Jobs, profits, kidnappings: Bright-eyed jobseekers bet fortunes on lucrative offshore casino work in the Philippines

Despite the economic returns, Philippine lawmakers are wary of what they say are the social costs of these online casinos, which have been linked to multiple crimes, including human trafficking.

Vietnamese trainees attend Chinese lessons before travelling to work in the Philippines' offshore gambling operators, also known as POGOs. (CNA/Tung Ngo)

MANILA/HANOI: Promises of high wages, employment benefits, and low entry requirements have enticed many from regional countries to travel to the Philippines to join Asia’s biggest online gambling hub.

Philippine Offshore Gaming Operators, often referred to by their acronym POGOs, are virtual casino firms that operate in the archipelago but cater to overseas customers.

These online casinos contribute sizable economic benefits to the country, but are part of a controversial industry facing backlash for its social ills.

The sector is also dealing with a spate of crime and scandals including kidnapping, trafficking, assault and scams.

The betting platforms flourished in the past two decades due to the Philippines’ liberal gambling laws. They have a huge customer base in China, where gambling is illegal.

The industry reportedly hired more than 300,000 Chinese workers at its peak, before the COVID-19 pandemic struck.

“Many Chinese nationals had to return to China. (Also,) China does not encourage its citizens to go to the Philippines to work at POGOs,” said Ms Do Thi Kim, the owner of a human resource agency recruiting for the offshore operators.

“Therefore, the firms are hugely in need of workers to solve their labour shortage.”

Neighbouring Vietnam, with its young and growing population, has emerged as a major source of workers for the digital casinos.

A network of recruiters and training centres have sprouted up in the country in recent years, reaching far into rural areas to tempt jobseekers in search of a better life.

VIETNAM’S RECRUITS

Mr Chao Lao Ta, 21, was born and raised in the remote region of the northern Vietnamese commune of Bat Xat in Lao Cai province, near the border with China.

He hails from the Dao ethnic minority, who, for generations, have relied on terrace farming for food and income.

Mr Ta said he wants to leave that tradition, and a life of hardship and poverty, behind.

“The work here is very hard. If it's a bad harvest, it's extremely difficult. Even my family will not have enough food,” he said.

When the lure of the online gambling industry reached his hometown, Mr Ta decided to travel to the Philippines to join the sector in hopes of earning a substantial income.

“(Bat Xat) is where home is, but I can't make enough here. I must find a different path that I hope can change my life,” Mr Ta said.

“The Philippine market is emerging as a good market with potential, and it seems quite stable.”

But first, Mr Ta had to learn to speak Mandarin, as the jobs at POGOs usually involve chatting with Chinese gamblers virtually, and helping them with money transfers for their accounts.

TOUGH ROAD TO PHILIPPINES

With an increasing appetite among locals to work at the cyber gambling dens, training centres have popped up to tap the lucrative business in preparing prospective recruits.

Trainees are taught computer and language skills over six months, before they are shipped off to the Philippines.

However, courses at these centres can cost a fortune.

Mr Ta’s father is the village chief, and earns some extra income. Even so, the family had to borrow nearly US$3,000 to pay for Mr Ta’s training.

The family said they are betting on him to turn their fortunes around.

“Most of our young people cannot find jobs after high school. My family's income for a whole year is less than US$1,600. (My son) would earn that much in a month (in the Philippines),” said his father, Mr Chao O Pet.

Workers are promised a monthly salary of up to US$1,700 to work at the online casinos. The amount is up to four times what they are likely to earn in Vietnam, and does not require a college degree or manual labour.

Recruitment agencies use social media to reach out to potential recruits, touting high salaries, free meals and accommodation, and fancy offices in skyscrapers.

It is a stark contrast to life in rural Vietnam, where many trainees like Mr Ta are from.

“My goal is to make enough money in the first six months to pay off my family's debts. I also hope I can make money to send my younger brother to college,” Mr Ta said.

LIFE IN POGOS

Mr Ta was recruited by a Hanoi-based agency for a POGO job in Cavite province, some 30km southwest of Philippines’ capital Manila.

Along with a dozen other new hires, they entered the Philippines as tourists. The recruitment agency told the group that they should not have issues getting past immigration, but if they did, the company would handle it.

The operators would only arrange for work visas after the workers began their jobs.

During his employment with an online casino, Mr Ta lived and worked in a heavily-guarded compound, which was converted from a resort and occupies an entire island. Foreign workers have their own living quarters near their office building.

“It has been almost three months since I started working here, but I am still learning about the work. There are many new rules about casino games that I have not fully understood,” he said.

“The hardest part was the night shift as I could not open my eyes. I will be promoted next month to a key customer service agent and I will be able to train newcomers as well.”

In recent years, there is a visible multiplier effect stemming from the establishment of POGOs in the area. A number of businesses in the vicinity now specially cater to a Chinese clientele.

But despite the economic returns, Philippine lawmakers are wary of what they say are the social costs of these online casinos, which have been linked to multiple crimes, including human trafficking.

CRIME LINKS TO POGOS

Mia (not her real name) was only 15 years old, when she was trafficked into a prostitution den that catered mostly to Chinese nationals in the Philippines.

Fearing that the syndicates who victimised her would track her down, she asked CNA not to reveal her real name.

“That time, my family was very poor. A friend offered me a job, saying it came with a huge salary,” Mia recounted. “They said I would be a massage therapist. But when I got there, I learnt I needed to provide extra services and have sex with customers.”

“That was the worst thing that happened to me. One man threatened to hurt me if I didn’t do what he wanted. There were some who would make me do acts I really couldn’t make myself do. I said no. He would offer money, but I really couldn’t do what he wanted,” she said.

At the prostitution ring that duped her, there were other victims, including a girl as young as 13 years old, Mia said.

In 2020, such prostitution dens became the subject of a Philippine Senate panel investigation.

Opposition Senator Risa Hontiveros uncovered a trafficking scheme that offered sexual services to POGO workers. She subsequently called for the suspension of all offshore gaming operations, saying they “attract criminals into (the) country”.

Aside from prostitution, the POGOs have been linked to other crimes. There are allegations of violence among POGO factions. Dead bodies of Chinese nationals have been discovered in abandoned lots, and suspected kidnappers found to possess unlicensed firearms.

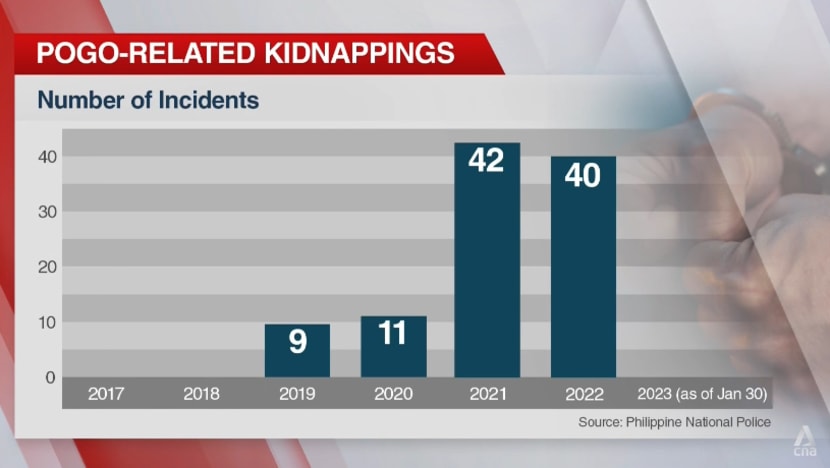

Police data shows that 40 POGO-related kidnapping incidents were recorded in 2022. While the number is slightly lower than the 42 recorded a year before, it is still at least four times higher compared to pre-pandemic levels.

Of the 892 suspects investigated in these incidents, 782 individuals – 87 per cent – were Chinese nationals.

SPATE OF KIDNAPPINGS

In the past two years, foreign workers became valued commodities, as labour grew scarce due to pandemic-linked travel restrictions. This led to an alleged wave of kidnapping incidents of migrant workers.

A police source, who requested not to be identified, gave CNA details of a case involving the recent escape of an abducted Chinese POGO worker.

The source said abductors demanded at gunpoint 300,000 Philippine pesos (US$5,500) for the worker’s release – a ransom amount similar to other POGO-linked kidnapping incidents.

At the bayside area in Pasay City where the suspected abductors were arrested, CNA tracked down several witnesses.

They said that the Chinese POGO worker jumped out of a parked vehicle on a bridge just metres away from malls, condominiums, offices, and the Senate building.

A local who helped call the police after the worker fled the vehicle, said: "I comforted her. I ensured she was telling the truth. She shivered, cried. Her eyes were swollen. She was afraid and said she was kidnapped. She typed, ‘Kidnap. Help me, help me.’ (on her phone).”

Multiple witnesses’ statements of the abducted worker’s escape were consistent.

The prevailing perception among witnesses that CNA spoke to is that the syndicate, or syndicates, behind these abductions are people with the resources to put their lives at risk. So, many victims and witnesses are forced to stay silent.

CALL FOR ACTION AGAINST ILLEGAL POGOS

The Philippines is host to more than 30 legally registered POGOs as of February this year. However, many more remain unlicensed and operate illegally.

Still, proponents of the industry said one should distinguish between legal and illegal companies.

Registered businesses are regulated by a state firm in charge of casinos and gaming, and the industry is among the government's largest revenue sources.

An industry group stressed the economic benefits of the sector, saying it contributed over US$1.12 billion to the government from 2016 to 2022, while providing more than 23,000 jobs.

It added that no crimes were recorded among its 16 member operators.

“It is sad that due to unfortunate incidents, criticisms hastily generalise POGOs,” said Mr Paul Bongco, a spokesperson for the association of service providers and POGOs.

Philippine Senator Grace Poe, who is pushing for the cessation of these virtual offshore casinos, said it is difficult to distinguish between legal and illegal companies.

Furthermore, the negative consequences of these cyber gambling dens overwhelmingly outweigh the benefits, she said.

Ms Poe is the daughter of late action star Fernando Poe Jr., who is known in his movies as a defender of the oppressed.

These days, his daughter is fighting crime through her legislative work.

“This sector has turned one vice, which is gambling, into a host of more serious problems like kidnapping, serious physical injuries, and human trafficking,” Ms Poe said.

With the rise of POGO-linked crimes, Filipino-Chinese business groups are also calling on the government to take decisive action on illegal or unlicensed operations.

“The Federation hopes the government of the Philippines can assess the whole situation and decide based on balancing interest,” said Mr Wilson Lee Flores, a board member at the Federation of Filipino Chinese Chambers of Commerce and Industry (FFCCCII).

“Most of the operators of POGOs in the Philippines are illegal entrepreneurs of China. We don't want the Philippines to be known in China, and all of Asia, as the playground or the haven for illegal entrepreneurs,” he said.

Of Metro Manila’s 16 cities, at least one has banned POGOs. Pasig City’s ordinance will ban all forms of online gaming to operate in the city after 2023, citing the spate of POGO-related kidnappings.

ISSUES EXTEND BEYOND POGOS

But beyond the kidnappings, syndicates have started taking advantage of the perceived lucrativeness of the online gambling hub, using fake POGO jobs as a lure to recruit Filipinos into scam jobs.

Jane (not her real name), a trafficking survivor, was employed to work as a POGO call centre operator in Thailand, but ended up a victim who was forced to work in a cryptocurrency scam ring based in Myanmar. She asked CNA not to reveal her real name.

“I heard (from my recruiter) the word ‘POGO’. I searched (online). I saw an ad for a POGO job with 50,000 pesos (US$907) monthly salary. I saw ads and videos urging Filipinos (to take up POGO jobs) because of high salaries and low stress),” she said.

A representative from the Philippine Bureau of Immigration said many Filipinos who were duped into these job scams are highly educated, and have previous international travel records. This makes it harder for immigration officials to identify them as trafficking victims.

“They are enticed by these companies to work abroad with high salaries, with good promises about the company … only to find out that it's a cryptocurrency scam,” said the bureau’s spokesperson Dana Sandoval.

She added that victims are often subjected to physical abuse, especially if they fail to meet their quota to scam others.

Jane now spends her days debunking online fake POGO job ads on a social media page that once connected her to her illegal recruiter.

“The only advice I can give is to warn those who plan to apply for such jobs not to do it... Our days were hard (in Myanmar), doing acts we were forced to do. We had no choice. We needed to survive,” she said.

But despite the pitfalls, the POGO industry continues to be a lure for many young people in Vietnam and around the region, who are willing to bet on their luck for a better future.

“I think there will be more Vietnamese heading to work at POGOs over the next few years. Because of the high demand, (and) it's easy to send workers to the Philippines currently,” said recruiter Ms Kim.