Thailand Election 2026: Can Anutin ride nationalism wave and lead Bhumjaithai to victory?

CNA visits the crucial electoral battleground of Thailand’s northeast region to gauge the mood ahead of Sunday’s (Feb 8) vote and speaks to PM Anutin Charnvirakul on the campaign trail.

Anutin Charnvirakul on the campaign trail in Ubon Ratchathani ahead of the 2026 Thai election on Jan 27, 2026. (Photo: CNA/Jack Board)

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

UBON RATCHATHANI, Thailand: On the dusty outskirts of Ubon Ratchathani, a north-eastern city near the borders with Cambodia and Laos, a small, curious crowd gathers around a fresh market.

They are here to catch a glimpse of, or to take a selfie with, a man who for many years was simply the leader of a mid-sized regional political party called Bhumjaithai.

That man now steps out from a convoy of vehicles as prime minister.

Anutin Charnvirakul slowly weaves through the throng, stopping to greet bright-eyed senior citizens and giggling students. He tries slices of fruit proffered to him and buys iced drinks for his entourage.

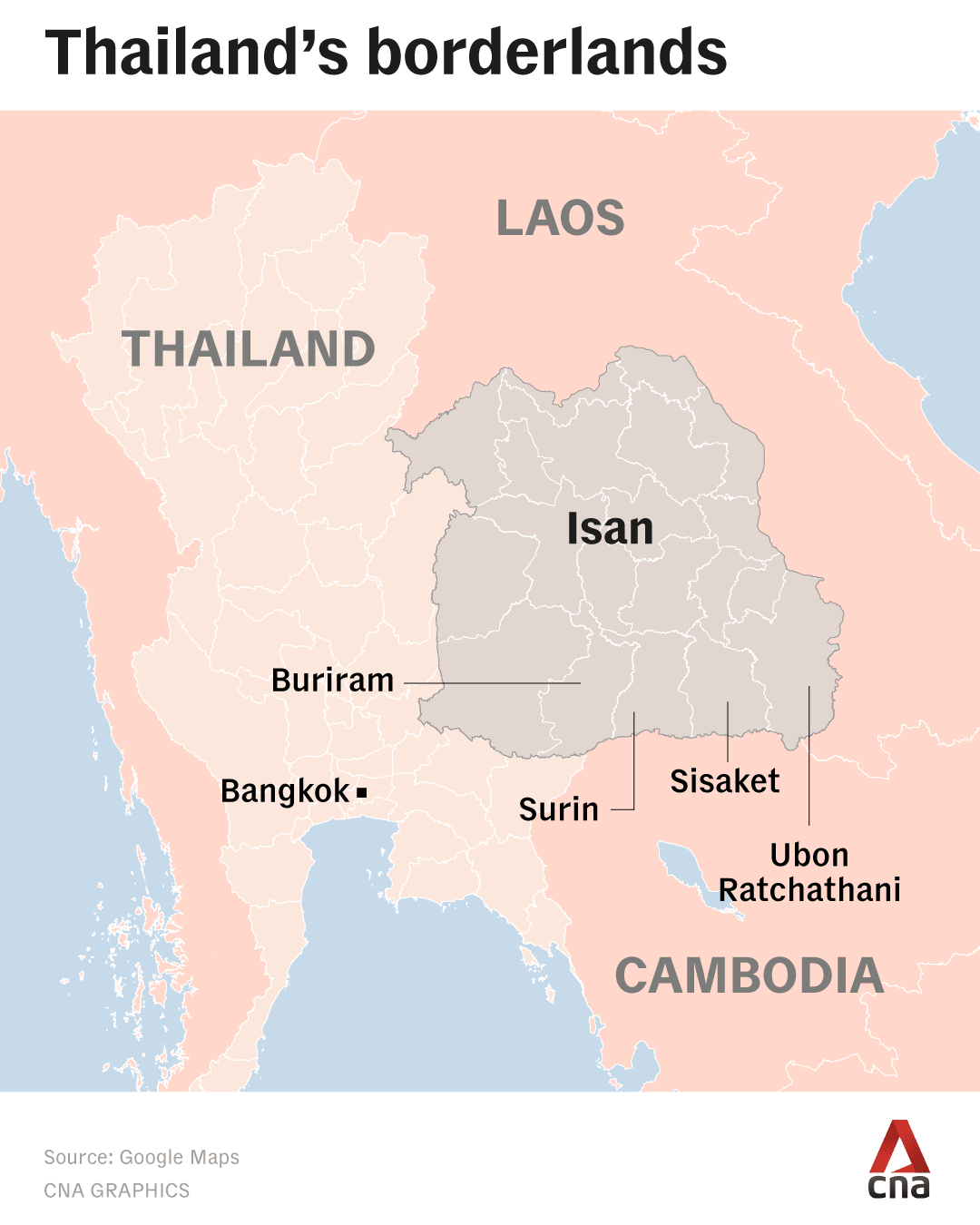

The former health and interior minister has made visiting the Isan region, a broad expanse of 20 rural and typically poorer provinces, a key priority since he was elevated to national leadership in September 2025.

Ubon Ratchathani is not traditional Bhumjaithai turf, but it is part of the northeastern belt that Anutin is sharply targeting to grow the party from a regional powerplayer into a national force.

In the market, as he stops to speak with CNA, it is clear he is confident about that mission in the days ahead of the upcoming vote this Sunday (Feb 8).

“I have to say, we aim high. I think we will be able to gain trust and confidence from our voters,” he said.

“We understand what Thai people need. We understand how to handle a system that works in Thailand, we have so many professionals who join us to bring Thailand forward,” he said.

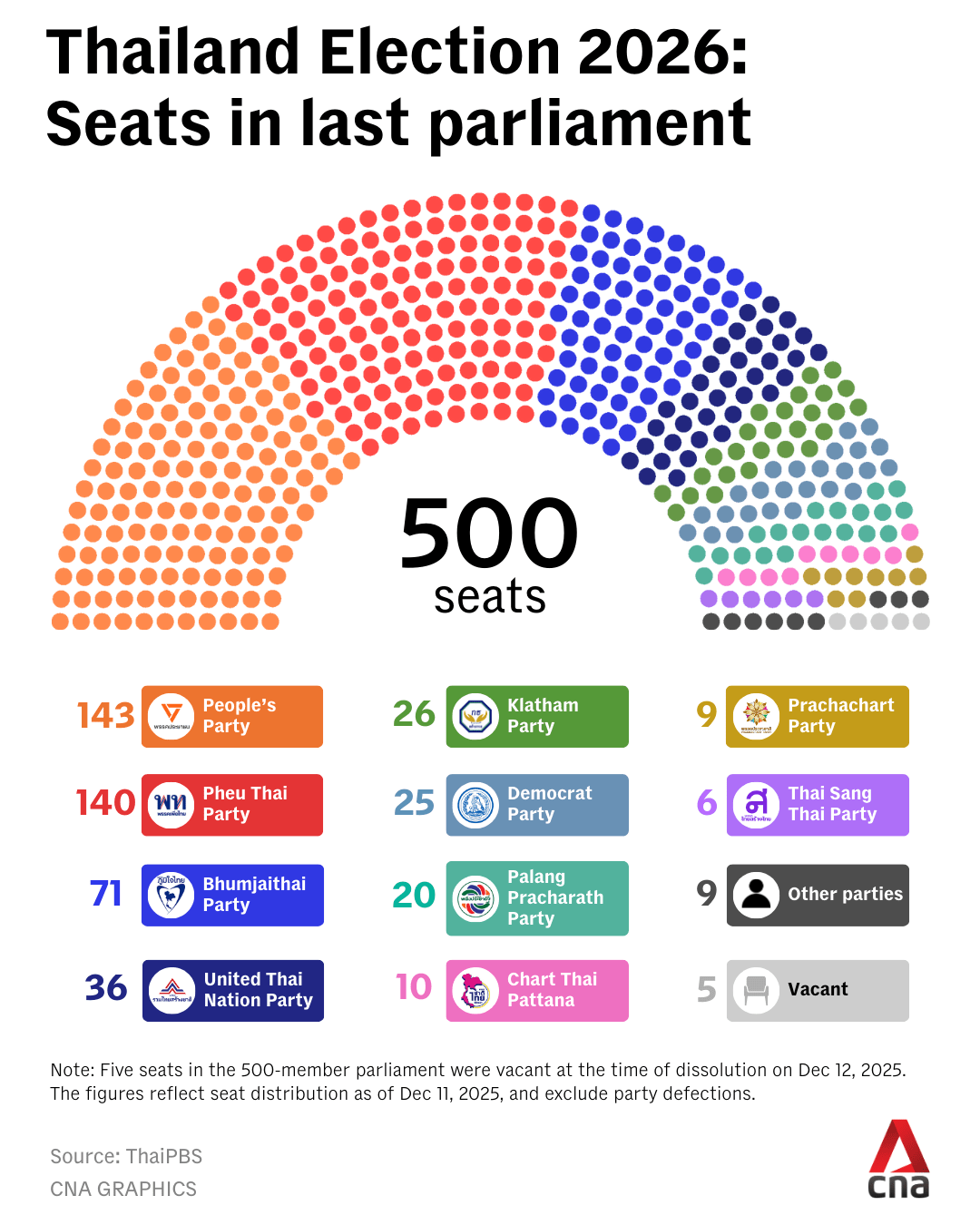

Following the disqualification of then-prime minister Paetongtarn Shinawatra last August amid an ethics violation scandal, Anutin cobbled together support from opposition and coalition partners to form a majority bloc in parliament and was appointed prime minister the following month.

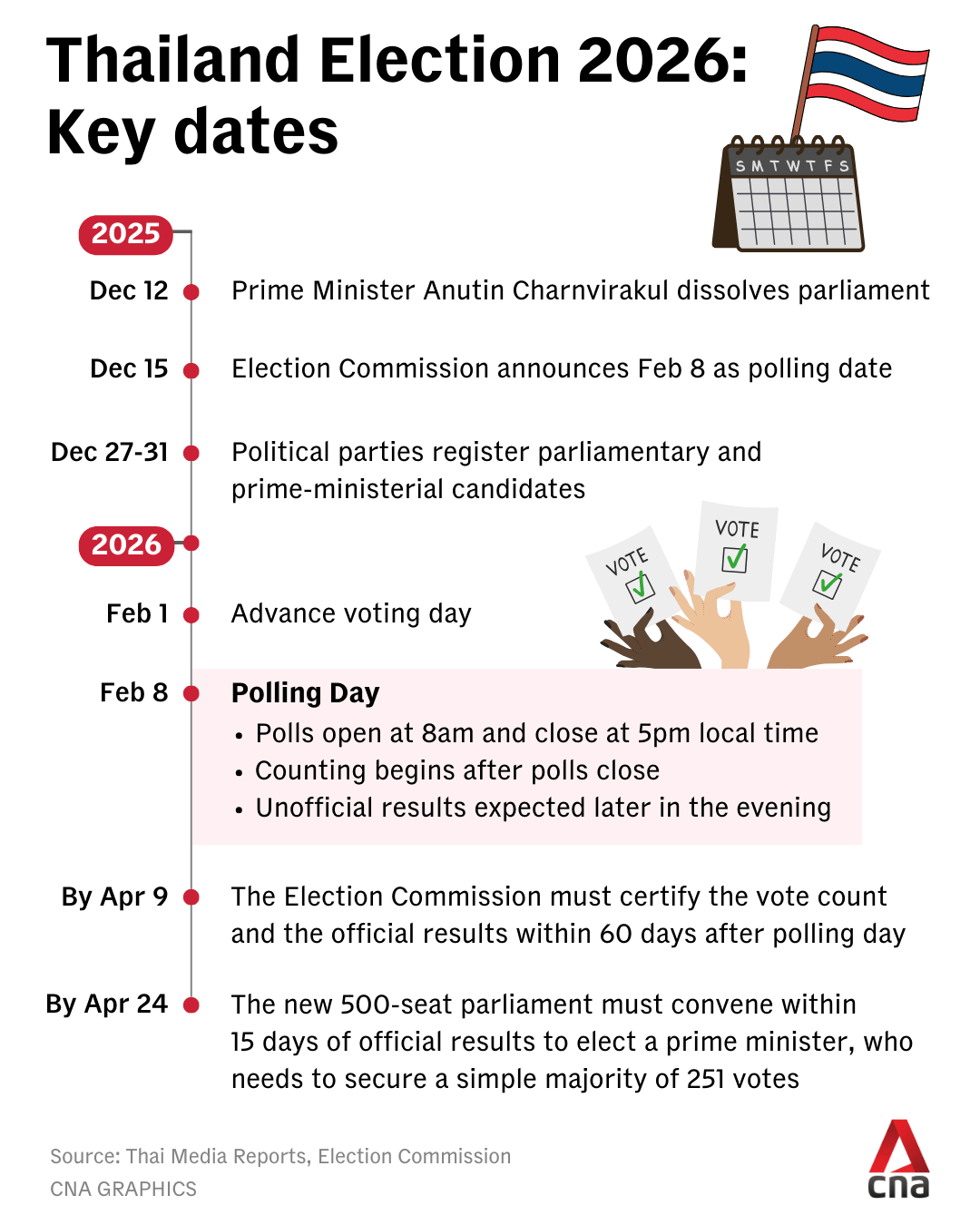

He later dissolved parliament on Dec 12, becoming caretaker leader ahead of the snap election scheduled later this week.

What happens in Isan could help swing the election, analysts say. Thailand's largest electoral region is in flux, politically and economically.

“Isan is the only area where you have a clear three parties fighting. It's a war of the three gangs,” said Pitch Pongsawat, a professor of political science at Chulalongkorn University.

The region comprises 20 of Thailand’s 77 provinces and accounts for 133 constituency seats out of 400 total in the country’s House of Representatives.

Bhumjaithai is in an electoral tussle with the longtime custodians of Isan, the Pheu Thai Party, which continues “to gain a lot of loyalty with some big families and with their big dream of economic prosperity” for rural Thais, Pitch said, along with the disruptive force of the People’s Party, promising to reform politics and fight corruption.

The contest is expected to be tight. Bhumjaithai was polling third in the region with 27.2 per cent support, according to a survey conducted by the University of Khon Kaen in January.

Pheu Thai was polling at 30.1 per cent, slightly behind the national frontrunner, the reformist People's Party at 30.3 per cent.

Yet with the prevailing dynamics of the region, defined by the uncertainty and disruption of a conflict with neighbouring Cambodia, analysts say Anutin’s regional party could soon have a much larger electoral footprint after the vote.

THE CAMBODIA EFFECT

From the market, Anutin travels back in his convoy to another voting district outside the city.

The sun sets in violent orange hues as he takes to the stage in front of more than a thousand locals, music blaring the party’s theme song as keen attendees wave cardboard signs promoting a local member of parliament candidate.

His speech is at times languid and joking; at others fiery and bombastic.

He drills down on nationalistic sentiments. The type that has stemmed from the borderlands and spread across the country in the wake of the uncertainty and disruption caused by the ongoing Cambodia border conflict.

Just a few hours south of here, fighting, particularly in July and December, forced thousands to flee on both sides and left more than 100 people dead.

Anutin talks, not for the first time, about building a border wall, a broader hardening of tone on security, tied into his campaign narrative of strength and protection for the nation.

“I don’t care what the other parties say. We are ready to fight. If they (Cambodia) fire one rocket, we will send back 100,” he said, to loud cheers.

The election, called less than 100 days into Anutin’s administration, may allow him to harness sentiments stirred by months of fighting across the border, said Stithorn Thananithichot, a senior research associate at Chulalongkorn University.

Anutin was already prime minister during the second round of major fighting, and was notably harder in tone than the previous Pheu Thai-led government, ruling out resuming negotiations with Cambodia to resolve the crisis and demanding that Phnom Penh meet a set of conditions set by Thailand for any cessation of hostilities.

It may have filtered through to the minds of voters, Stithorn said.

“Even those who used to vote for liberal or progressive parties before, with this feeling of the power of the nation, the nationalism, something came to their heart and their mind and this time they might vote because of this kind of emotion,” he said.

Bhumjaithai is best placed to benefit from such feelings, with Anutin cultivating strong relationships with the conservative royalist establishment and the military, Pitch said.

“They are good friends with the existing bureaucratic machine. They are good friends with the security forces and they are good friends with people who buy into the concept of conservative politics in Thailand,” he said.

In contrast, their main rivals face political drag over the Cambodia situation.

Pheu Thai has faced backlash for its role in managing the conflict - Paetongtarn was removed as prime minister over ethical violations linked to the issue involving a leaked phone call with former prime minister and current president of the senate Hun Sen - and the People’s Party pledging to reduce the role of the military in national affairs in the past.

Bhumjathai knows the border provinces, including Sisaket, Surin and Buriram, which have borne the brunt of the disruption, well.

They form the heartland of the party, which was founded in 2008 as a conservative-populist movement focused on local patronage and grassroots networks.

Over the years, it has drawn in existing powerful clans and influential families, and leans on local dynastic politics in various provinces, structured around the concept of a “Big House”, Pitch explained.

Gradually, the party has built influence from the heart of provinces, not from an ideological platform.

“We are definitely not left, we are right. We are very patriotic,” said Varawut Silpa-archa, a candidate for Bhumjaithai whose family has long been in Thai politics and has a stronghold in the central province of Suphan Buri.

Varawut, son of former prime minister Banharn Silpa-archa, recently switched allegiances for this election, having previously led the Chart Thai Pattana Party and served as a minister under different prime ministers.

Party line-ups are shifting with the times. Across the country, at least 91 lawmakers elected in 2023 have changed their political affiliation ahead of the polls, according to local media. Bhumjaithai has attracted 64 of them.

It is wise politics in rural areas, according to Somchai Srisutthiyakorn, Thailand’s former election commissioner.

“The local relationship with politicians matters more. Candidates, incumbent MPs, local power figures and even vote-buying are significant factors,” he said.

This strategy of building strong and deep provincial support - largely through tactical allymaking - in key areas also riding on a wave of patriotism has the party confident of building on its 2023 election results.

Back then it won the vast majority of seats in Buriram and Surin, while claiming key seats in closer contests in Sisaket and Ubon Ratchathani.

“This election is a new opportunity for people, as we are a medium-sized party. But in this round, we aim to become a larger party and to take the lead in forming the government,” said Jintawan Trisaranakul, a member of the last parliament and candidate for Bhumjaithai in Sisaket.

“People can be certain that he (Anutin) understands this area thoroughly. I think we can assure that the government truly understands our situation,” she said.

There is a larger question; whether nationalist campaigning delivers security and safety or is merely symbolism to win votes.

Some of those closer to the Cambodia frontier told CNA that they wonder if anyone really is paying attention to their current plight.

PEACE OR PROSPERITY

Not long after the fighting began close to the town of Nam Yuen in Ubon Ratchathani, thunder fell from the sky and into the home of Boonruam Thongwiset.

It was a missile launched from across the border. In a moment of fire and chaos, nearly everything he and his wife owned was lost.

“When it happened, I didn’t even feel afraid,” the 60 year-old said. “Seeing my house destroyed drained all my strength. I felt stunned and helpless.”

Half a year on, a new house for the couple is almost complete. Government funds were allocated to them for reconstruction; the replacement home is modern and more expansive than anything they had before.

But loss still lingers deeply and the couple are struggling. Even with a new roof, life has not returned to normal.

“I want to appeal to those in power to help restore our way of life. Right now, we only have a house. We don’t have the tools to earn a living. For example, I no longer have a freezer. I don’t have money to buy a new one,” he said, explaining that he used to make a living selling drinks and snacks.

“I’ve lost everything. All we can do now is wait for help from the government or other agencies, hoping they will show compassion to civilians affected by the war.”

In neighbouring Surin province, it is fear not loss that continues to grip farmer Vimol Kraseathep. She barely sleeps, always listening, always alert.

“If you ask whether it’s safe, it’s not. We have to stay alert all the time,” she said.

“If you ask how I feel, I don’t really know how to answer. We survived this time. We were lucky. But if next time it lands on us, that’s it.”

The 49-year-old said she would support Anutin’s plan for bolstered border defences. Without safety and peace, she said, no-one in the area can make a living. But she does not trust politicians.

“Big fish eat small fish,” she said.

That sense of neglect has helped locally-based parties gain traction along the border. They could do so again in Sunday’s poll.

Wasawat Poungponsri is the leader of Thai Ruam Palang Party, founded in 2021 in Ubon Ratchathani with an emphasis on local representation and grassroots engagement.

A Nam Yuen native, Wasawat has experienced the conflict not just as a politician, but as a local.

“Border people do not ask to be rich, nor do they want dreamy policies. What they want is simply a safe and stable life: the ability to live and eat well, fair agricultural crop prices, proper compensation and relief support and strong national security,” he told CNA while on the campaign trail.

“Because they live on the edge of the country, they don’t have a chance to speak up. I want to be a voice from the border,” he said.

For Vimol, sometimes forgetting about the situation feels easier. But she now has pets that remind her daily of the tensions with Thailand’s near neighbour.

Since December, she has had two new dogs in tow - a pair of rescues from a nearby school, found during the fighting.

She has named them Hun Sen and Hun Manet, after the Cambodian leaders she has watched endlessly on television in recent months.

“It’s very easy to remember their names and it reminds me not to forget about the war. We love the dogs so much,” she said, smiling broadly in a moment of levity amid her struggle.

“But the neighbours are always very surprised when I shout their names.”

DESPERATE ECONOMICS

For much of the nation, economic matters have been central to most parties’ campaigning during an election lead-up largely devoid of ideological contrasts.

The situation stretches far beyond those forced away from their land, stores and homes and into evacuation centres.

Across Isan, the poorest major region in Thailand with per capita output among the lowest nationwide, the situation feels desperate, locals told CNA.

The labour force is heavily reliant on agriculture. And household debt relative to local incomes is high, a key driver of economic stress and vulnerability among rural families.

Recent Bank of Thailand analysis showed sluggish economic activity and low business confidence in the region. Isan also suffers from structural issues like an ageing population and the out-migration of workers to other regions, where salaries are higher.

“The most urgent issue to address is the economy and cost of living, as this affects people nationwide. On other issues, opinions differ widely, making it harder to find common ground,” said Sathaporn Wichairam, an assistant professor in public administration at Buriram Rajabhat University.

In the very same market that Anutin toured briefly on his regional visit, vendors said they would support the prime minister; give him a chance to prove himself. But their pledges had economic caveats tied to them.

“If I have to choose, I’ll save my vote for Mr Anutin,” said Khemjira Poonsub, a vegetable seller.

“But I want them to see that our economy has worsened. This year is the worst, to the point that I don’t want to wake up to work anymore,” she said.

For sausage maker Burapa Phuengpha, the issue is debt.

“People have borrowed money in every possible way, but there’s no money left to repay it, to the point where they don’t even want to answer the phone anymore. It’s very widespread,” he said.

“These days, it’s really hard to survive. I want them to solve this the most.”

Bhumjaithai has packaged its economy-boosting policies and handout-style measures within a larger strategy it calls “Thailand Plus”.

Rather than sweeping stimulus, it has promoted small, direct cash supports tied to existing welfare schemes, a pragmatic form of populism aimed at easing daily pressure rather than promising structural change.

For Pitch, the political analyst from Chulalongkorn University, it is a “brilliant policy of giving people money” without attracting controversy or debate.

That contrasts with more expansive Pheu Thai policies of the recent past, such as its Digital Wallet, which promised 10,000 baht (US$318) per person to be spent within a limited time and geographic radius but raised concerns about fiscal sustainability.

After months of disruption and years of economic strain, voters in the northeast are being asked to choose between competing promises of security and support.

And how they respond will help shape the next government.

Additional reporting by Jarupat Karunyaprasit and Saksith Saiyasombut.