Typewriting the future: A dying art in a changing city

Typewriters still serve a critical role in the operations of government, banks and business in Myanmar. But it seems inevitable that soon they will disappear from Yangon’s streets.

Wai Wai Thaung is one of the younger masters of typewriting still in business in Yangon. (Photo: Jack Board)

YANGON: The tapping of keys is a familiar sound ringing through the old downtown streets of Yangon.

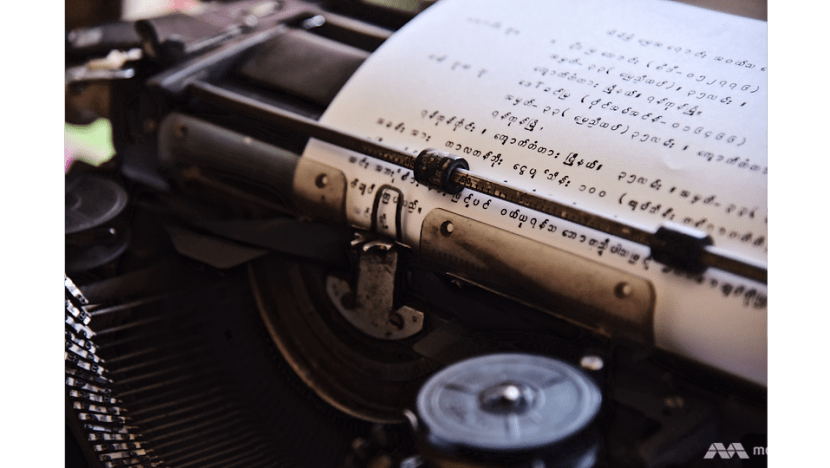

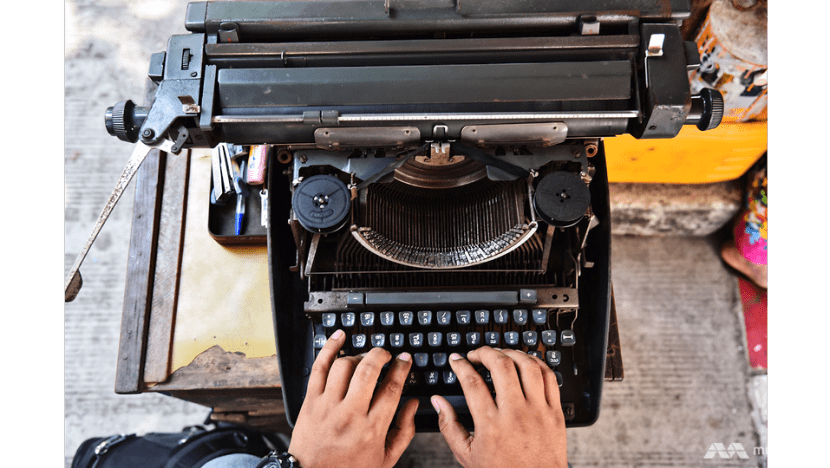

Mostly older typists sit on small enclaves in crumbling colonial buildings and on street corners under colourful umbrellas, their fingers a fury of precision. Using typewriters often older than themselves, they write up the likes of bonds, marriage certificates, and visa letters.

In Myanmar’s biggest city, it has been like this for decades.

While this type of technology was being phased out of operation in most parts of the world in the last millennium, the hardy typewriters and their dedicated operators remain a symbolic throwback to a bygone era.

After a prolonged stretch of military rule, Myanmar became a pariah state, which meant modern technology was almost completely inaccessible or prohibitively expensive. In lieu of the introduction of computers, typewriters used since colonial times were maintained.

Wai Wai Thaung is one of the younger masters of the craft on Bar Street in downtown Yangon. She describes how she first learned to type from her family.

“Since my childhood I am used to doing this work. My Dad and Aunty were doing it and I also had to help them. So I became skilful,” she said, while perched on a wooden stall in the business she now runs with her husband.

“It’s sure that the typewriters are going to disappear in the future. The computers will replace them,” she said.

“The computer is a modern machine. It’s easy to use and it’s appropriate for the modern age. To use the typewriter, you need to seriously learn its basic functions and it’s not so easy.

“Why I keep using the typewriter is just to preserve the legacy of my parents.”

It is a rare moment of sentimentality on these streets.

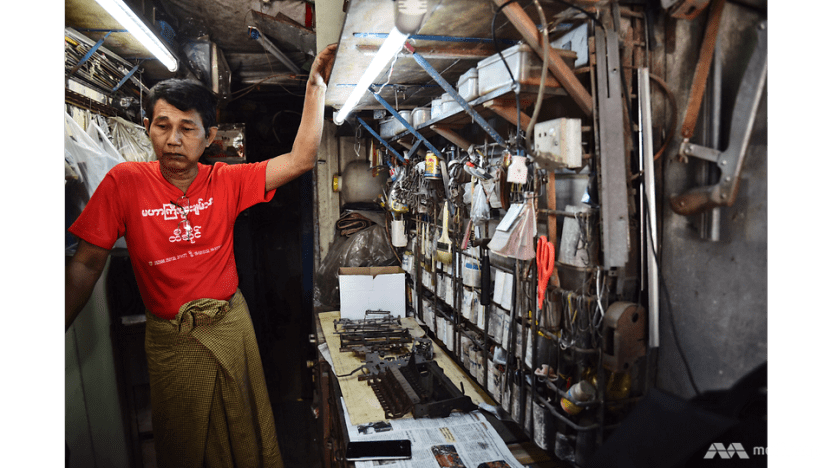

"I love it,” he says while demonstrating how to explore the inner workings of an old mimeograph machine, the precursor to photocopiers.

“The number of people who can fix typewriters is decreasing. Most of them are old and many of them have died,” he said. “But the business is decreasing.”

“This could be the last generation that has these techniques. The youth are just interested in computers.”

“At the moment I don’t have any time to think about the future. I just need to keep on doing this for my daily survival.”

“Lots of people don’t think about these things, or the value,” he said. He has lived in the same downtown home since 1968 and has watched generational change occur, transitions made more dramatic by the country’s turbulent politics over the decades.

Businesses have changed hands, neighbours have passed away or moved on and national leaders have risen and fallen. When the typewriter goes, while Yangon’s core may not carry the same mechanical whirring of the past, its purveyors will find new ways to move with the times.

“In Myanmar we don’t have a lot of sentimental value,” he said. “If it’s gone, it’s gone. Let it be.”