These children have spent almost all their lives in public rental flats. What’s been the impact?

The programme Talking Point met three children and their families to find out how their living environment in public rental housing might affect their learning potential and mental health.

Vivian Tan (left), pictured here with her siblings, is one of the children living in public rental housing whom Talking Point met.

SINGAPORE: Every weekend, whilst she imagines other teenagers may be sleeping in or going out with their families, Wan Nur Wardina will be doing all the household chores in the morning.

Tidying up the house, sweeping and mopping the floor — the 17-year-old has been doing chores like these since she was young. “This (is) considered my responsibility … because my mum (works at) weekends,” she said.

They moved into their public rental flat when Wardina was eight years old, having previously lived in her grandfather’s rental flat since she was three.

Since she was 13, she has also been taking care of her brother, who is now five years old, while their mother is at work.

If she could choose to do anything other than tend to her chores and responsibilities, she would “go out and see (her) friends”, which she hardly gets to do at weekends. “I feel a lot (of) loneliness,” she said.

The teen, who is now at the Institute of Technical Education, sometimes also gets “stressed about finances”, for example when she has “no money to buy food”. She started working during the school holidays two years ago, delivering parcels.

She worries that she cannot go to school. “Or I worry (that) I can’t pay (for something) on that day,” she said, adding that all her responsibilities have affected her “a lot” at school.

Wardina is one of three children whom Talking Point met recently to find out what might be the impact of living in public rental flats on their learning potential and mental health.

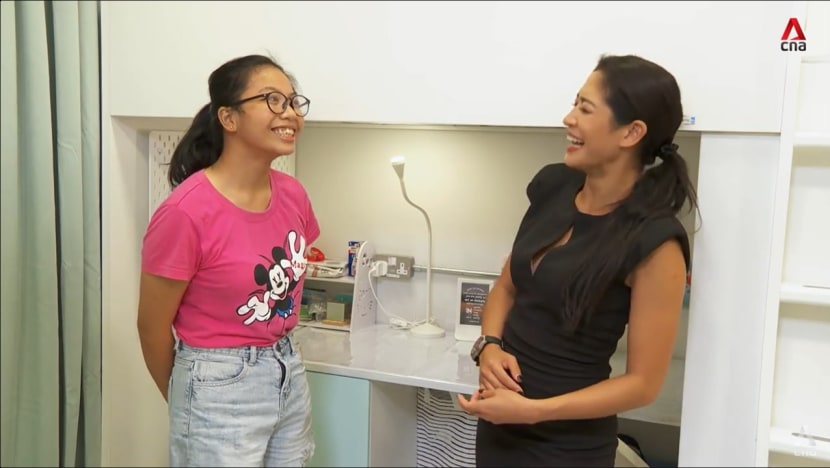

On the surface, they seem pretty together, coping with whatever resources they have, observed programme host Munah Bagharib. But they can hide their stress well.

THE SPACE ISSUE

There are currently 23,900 children aged 18 and below living in public rental housing. These flats are for Singaporeans who cannot afford to buy one and have no other housing options.

The rent payable is dependent on their household income, with monthly rents ranging from S$26 to S$205 for a one-room flat and S$44 to S$275 for a two-room flat.

Wong Hai Feng, 8, moved into his two-room flat when he was a year old. And he knows it is a rental flat because his parents told him.

“It means a flat that you rent from the government … for people who have low incomes,” he said. “It means you (don’t have) much money.”

When he gave Munah a tour of his flat, he remarked that there might not be enough space in the bedroom with his parents in future. “Because I’ll grow taller and taller. When I’m older, I’d like a big bedroom.”

A two-room rental flat, which usually comprises a bedroom, kitchen and living room, is about the size of three and a half car park lots. And the space constraints seemed to be something the children noticed, observed Munah.

For Vivian Tan, living in a 46-square-metre flat with four other family members means she does not have her friends come over. “It’s a small space, so they might be uncomfortable,” she said.

If her friends were to ask, the 13-year-old, who has lived in a rental flat since birth, would “say no because there’s nothing to do” or say that her parents do not allow it.

She cited her living room as “the most cramped area”, saying: “There’s a lot of things squeezed together, like the TV at the front, then the couch and then there’s a study table.”

At registered charity Care Community Services Society, where Catherine Foo heads the CareKids programme, about half of the children in low-income households she interacts with are from rental flats.

And she has seen some long-term outcomes of living in a cramped space. “Children can feel uncomfortable. They tend to develop loneliness (and) depression. (This can) sometimes affect their academics,” she said.

“Most often, children from rental homes … face greater stress (and) greater uncertainty.”

WATCH: Kids in rental flats — How does living in small spaces really affect children? (23:23)

Besides their concern about space, she said they experience “loss of control” as they think “nothing much that I can do can change the situation” — which can lead to “self-esteem issues”.

TESTING THE CHILDREN

No specific study has been done on the learning potential and emotional well-being of children who have spent their lives in public rental housing.

To get a sense of this, Talking Point sent Hai Feng, Vivian and Wardina for an assessment at Thomson Kids Specialised Learning. Besides being tested on their learning abilities, they filled in a questionnaire about their emotional well-being.

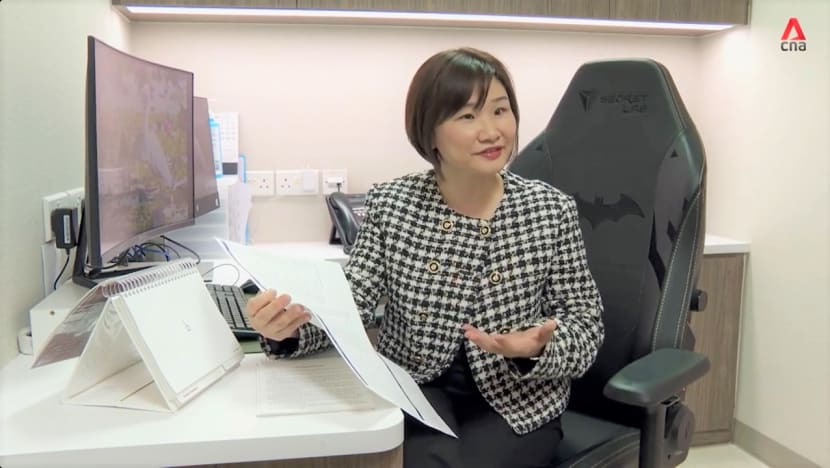

The questionnaire covered their feelings about school, their parents, their peers “and also how they perceive themselves”, cited Frances Yeo, the learning centre’s principal psychologist and programme director.

She said Hai Feng and Vivian did well in the academic achievement test and have also performed well in school, showing potential and even flourishing. Wardina, however, scored “much lower across all areas” compared with peers her age.

Wardina comes from a single-parent family, and they had struggled with family issues in her early childhood, observed Yeo. “She actually shows signs of dyslexia, so … there’s a very big literacy gap in her reading and writing level.”

In fact, all three children “showed indicators of behavioural issues, such as stress arising from academic performance”. Yeo said: “(They) also worried a lot about the future. They’ve struggled with … self-esteem. They worry about how others perceive them.”

By his own admission, homework stresses Hai Feng “because (he does) not get any help”. Yeo also expressed concern about him having difficulty paying attention and being “quite restless” — signs of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder — as well as his impulsivity.

“Another concern that he reported was not being able to get along with peers,” she said.

Vivian, too, worries about her academics and grades. And the results of her assessment show “a lot more anxiety and depressive symptoms” than peers her age.

Growing up in a public rental flat plays a part in some of these issues, according to Yeo. “(These students) usually don’t have a conducive study area for them to come home to and concentrate on their learning,” she said.

And when they can’t concentrate … that itself can cause stress, especially for Vivian. She wants to do well.”

In Wardina’s case, there is the added factor of looking after her brother.

“When children are assigned responsibilities at a very much younger age … that itself can be quite stressful for them, plus having to balance your schoolwork,” Yeo said. “It can cause, over time, accumulated stress … or depression.

“And when students come from rental flats, most of the parents aren’t aware of these conditions … and they aren’t likely to get help.”

GIVING THEM EQUAL OPPORTUNITY TO DREAM

The plight of rental flat children has not gone unnoticed, however. A new boarding facility for students from public rental flats has got off the ground. Accommodation is free, and it also has after-school programmes.

Run by charity =Dreams (Singapore), its campus in Haig Road took in 25 secondary school students for a start. Each of them got their own bed and study space as well as access to tuition, sport and arts activities.

One of the successful applicants was Vivian, who was “so excited and very happy” when she received her acceptance letter. She has been living there since January and goes home only at weekends.

She finds the rooms “very big”, and although she has weekly study-buddy sessions, she no longer must share her study space as she did with her two siblings. “(I’m) happy, because now things won’t get lost so easily,” she said.

One of the new things she is excited about learning is coding, and things are looking up. “(She has) a good opportunity here, and (it) can help guide her (to) where she wants to go,” said her mother, Santi Chong.

“Anything she asks me, I (don’t) really understand, like (when it comes to) education. And education, for me, is really important.”

It has taken =Dreams nearly two years to get the academic-focused facility going. Given the anxiety and self-esteem issues that students like Vivian may have, however, would the charity consider adding programmes to better help their mental well-being?

The short answer is yes, said chairman Stanley Tan. “But the long answer is that obviously the first thing we’ve got to be concerned about is their ability to cope with their schoolwork.

“Programmes aren’t cast in stone. We’ll modify them, evaluate them and include other aspects — so we do intend to be quite comprehensive in the way we explore what works best with these kids.”

He believes the facility is already different from other programmes in place for public rental households.

“There’s no (other) programme at the moment in terms of offering the children the full support of accommodation, academic help and life skill help,” he said.

“There are individual programmes that help them with studies, like tuition. There are programmes that help them with other activities but not consolidated in one place nor … done by the same, consistent group of people.”

WORRIED PARENTS

Many other rental flat children, however, do not have access to a structured programme like at =Dreams. And for the parents of Hai Feng and Wardina, parts of their children’s test results were worrying.

While Max Wong was “not surprised” that his son had a high hyperactivity score — because Hai Feng “keeps on jumping (around)” at home — he promised to look into the boy’s somewhat high anxiety score.

“I’m worried that he can’t talk to me or any of the schoolteachers. I’m scared that he might be reclusive,” said Wong. “I’ll try to rectify that.”

In the longer term, maybe in about five years’ time, Wong hopes to move to a three-room flat of their own. He is concerned that Hai Feng will not have his own room otherwise.

“It might affect his studies and all that,” said Wong. “When he grows up to a certain age, he’ll need space to develop.”

Wardina’s mother, meanwhile, was “shocked” by her daughter’s assessment scores, for example when it came to self-esteem.

“I couldn’t believe that she has those weaknesses … and her stress, (which) she never (shared) with me,” said Nur Sakinah Lai, who was “quite worried” about Wardina’s mental health.

“I don’t really know what she’s thinking about … because most of the time, she knows that I’m very tired (from) working … 12 hours in a day.”

But if Lai can do something about it, she would. “Maybe I’ll just spend more time with her and (make) her a little (less) stressed,” she said.

When it comes to living in a rental flat, however, Wardina herself does not make an issue of it. After living in one for most of her life, she envisages continuing to do so in in the long term.

“We’re grateful that we’re staying (in) a rental flat. At least we have a house,” she said.

Watch this episode of Talking Point here. The programme airs on Channel 5 every Thursday at 9.30pm.