Praised for going from gang to ITE to NUS, this graduate doesn’t want to be stuck with a label

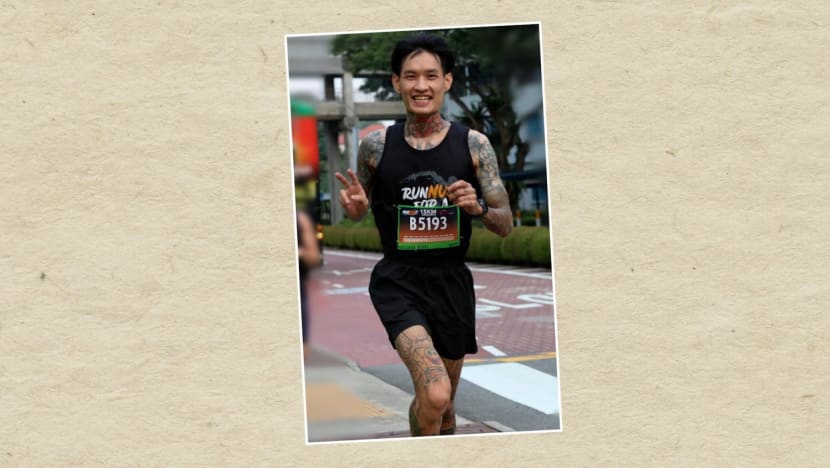

Twice sent to juvenile detention, Gary Lau went on to graduate with the highest distinction in social work. But he questions the characterisation of him as a poster child for how to succeed academically despite a troubled background. The 31-year-old opens up to CNA Insider.

Gary Lau, 31, is now a social worker. (Photo: Eileen Chew/CNA)

SINGAPORE: There have been some scary moments in Gary Lau’s life: When he was a child and his mother’s boyfriend would abuse her; during his time in a gang as a teen; and at university in his late 20s.

Of these, his four years at the National University of Singapore (NUS) may seem the outlier, free of the violence of the past and culminating in his graduation this year, at age 31, with the highest distinction in social work.

But that belies what the former Institute of Technical Education (ITE) student overcame to get through university, to become the social worker he is today.

“It was quite scary to be in an environment where — I wouldn’t say all, but most — people seem to be able to speak very well,” he said.

“In ITE and poly, even (among) my past gang mates, we just spoke chapalang, broken English … But when I entered uni, I was always reminded, subconsciously or consciously, that I had to speak well so that I won’t feel embarrassed.”

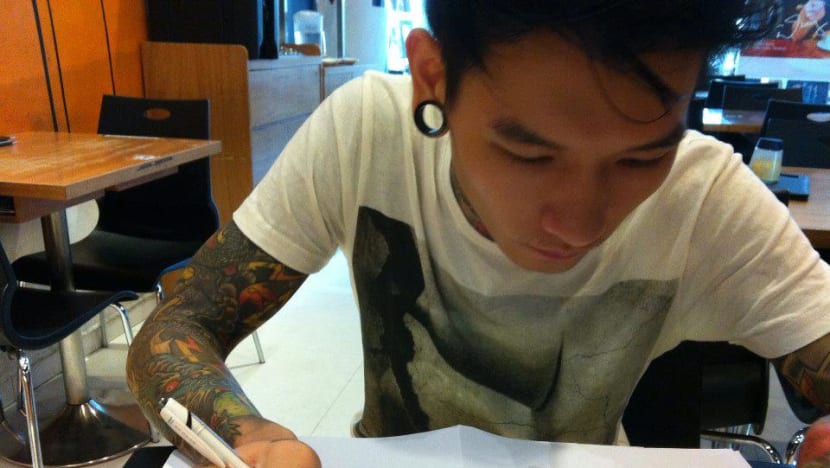

If it was not his language that he was minding, it was the reactions to his appearance.

“I’d have negative thoughts. Like what would my peers, lecturers and even the uncles and aunties in the food stalls think about me because of my tattoos?” he recalled. “Would I be seen as if I’m a cleaner or something?

“People tend to have this stereotypical mindset when they see tattoos. It’s either you’re from a gang, (or) you’re a tattoo artist — I got that a lot.”

Some of his classmates were initially afraid of him, he said, although he realised it only after friendships were formed and they mentioned it to him.

Then there were peers who would walk past him without batting an eyelid at his tattoos, he remembered. That made him feel happy, as though he was “one of them”.

As far as he knew, however, his background was different from almost everyone else’s. He was sent twice to the Singapore Boys’ Home, a juvenile detention centre, before he “started to behave better”, in his words.

His troubled past was cited by NUS in a Facebook post highlighting his latest achievement. The post went viral, and he has received many messages of congratulations.

But this has left him with “mixed feelings”. The characterisation of him as a poster child for how to succeed academically despite a troubled background, to him, is a label, and one that he questions.

WATCH: I'm not a label: From gang to ITE to NUS graduate, now social worker (11:05)

He sat down with CNA Insider to provide an unvarnished glimpse of Gary Lau the person.

THINKING POSITIVELY, AT FIRST

On his first day at university, Lau naturally felt excited. “Because getting into NUS wasn’t easy, right, especially coming from my background,” he said.

At the same time, he went into university “without any expectations”, with an open mind and with the thinking that “I’ve already got into NUS, and I believe that I’m kind of capable of studying”.

But that positivity turned into “slightly more negative” thoughts as he got to know his new environment and how unfamiliar it was.

It did not help that he felt the chemistry was not there between him and other undergraduates. Until today, he cannot quite put his finger on it.

“Probably age? Probably background. I think these two may be the big factors, and also my personality,” said the self-described introvert.

“I just wanted to stick with a few close friends, but at the same time I couldn’t find the friends that I could connect (with).”

Although he tried to fit in — even as he stayed true to himself, he stressed — he did not feel the sense of belonging he felt when he was a gang member.

‘I VALUED TOUGHNESS’

He was 14 years old when he joined a gang. He did it “without a second thought” when an older student at his secondary school, who had treated Lau “like his brother”, asked him if he wanted to.

“I think I valued toughness when I was younger,” he said thoughtfully. “I think that was one of the many factors that led me to the gang.”

Joining the gang then led to “underage clubbing, drinking, underage sex”. Smoking was common, though he had already started the habit while he was in primary school.

“If one of our brothers (felt) down, we would, (even at) 2am, 3am, go … and listen to them or help them,” he said. “We knew how to have fun, and also tried to support one another.”

They also fought others. In one incident he cited, he was beaten up by more than 10 people from a rival gang and “almost lost (his) life”.

On another occasion, he led a group to beat up someone, and the person went partially blind. “That was the first time I actually felt guilty, and we got caught by the police,” Lau recounted.

“I think I was very irresponsible as a teenager.”

The thing he regrets the most was making his then girlfriend pregnant. She went for an abortion because they were too young, he said softly.

LIVING IN A SINGLE-PARENT HOME

Lau was soft-spoken throughout much of his conversation with CNA Insider — perhaps not quite the manner of a rebel child, but rather of someone who, as he said, “didn’t express any emotions” or share his problems when he was younger.

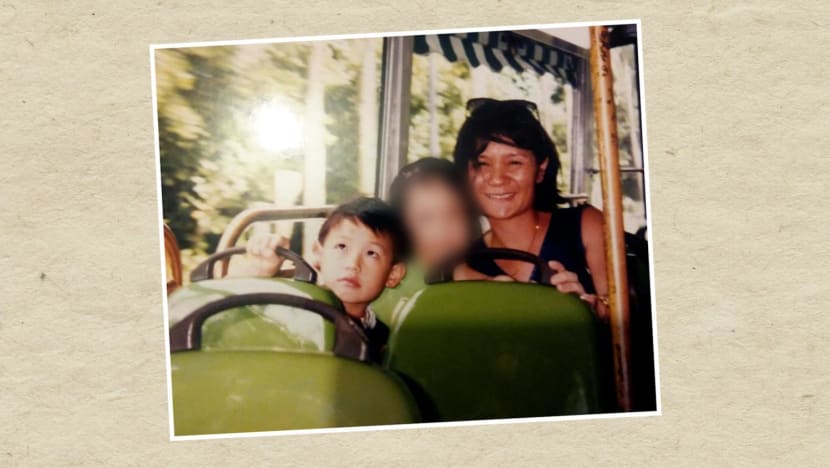

He was three years old when his parents divorced. He was in the care of his mother, who he remembered was “always busy” working two jobs: As a restaurant cashier and a KTV waitress.

When he was in Primary Four, his mother had a boyfriend who was abusive towards her, physically and emotionally.

“I’d lock myself in the room, sit in the corner and cry. I felt quite helpless in the sense that (I asked myself) why this quarrelling and fighting always happened but no one came to rescue us,” he recalled.

His mother ditched her boyfriend after two years. By then, Lau “was quite rebellious”, he acknowledged.

He could later perceive that she was worried about him being in a gang. Things came to a head when he brought his gang mates home and she kicked them out.

“My mindset was: If you don’t respect my friends, you don’t respect me. And because of that, I ran away from home,” he recounted.

Today, he is at pains to acknowledge that she “did try her best … to provide the care that a son needs”.

STARTING ANEW IN BOYS’ TOWN

Lau’s mother needed help, however, so she applied for a Beyond Parental Control order, now known as a Family Guidance Order. Two weeks after he ran away from home, the police nabbed him.

He was sent to the Singapore Boys’ Home before being transferred to Boys’ Town, a charity running a residential care home, where he stayed for a year.

But after he was caught glue-sniffing, he was remanded to the Singapore Boys’ Home again. Whether he would remain there this time or return to residential care hinged on an interview he would have with the Boys’ Town assistant director.

“I said, ‘Please ah, please ah, take me back,’” recalled Lau, who feared a lengthy placement in the Boys’ Home.

“That was my first time sharing a bit of my personal story also. That kind of touched him a bit. (I could) see a bit of a tear in his eye.”

Lau returned to Boys’ Town and started anew. The assistant director also monitored him closely and sometimes invited him to help with some office paperwork, rewarding him with snacks and toiletries.

“It was like (having) a father figure that I didn’t …” Lau said, pausing to find the right words, before continuing, “… that connection I didn’t feel before.”

A STRING OF REJECTIONS, THEN A CHANCE

In his time at Boys’ Town, he got to serve a work attachment with youth-oriented restaurant Eighteen Chefs. It motivated him to apply to a culinary institution after his National Service. But he was rejected.

“The course manager (said) my tattoos were too obvious, so it was quite difficult to take me (on),” Lau recalled.

I wasn’t angry at all, but I was of course upset. And I started questioning … why society is treating people like us like this.”

He remembers turning to his relatives for financial support so he could take a diploma in a private school. Summing up their response, he said: “No one helped me lor.”

He was at a loss what to do until he sought out his former social worker, Gwen Koh. He was doing volunteer work at the time, and she realised he could connect well with the at-risk youth he was helping.

She pointed him towards social work, and he applied for ITE’s community care and social services course. But he was initially rejected because of his poor N level results.

Koh helped to plead his case. And the deputy director of health sciences at ITE College East, Tay Wei Sern, gave him a chance to sit the entrance test, which Lau passed.

At age 23, he enrolled at the ITE. He started off driven to do well and to “prove others wrong”. His expectations “weren’t that high”, however, so he surprised himself by achieving a perfect grade-point average in his first semester.

“I realised that, actually, I can study,” he said.

Throughout the course, he maintained his perfect score, which got him into Nanyang Polytechnic. And in his final year at polytechnic, he had a thought that never occurred to him before: “I’ve been doing so (well), why not just continue (at) NUS?”

When he started out in the ITE, what he wanted was “to pass and move on”, he said. “I didn’t think … my end goal was to be in NUS.

“I didn’t think I could get into NUS, but finally I got into NUS.”

REFLECTIONS

Looking back on all the obstacles he has faced, Lau allowed himself a wry smile. “I think I was very positive,” he said. “When I fall, I just pick myself up and keep on going forward.”

Perseverance matters, he added contemplatively as he folded his arms and gave more thought to what he has learnt. “But I think the most important one is social acceptance: You need people to support you, to advocate for you.

I don’t know where I’d be … if I didn’t take the effort to call my former social worker after four to five years. So I think social connections are important.”

He has also thought about the different treatment he now gets, and what it says about the idea of success in Singapore.

“When I was no one in the sense that I didn’t have qualifications at all … I was still treated normally by my group of friends from the same background,” he said.

“When I slowly got good grades, awards (and) certificates, then more people from all walks of life started to come to me … (and) say things like, ‘Wow, congrats.’”

He admitted to feeling a bit conflicted. “I’m not going to lie lah. When people praise me, I feel happy on the inside,” he said. “It can be quite sad also lah, because it seems like people are quite materialistic.”

And it seems to him that he is “being labelled” when people laud him for having “come so far” despite his background. “(In) my ITE days … people appreciated me as a person, and I find that more genuine,” he said.

GIVING BACK

For the record, he does not think he is successful yet. “Not now as a fresh graduate. In the future, I can contribute a lot to the social work sector,” he said.

He hopes, for example, to integrate technology into social work. In his free time, he has been learning coding and user interface/user experience design so he can build apps that could help social workers and their clients in different settings.

Lau is starting full-time work this month as a community social worker, a member of a team engaging with residents in rental flats, especially children and youth.

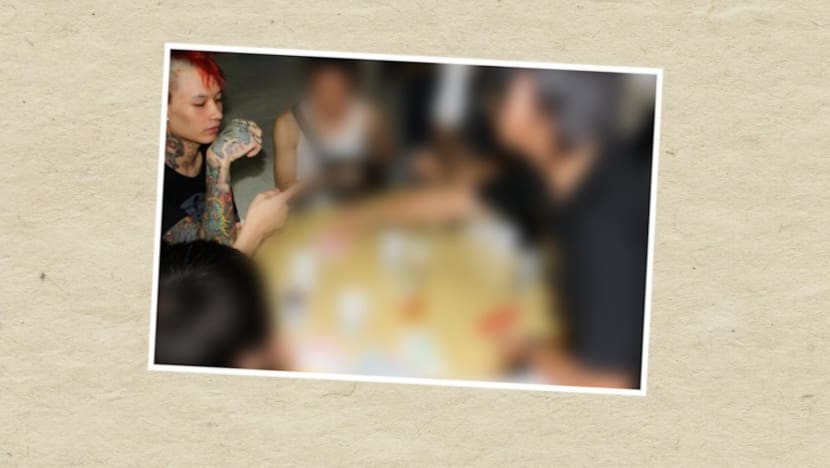

He is no greenhorn, however. In his polytechnic days, he started a free tuition initiative, called Happy Children Happy Future, for lower-income youngsters.

It reached out to families in rental flats and eventually partnered Residents’ Committees (RC) as the tuition shifted from homes to RC centres — as many as eight centres at one stage.

Lau has also inspired youths who have read or flipped through his self-published book titled I Am Not A Label, I Am Gary. It traces his various life journeys, from his early days to his admission to NUS.

One of the things from experience that he would like to remind at-risk youth is “they’re not alone”.

And if there is anything his life has taught him, it is that anything is possible “with the right mindset and effort (and) the right social resources”.

“Because look at me — I have so many tattoos, my N levels were so cui, so poor, so jialat. I’m still able to be where I am today,” he said.

“Youths would come to me and say that they want to be like me one day … I always hope that one day they’ll be better than me … And I believe that they can. But I always tell them, most importantly, you must tell yourself that you can.”

_1.jpg?itok=Pt4lopXb)