‘A sea of broken children’: COVID-19 leaves orphans, child labourers in its wake in India

Over 101,000 have lost their parents, while more families have fallen into dire straits – making children even more vulnerable to trafficking. They tell Insight about their pain and predicament.

Children who stopped studying during the pandemic may never go back to school.

BIHAR: When 10-year-old Shahbuddin’s* father died months ago, the weight of the world landed on his shoulders. The oldest of seven children, the burden of supporting the family fell to him.

The family had no land and no relatives to help with money. Shahbuddin’s mother was distraught and struggling. “My mom stays at home. She does not have money and she keeps on weeping. She begs for food and sometimes works as a daily wage worker in farms and feeds us,” he told CNA’s Insight programme.

An acquaintance from his village in India’s eastern Bihar state took advantage of his plight and lured him to leave home with the promise of a job.

This was how Shahbuddin found himself riding with 15 other children on a train towards Delhi, hundreds of kilometres away. They travelled 24 hours before arriving at the Anand Vihar station, where the acquaintance’s son left and Shahbuddin found himself alone and scared.

What saved Shahbuddin from ending up as child labour like scores of his peers – for now, at least – was a police raid on June 29 this year. Twelve traffickers were arrested for luring the children to work in a garment factory.

India made global headlines for its devastating second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in April and May. Many patients could not get hold of oxygen and crematoriums were overwhelmed. But another tragedy was also playing out.

Every child who is on the streets is a manifestation of failure of state.

Sonal Kapoor, founder of child rights group Protsahan India Foundation, calls it the “sea of broken children” – young ones who have lost their parents to the pandemic or have been forced to stop school, work as cheap labour or be married off as child brides.

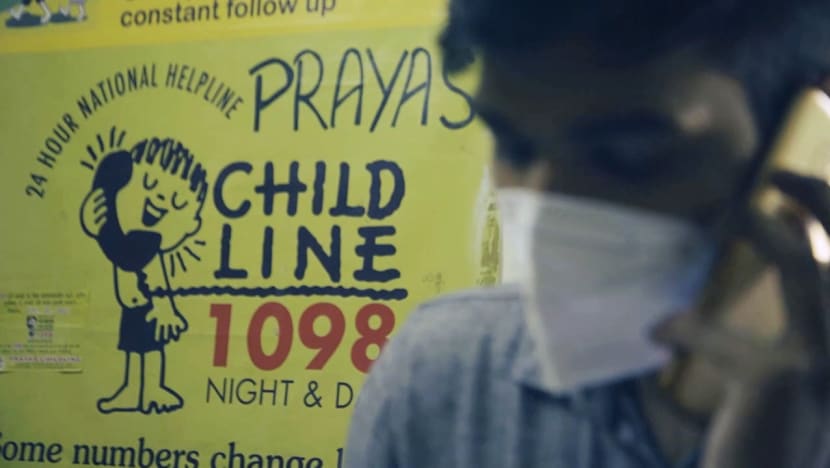

While these issues existed long before the pandemic, COVID-19 has aggravated the problems of children, said Amod Kanth, founder of the non-governmental organisation (NGO) Prayas.

TRAFFICKERS TARGET FAMILIES WITH ‘NO CHOICE’

In India, children below the age of 14 are not allowed to work in factories, mines or be engaged in hazardous employment.

Yet, the country’s 2011 census found that there were 10.1 million working children aged between five and 14. This figure was nearly 4 per cent of all children in the age group. In addition, the census found more than 42.7 million children to be out of school.

“Every child who is on the streets is a manifestation of failure of state. Every child who is out of school, every child who is begging, every child who has ever been a victim of any violence, sexual or otherwise, is an example of failure of state,” said Anurag Kundu, chairperson of the Delhi Commission For Protection of Child Rights .

Job losses and deaths caused by the pandemic have created fertile ground for child traffickers, as some families have “no choice but to push their children to labour, to begging”, he said.

“The traffickers are from around the villages and they know about the situation around there. They target vulnerable families,” said Rakesh Senger, executive director of programmes at the Kailash Satyarthi Children’s Foundation.

“In the supply chain, the trafficker is connected to the locals, who identify and tell them about the vulnerable families and the children who can be taken away.”

And where traffickers used to give about US$15 or 1,000 rupees as an advance to the children’s families, they now give US$150 to US$200 (11,255 to 15,000 rupees), Senger said. “So this way, the children become bonded labourers for a year."

Related:

Like Shahbuddin, 10-year-old Roshan* had to leave his home in Bihar to work in Delhi. His parents lost their livelihoods and borrowed from moneylenders. To repay the debts, Roshan worked in a bangle factory from 8am to 11pm for a monthly wage of US$30 to US$40.

His hands and legs ached from sitting and working in one position for long hours, and he was not given food on time. The chemicals used to make the bangles burned his face.

“I tried to run away once but could not because of the lockdown,” he said.

To make things worse, the boss shortchanged Roshan. “The owner told me that he sent US$40 but when I called my parents and asked about money, they said they received only US$27,” he said.

Roshan could get out only when Delhi-based Prayas raided the factory and rescued 45 children including him.

Vishal Kumar, Prayas’ child helpline coordinator, said rescuers saw children aged five to seven making bangles during their raid. “They were using harmful chemicals… and they would sit in the same position and work continuously for 10 to 12 hours,” he said.

SAVING LIVES THROUGH RAIDS

Raids require meticulous planning and can easily go awry, NGOs said. Traffickers also adjust the way they operate to evade law enforcers.

According to Vishal, if Prayas’ raid on the bangle factory had happened even five minutes later, it would have been difficult to save the children as news would have spread in the slum area.

Traffickers could make the children take longer bus routes and change buses to hoodwink enforcers, said Dhananjay Tingal, executive director of Bachpan Bachao Andolan (BBA), another NGO that conducts undercover investigations and raids.

But BBA has its networks to counter their tactics, he said. In certain districts, trafficking and child labour survivors take the lead and gather information on children being trafficked, which can lead to rescue operations.

Insight followed the team as it worked with district authorities to raid a garment factory using child labour in Seelampur in east Delhi. Earlier on, BBA had identified almost 30 children in four separate locations in the neighbourhood.

During the raid, the team had to move swiftly to avoid getting outsmarted as word of police presence spread and traffickers tried to move the children away in small batches. The children would also be taught to lie when they came face-to-face with the police – claiming that they were with their “uncles” or that they were merely sightseeing, for instance.

After 20 children were found, another obstacle surfaced: There was no sign of the traffickers or the children’s employer, and no one was divulging any information. The rescuers resorted to stern warnings – “you guys need a good slap, then you will straighten up” – and threats to seal up the premises to get a name from the workers.

In the end, it was a “good day” for the BBA team because the raid was successful. “You feel good that you have saved the life of a child,” said Tingal, who added that the children were aged 14 to 17 and two girls were among those rescued.

WATCH: How COVID-19 Created India's Broken Generation Of Children (48:23)

SECOND WAVE CLAIMS PARENTS

India’s Childline 1098, a 24-hour emergency number for children in need of help, received over 3.9 million calls about children between March and June 2020. It experienced a 50 per cent surge in calls in the three weeks from March 20 to April 10, 2020.

Figures for this year are not available. But according to Kundu, India’s first COVID-19 wave affected more people who were above age 50 — who were more likely to be grandparents — whereas in the second wave, it was “largely the parental generation who got affected, and that, in turn, adversely affected the children far more than the first wave”.

In one particular instance, there were two children inside a home with the dead bodies of their parents next to them and they were calling for cremation help.

The number of calls about children losing their parents was “heartbreaking”, said Kundu.

“In one particular instance, there were two children inside a home with the dead bodies of their parents next to them and they were calling for cremation help.”

According to the National Commission for Protection of Child Rights, over 101,000 children were orphaned or abandoned between April 1, 2020 and August 23 this year – children like siblings Shivam and Sakshi Gupta, who lost their father to the virus in April.

Estranged from their mother, who left when they were much younger, the pair now live with an uncle.

Related:

Sakshi, 15, and Shivam, 12, were very close to their father. When he was infected, he could not get admitted to the hospital initially, so they brought him warm water and medicine for fever and cough in bed.

He got worse four days later and was finally admitted to the hospital, but eventually died. “I miss him a lot,” said Sakshi. “I miss him teasing us, scolding us.”

“I used to be with my dad all the time. We’d go to the temple, or anywhere he had to go, I used to go along with him,” said Shivam.

Their uncle, Ravi, 41, told Insight he would look after the children even though he is a tailor who does not earn much – only about US$8 a day – and already has two children of his own.

“Whatever I am giving to my kids, they will receive the same,” he said. “It would be good if I get some help for their upbringing and education.”

In May, India’s prime minister Narendra Modi announced the PM-CARES for Children scheme which will support the education of children who have lost both parents or their surviving parent, or legal guardians to COVID-19.

But child rights activists say the focus on “COVID orphans” is problematic.

“It stigmatises one set of children who, for the rest of their lives, will now have to go around proving that they were orphaned by COVID-19 and therefore become eligible for certain benefits that the government has promised to them,” said Enakshi Ganguly, co-founder and advisor of the HAQ: Centre for Child Rights.

At the same time, it ignores the struggles of other vulnerable children, she added.

WATCH: India’s Stolen Generation, a 2016 Insight episode on child slavery and exploitation (50:08)

Two in three children in India have been subjected to physical and sexual abuse. Many have been raped and forced into prostitution. Insight travels to India to expose a harrowing story of child slavery and the fight to free millions from poverty and exploitation.

WITH NO SCHOOL, DREAMS SHATTER

The situation of girls like Pooja*, 13, shows that it isn’t easy to resume studies after a major disruption.

Some 1.5 million schools in India were closed from March last year due to the pandemic. Some children dropped out to work, and some dropped out because they could not access online education, said Ganguly. More than a year later, there are children who will perhaps never return to school, she said.

Pooja's father, the sole breadwinner, died without savings. Her family’s rent piled up to over US$300 and the teenager stopped school to help her mother and work for some extra income.

“If I continue my studies, then in the future I will be able to get a better salary, I could help others,” she said. “I want to continue my education, but it will take a lot to work and study at the same time.”

She added: “Now my dreams have been shattered. I have let them go, let them remain broken.”

There are little victories, however, such as of girls resisting early marriage in order to pursue their dreams.

Sisters Sapna, Suman and Monica Gujjar from Ajmer, Rajasthan, were due to be married off in May this year, but they vehemently refused.

Sapna, 16, said she wants to play football and is preparing for the civil service exams. The sisters’ resolve inspired their neighbour, Pinky Gujjar, to also refuse to become a child bride.

As for Shahbuddin, he was sent after the police raid to Mukti Ashram, a shelter for boys run by BBA. Although his family circumstances remain precarious, he has returned home and reunited with his siblings.

“I miss home,” he said. “I’ll come to Delhi for work only after I am 18 years old."

The successful rescues keep child rights activists fighting another day, but their work is always bittersweet.

“The biggest challenge is we are not able to reach out to all the children who are being trafficked and who are being exploited,” said BBA’s Tingal.

* denotes children whose full names have been withheld to protect their identities.

Editor's note: This story has been updated with the correct number of calls received by India’s Childline 1098 helpline between March and June last year.

Watch this episode of Insight: India’s Broken Generation here. The programme airs on Thursdays at 9pm.