Need a daily caffeine fix? Here’s why your cup of coffee is getting more expensive

Coffee producers are facing many challenges now, and the programme Talking Point heads to Indonesia, the source of Singapore’s traditional ‘kopi’, to find out what these are, what can be done and whether prices will continue to rise.

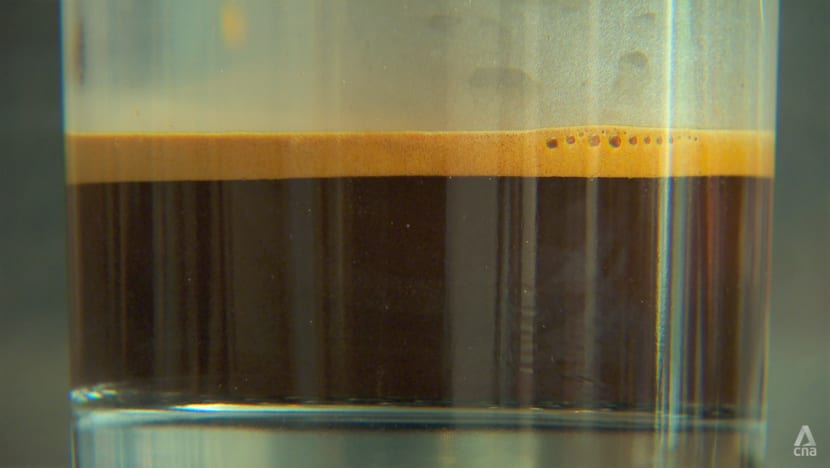

Many things may affect the price of a cup of coffee.

SINGAPORE: It does not seem much: a 0.6 per cent fall in Indonesia’s coffee production this year, according to estimates released last December by the country’s Ministry of Agriculture.

But it is the first such fall since 2019. And as supplies of Indonesian robusta coffee — the kind that is largely found in Singapore’s hawker centres and coffee shops — come down, prices are shooting up.

“In the last four, five months, we’ve seen the robusta prices in Indonesia move very drastically. It’s now around S$240 for a 60-kilogramme bag,” said Singapore Coffee Association president Victor Mah. About a year ago, traders were paying S$180.

Singapore’s consumer price index shows that the average price of a cup of “kopi” (traditional coffee with milk) was S$1.35 in August, which is 7 per cent more than last year’s average price of S$1.26.

And it could yet get more expensive. The United States Department of Agriculture forecast in June that Indonesia’s 2023/24 coffee output will fall 18 per cent from a year ago to its lowest level since 2011/12.

In a two-part special, the programme Talking Point explores the factors behind the drop and what else is driving the price rises.

FROM CLIMATIC CONDITIONS TO PESTS

More than 90 per cent of coffee plantations in Indonesia are smallholdings, such as the one owned by second-generation coffee farmer Kerno in Lampung, Sumatra’s southernmost province and one of the country’s biggest robusta-producing regions.

The 50-year-old, who goes by one name, has around 5,000 trees on his farm about the size of two and a half football fields.

Last year, he harvested three tonnes of coffee cherries, the fruit produced by coffee trees inside of which are the coffee beans. This year, he hopes his harvest will be around one tonne.

“It may not even reach that amount. We’d be lucky if we get 800kg,” he said.

Sumatra has been subject to frequent rain and occasional freak weather since last year, which has disturbed coffee trees at a crucial period of the production process.

“After the flowering stage, the flowers turn into small cherries. (But) the heavy rain causes them to fall off. They’ll rot and won’t turn into coffee. Therefore, it isn’t possible to get a big harvest,” said Kerno.

“We lose out to the weather. It’s very sad.”

Other areas in Indonesia have even been hit by hailstorms, which have also affected coffee production.

WATCH: Part 1 — Why is my coffee getting so expensive? (22:28)

It is not only the weather that can be volatile, but also fertiliser prices, which hit a peak last year because the pandemic, the Russian invasion of Ukraine and other supply chain issues tightened global supply.

Prices remain at historically elevated levels: 50kg of fertiliser that cost Kerno around 200,000 rupiah (S$18) in the past is now priced at 260,000 rupiah.

“When we farmers are hit with the skyrocketing cost of fertiliser, we won’t use as much,” he said. “That leads to lower coffee production too.”

The threats to coffee supplies are not confined to Indonesia.

Temperature increases around the world have led to the proliferation of a pest called the coffee berry borer. These borers are not only becoming more fertile, but also drilling deeper into the coffee cherries.

As they eat their way in, the fruit’s weight reduces. Severely infected cherries drop from the trees, which means they do not ripen and cannot be sold.

Climate change — and its impact on weather conditions — is also causing a rise in diseases such as coffee leaf rust, a fungal disease that reduces coffee yield.

Globally, coffee production decreased by 1.4 per cent in 2021/22. Although a rebound is projected this year, consumption is also set to increase. For the second year running, coffee producers cannot keep up.

In August, the International Coffee Organisation estimated a shortfall of 7.3 million bags this year.

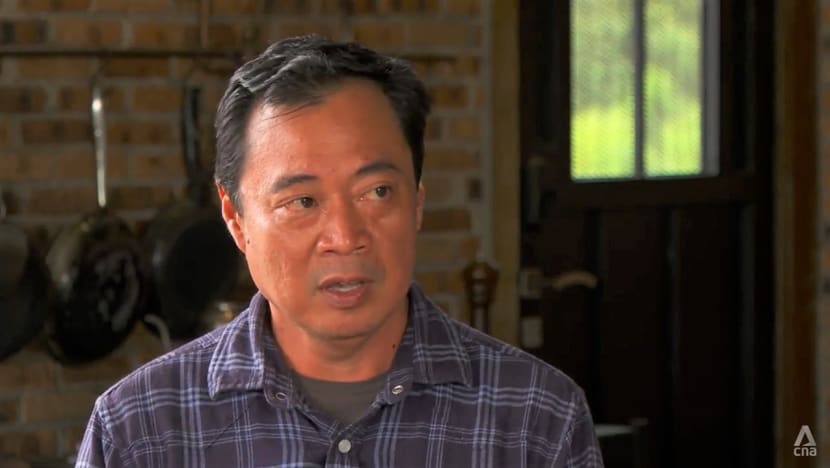

More coffee is being consumed in Indonesia too. “Every year, the rate of consumption is getting higher and higher,” said Leo Wiriadjaja, co-founder of Lisa and Leo’s Organic Coffee, a farm in North Sumatra.

“That takes away the amount of coffee we can export.”

Then there is El Niño this year. With its hot and dry weather conditions likely to be prolonged, industry players expect a further strain on coffee production and a shortage in supply going into next year.

THERE ARE SOLUTIONS

Despite the challenges faced by Indonesia’s coffee farmers, Wiriadjaja’s plantation — which he owns with his wife, Lisa Matthews — is thriving.

One of the reasons they have kept their coffee yields consistent is they use organic fertiliser, that is material they have composted, such as cut grass and by-products of coffee production.

The coffee cherry and the skin of coffee beans, for example, have macronutrient and mineral content for the crops, such as potassium, copper and zinc. The cut grass contains nutrients including carbon, nitrogen and phosphorus.

“By having all of the elements in the compost provided by us from our farm, we know what’s in it. And we can control the microbiology in it,” said Matthews.

“When you buy synthetic fertiliser, you’re relying on what’s printed on the outside of the bag to be what’s on the inside.

“But a lot of farmers have found out that sometimes the fillers (added to) these fertiliser bags can be detrimental to the crop. They can introduce the wrong kind of bacteria.”

The use of compost, rather than synthetic fertiliser, also results in an annual cost saving of 30 per cent for the farm, reckoned the soil expert.

The couple have another natural type of fertiliser growing all over their farm - yellow clover.

“It creates a healthy biology within the soil by producing nodules on the end. That contains the nitrogen. And that’s released into the microbes. The microbes change it into an absorbable form for the trees, and it keeps the leaves healthy,” said Matthews.

Masses of clover also prevent high temperatures from baking the topsoil. They grow “just on top of the ground”, which creates shade and prevents the soil from “drying out”.

“The roots that they have absorb lots of moisture. And then they release it later into the soil,” she added.

Besides the clover on her farm, there are shade trees towering over the coffee trees. Their function is to lower the temperature, break up the wind and, through their root system, feed the soil with the nitrogen that coffee needs.

“Because the temperature’s lowered, … (the coffee trees) have less stress. They can put their energy into developing the flowers,” said Matthews. The cherries that grow will be heavier — thus yielding more coffee — than those grown by trees in full sun.

She also grows flowering plants (lantanas for instance) to attract pollinators such as bees to her farm. These insects will carry pollen that fertilises the coffee flowers.

“Severe rains will affect the natural pollination of the coffee tree. Not all of those flowers will become a coffee cherry if they’re not properly pollinated,” she said.

The lantana she plants has another useful function: It attracts what is called a predator wasp, which eats coffee berry borers.

To further reduce losses from borer infestation, there is a method that can be employed when processing the cherries to get the coffee beans: Instead of using jute bags or gunnysacks, farmers can use drums for “controlled fermentation”, cited Wiriadjaja.

“This is better because you can reduce the available oxygen,” he said. “The lack of oxygen … will suffocate (any borers in the cherries).”

Instead of losing up to 30 per cent of their harvests to the pests, farmers could reduce their losses to under 4 per cent, he added.

His farm produces arabica, which is considered a superior quality coffee and is commonly served in Singapore’s cafes and restaurants. A 60kg bag of arabica beans averages about thrice the import price of the Indonesian robusta.

Around 27 per cent of the coffee produced by Indonesia’s smallholders is of the arabica variety. But Wiriadjaja and Matthews run free workshops teaching their farming methods, hoping these can inspire other coffee farmers.

WATCH: Part 2 — Will this new breed of coffee plant mean cheaper coffee? (23:25)

Other experts and non-governmental organisations, too, have helped farmers improve their agricultural techniques over the years.

"MANY LITTLE THINGS" ADDING UP

The rise in the price of Singapore’s “kopi” does not all come down to coffee bean prices, however.

Last year, Ya Kun Kaya Toast, which has more than 70 outlets in Singapore, increased the price of its coffee with condensed milk from S$1.80 to S$2.

Contributing to that were “many little things coming together”, such as rental, labour costs, medical benefits for the staff and electricity bills.

“These things will also continue to creep (up),” said Ya Kun International’s director of branding and market development, Jesher Loi. “You’ve got to deconstruct the various ingredients involved as well: coffee beans, water, milk, sugar.

“The profit margin (on) each little cup of coffee has to be put together … to prop the business up.”

Overall manpower costs in post-pandemic Singapore have “increased significantly”, agreed Kang Yi Yang, the sales director of Santino, a supplier of roasted coffee beans to local coffee shops.

The roasting process, which is what turns the green coffee beans that arrive in Singapore into dark brown beans, presents a challenge too. “It uses a lot of electricity and also gas,” said Kang.

Last year, our utility costs doubled. … It’s very volatile right now.”

And the cost of some of the raw ingredients that go through the roasting process has increased. Sugar costs about 55 per cent more than in 2021, while margarine costs 20 per cent more.

“Sugar gives (coffee) more caramelised flavours. It gives (coffee) its body and sweetness. As for the margarine, it makes the whole coffee more aromatic, … the roasting process a lot smoother,” said Kang.

“We have no choice (but) to add in all these ingredients to … maintain the flavours of … our traditional coffee.”

Very likely it all points to a more expensive cup of coffee going forward, he concluded.

Watch Talking Point’s two-part special here and here. The programme airs on Channel 5 every Thursday at 9.30pm.