to transport automotive parts and might consider using the ECRL as a quicker and more efficient option.

“I have also seen a number of storage warehouses in this area being rented by big players like (e-commerce giant) Shopee,” he told CNA.

“They will probably use the ECRL as a faster way of (locally) distributing their products from here.”

Chia from the Federation of Malaysian Freight Forwarders said the current trucking volume between Port Klang and Kuantan Port is not “significant”, noting that most are for local orders and consumption rather than port-to-port transit cargo.

“With uncertainty surrounding the implementation and running of ECRL, it may be premature to discuss the impact of ECRL connecting Port Klang and Kuantan on regional and international shipping routes,” he said.

“A fact is that ships will call where there is sufficient cargo for them … The final decision on shipping routes will rest with shipping lines.”

BYPASSING SINGAPORE?

With shipping routes from Kuantan Port linking directly to Shenzhen in China, a new sea-land-sea route offered by the ECRL could potentially allow exporters to bypass Singapore in reaching major markets in Asia and beyond, wrote Qarrem Kassim, analyst at Malaysia’s Institute of Strategic and International Studies in the January/March 2024 edition of East Asian Policy.

While the ECRL route is expected to entail higher shipping costs, roughly 12 per cent more than a purely sea-based route, estimates suggest it could reduce travel time by 18 per cent or up to 30 hours for goods to get from Port Klang to Shenzhen, he said.

This is ideal for time-sensitive goods like pharmaceutical ingredients and agrofood products, Qarrem said.

“Nevertheless, while some trade may be expected to be diverted, the degree to which the ECRL could pose a threat to Singapore’s position depends on the efficiency of the transit of goods,” he added.

The ECRL can also help logistics players improve risk management by not sending all their goods through the congested Malacca Strait via Singapore, said Marco Tieman, chief executive officer of supply chain strategy consultancy LBB International.

Despite that, G Durairaj, managing director of maritime and logistics consultancy PortsWorld, said he does not foresee the port of Singapore - renowned for its handling efficiency and maritime services - losing business because of the ECRL.

Durairaj told CNA it is a misperception that it is expensive to push goods through Singapore’s port, noting that the port handles tremendous volume and can thus offer transshipment costs that are “much cheaper” than Malaysia.

“Singapore is not going to just clap its hands … I think they may have a strategy on how to fight (the ECRL),” he said, noting that with its volume the Singapore port could offer even lower rates.

Transshipment refers to the transfer of cargo from one vessel to another while goods are in transit, typically at an intermediate port or anchorage. Shipping companies do this to optimise routes and costs.

Singapore is the world’s largest transshipment hub and the second busiest port in the world behind Shanghai, handling more than 40 million 20-foot equivalent unit (TEU) containers in 2024.

In contrast, Port Klang handled 14 million TEUs in 2023, with transshipment cargo comprising about seven million TEUs, Durairaj said.

Chia said the ECRL, if proven to be a viable option, could be used to reposition empty containers from Port Klang to Kuantan Port.

The repositioning of containers is usually done from a port that imports more than it exports to another one that deals more in exports, a scenario that could describe the situation at Port Klang and Kuantan Port.

Empty containers could also be moved to ports that offer cheaper storage costs. This also means it is often more cost-effective for carriers to move empty containers than to incur extra fees while waiting for them to be filled.

But with the advent of e-commerce, Durairaj noted that a lot of containers currently being shipped are less-than-container load, using a term for containers filled with goods meant for different customers and destinations.

This is as opposed to full-container load, or the one container, one customer market the ECRL could have been targeting when it was touted as an alternative land connection for transshipment, he said.

“The question for the ECRL is: Where is the volume going to come from?” Durairaj asked.

“You need to look at new sources of cargo that are going to China or markets beyond in East Asia. The volume may be there, but then again, what kind of cargo? A lot of them are less-than-container load.”

Sampasivam of the East Coast Economic Region Development Council played down the ECRL’s potential of diverting transshipment traffic away from Singapore, insisting that its aim is to allow businesses along the railway to have access to both Port Klang and Kuantan Port.

“It all depends on the type of goods, where they are going, and whether they have to go through Singapore. Because when all is said and done, Singapore has got one of the best connectivity to the world’s ports,” he said.

Ultimately, Tieman said the ECRL is still a more viable option than Thailand’s proposed land bridge, which aims to connect the Indian and Pacific Oceans and bypass one of the world’s busiest shipping lanes.

Thailand’s plan is to connect two deep sea ports on its eastern and western coasts using a rail and road system. The eastern port will be located in Chumphon province on the Gulf of Thailand and the other in Ranong province on the Andaman Sea.

Like the ECRL, the Thai land bridge could also divert traffic away from Singapore and save shipping companies considerable time. But unlike the ECRL, Thailand’s plan has made little progress, analysts say.

“Thailand has been talking about the land bridge for so long,” Tieman said, noting that the project would leave significant environmental impact in the southern part of the country and “wipe out” important tourism dollars.

“There is no existing port on the west side of Thailand. Malaysia just has made it happen with this rail link between two existing ports.”

CONNECTING ECRL TO THAILAND

Malaysia’s transport minister Loke, however, has proposed connecting the ECRL to Thailand’s rail network through Rantau Panjang in Kelantan as an alternative to Bangkok’s land bridge.

“If that were to materialise, the ECRL would be able to tap into Thailand’s entire rail network and link with Kunming, in Southwestern China, via Laos, achieving greater free flow of goods and passengers within the region,” he said at the event on Dec 18.

Jaafar Ismail, owner of Fergana Capital Ventures told CNA that Malaysia would benefit from connecting the ECRL to Thailand.

“The key route that's advantageous to the ECRL will be connecting the west coast of Malaysia’s peninsula to the east coast of southern Thailand, which is where industrial Thailand will grow going forward,” he said.

China, which has financed most of the ECRL’s construction under its Belt and Road Initiative, has said it is willing to study a plan to connect the ECRL to Thailand and Laos, potentially expanding the initiative across Southeast Asia.

This proposal would make the central line of a proposed pan-Asia railway a reality, the Chinese Premier Li Qiang said during his official visit to Malaysia.

“By positioning the ECRL as a central component of a pan-Asia railway, China envisions a comprehensive transportation network that would facilitate trade, investment, and cultural exchanges among countries along the route,” said Universiti Tun Hussein Onn’s Nor Aziati.

But there are significant engineering challenges to this plan, not least the fact that the ECRL and Thailand’s railway use different types of railway tracks. The ECRL uses a wider standard gauge track, while the latter uses a metre gauge track, like Malaysia’s current KTM network.

“This difference in configuration will require different train sets to operate. The likelihood of the State Railway of Thailand or KTM switching to standard gauge in the foreseeable future is low, possibly in 50 years or more,” transport consultant Rosli said.