‘I regret committing crime’: Inside the Probation Service and lives of youth offenders

When the courts decide to keep young offenders out of jail, it is up to one team to find out how they can be rehabilitated. CNA gets an unprecedented look at the work of Singapore’s probation officers.

At least eight in 10 probationers are under the age of 21. Some of them are electronically tagged.

Note: The names of the offenders have been changed.

SINGAPORE: Previously, Lee was so “sexually preoccupied” that he “couldn’t concentrate” on his studies.

“When I was in my room alone, I’d have the temptation to watch pornography,” said the 19-year-old.

It came to the point where he tried to “seek a higher level of sexual gratification”. That was when, at the age of 18, he committed voyeurism.

“I knew that was wrong, but it was very hard to shut out the unhealthy thoughts, which flooded my mind,” he said.

He was given 21 months’ probation and assigned an officer from the Ministry of Social and Family Development’s (MSF’s) Probation and Community Rehabilitation Service.

WATCH: Can an 18-year-old Peeping Tom be rehabilitated? A probationer’s tale (4:37)

Nine months into the probation and the officer, Yeo Kheng Hao, was still checking the browser history and chats on Lee’s phone.

The youth’s mother was doing the same on all his devices every morning and telling him not to watch anything porn-related.

“There’s no condition to say that he can’t watch porn. But it’s part of our intervention plan,” said Yeo.

“For those cases (who can’t abstain), you’d want to find out what’s the frequency, how intense. For many of them, it could be a trigger (for) reoffending behaviours.”

There is still some way to go in Lee’s rehabilitation journey, and it is not necessarily going to be a smooth one.

But when the courts decide to keep offenders out of jail, it is up to the Probation Service — with the youths’ families — to find out how they can be rehabilitated.

It requires an understanding of what leads teens astray and is now featured in the series Inside The Probation Service.

For the first time, CNA followed a team of probation officers whose job is to stop young offenders from heading into a life of crime.

‘AN OPPORTUNITY TO INTERVENE’

Probation is essentially supervision of an offender in the community, which means the person is able to go to school or work. Probationers or those who have completed their probation orders can lawfully declare that they have no criminal record.

“It’s a second chance because it’s an opportunity for them to recognise the harm that they’ve caused others, to make amends, to stop offending,” said chief probation officer Carmelia Nathen, the director of the Probation Service.

“If not for probation, the court can commit them to an institution like a juvenile rehab centre, or to prison.”

In 2019, her agency investigated 671 cases to evaluate their suitability for probation. They committed a wide range of crimes, from cheating and criminal trespass to unlawful assembly and voluntarily causing hurt, or even driving offences.

One that is a “very sensitive” issue is sexual offending. “There’s a lot of embarrassment, and a tendency also for families and youths to downplay the seriousness,” said Nathen.

“But it shouldn’t be minimised or trivialised. In the longer run, we don’t want such behaviours to get more entrenched or to escalate. And so if there’s an opportunity to intervene early, to address the issues, then we should.”

In the case of Lee, his regular sessions with Yeo include the officer probing into his feelings, say, in response to sexual stimulus in advertisements or movies.

“Asking these questions … is just part and parcel of the job,” said Yeo. “I’d be looking at the offence itself, being very objective.”

Offenders like Lee must write down their thoughts on a daily basis, as well as the frequency of masturbation, said senior principal forensic psychologist Jennifer Teoh, the director of the MSF’s clinical and forensic psychology service.

“Such external monitoring is important because eventually we want to build up their internal control,” she said.

For his part, Lee must make an effort to not think about sex. “I’d stop whatever I’m doing, and I’d take a deep breath and then try to clear my mind,” he said.

He also deleted TikTok and Instagram, as there may be nudity or “females exposed”.

Among sexual offenders, “a common risk factor is early exposure (to) internet pornography”, which could “lead to a deviant sexual arousal pattern”, said Teoh. “That means they no longer get aroused by normal stimulus.”

Most sex offenders “don’t have mental illness”, she noted. “It’s about them having distorted thinking about sexuality. For example, they might think that a girl who wears a short skirt may be okay to have sex (with).

“Such distorted thinking will need to be corrected in interventions because it can lead to deviant sexual interests.”

Nowadays whenever Lee has a sexual urge, he tells himself: “You need to suppress it. No matter what, you can’t reoffend.”

What has “progressively” helped him increase his self-control has been his workouts in the gym. “Miraculously, the sexual urge doesn’t come up as often,” he said.

When he was caught being a Peeping Tom, he felt “very bad” and “a sense of guilt”. He was also worried about how his family would feel and about losing friends. “They were very angry and also shocked,” he recalled.

He was afraid that the public would recognise him and have a low opinion of him. “But slowly, I started to overcome that fear by stepping out of the house,” he said, crediting those around him.

“My family would go out for some religious events and shopping, for me not to feel bored, which might lead me to reoffend.

“Whenever I’m feeling down or bad, I have my mum, as she’s at home every day. And I’m thankful that most of my friends have supported me throughout my probation.”

THE INVESTIGATION

So how does the Probation Service evaluate these minors’ suitability for community-based rehabilitation in the first place?

For one thing, the officers must ensure that public safety is guarded, which is why it takes about four to six weeks to assess a case.

“The probation officer considers many factors in assessing whether they’re suitable for probation or not: Whether they’re involved in school or any positive activities, whether they’re motivated to change,” cited assistant director (operations management and strategy) Gabriel Low.

“We also look at the severity of the offence, their history of offending behaviour as well as the family make-up.”

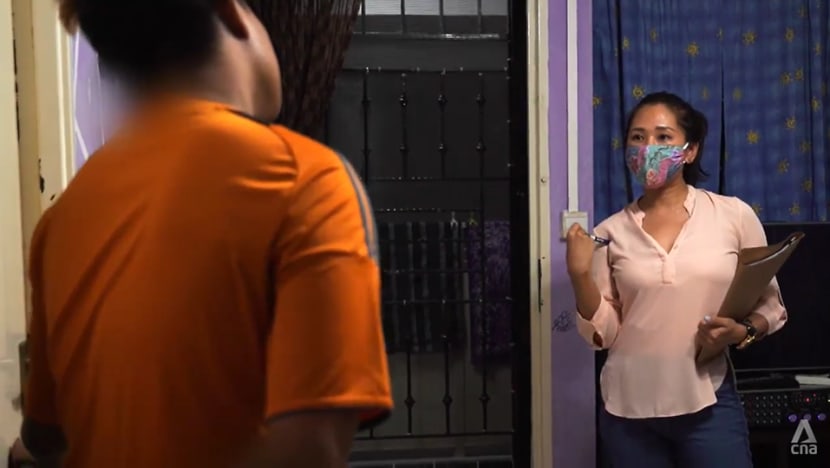

Sometimes the investigation throws up inconsistencies in statements, as it did when Charis Chenxu was evaluating the case of 16-year-old Ahmad, who was charged with rioting, receiving stolen property and violating circuit-breaker rules.

In the first interview, his parents reported that he would stay out all night “probably just once a month to fish”. In the second session, he himself said he was not allowed to stay out late.

But when Chenxu highlighted that he may have to follow time restrictions — sometimes given to offenders during investigations to see if they can comply with instructions — she learned that he was “not used to getting home early”, in his words.

In fact, he was used to staying out three or four times a week. His father, however, said he was “not sure” about this.

“Even if the details aren’t offence-related at all, we still want them to be forthcoming because these can give us insight into the youth’s offending behaviour,” said Chenxu. “If they’re not truthful, it could affect our assessment.”

At least eight in 10 probationers are under the age of 21, and family support is a factor in considering youth offenders for probation.

Youths who have experienced “relatively poor” parental supervision “get charged at a much earlier age”, said senior principal clinical and forensic psychologist Chu Chi Meng, the director of the National Council of Social Service’s Translational Social Research Division.

“And what happens is, when they come into the system, they tend to also re-offend fast.”

This makes home visits "crucial" to probation officers’ investigations, said Chenxu. “Because we’re able to pick up any concerns.”

For Ahmad’s family of eight, home is a two-room flat. On one of the days, recounted Chenxu, his father told her he “might even consider” a divorce, which she presumed was said “in a fit of anger”.

“This could possibly be something that’s been happening for quite a while already: The inconsistency in parenting and supervision,” she said.

Ahmad’s suitability to serve probation at home was open to question also because he did not follow her instructions. “If he wanted to work, he had to ask me for approval first,” she cited.

“Despite this instruction, he went to (find) work without informing me. He was frustrated, and then he responded in a way that was quite rude. After that, whatever messages I sent or any calls I made, he didn’t pick up.”

There is a reason youths like him would have to get permission before applying for a job: “To make sure that the jobs that the youth has applied for aren’t jobs their negative peers have engaged in,” explained Low.

Youth offenders who need discipline and more structure and support than can be found at home are not necessarily unsuitable for probation. There is another option.

“In the probation order, one of these conditions may include a stay in a hostel,” cited Low.

“Residence in a hostel would take maybe nine to 12 months. And in that period, they’re only allowed to return home generally on the weekends.”

That was the court’s decision after five weeks of investigation into Ahmad’s case. Following two weeks in the Singapore Boys’ Home, he was transferred to a hostel for a 12-month stay, during which he can still go to work.

After that, to monitor compliance with his curfew, he will be electronically tagged with a device for four months as part of eight months’ probation at home.

WATCH: The first episode in full — Don’t put me in jail: How young offenders become probationers (47:56)

VICTIM? WHAT VICTIM?

To stop young offenders from becoming a menace to society again, the Probation Service also tries to reset their thinking by running programmes for them.

Zack, for example, attended a victim impact programme after he was sentenced in August to 27 months’ probation for theft and aiding unlicensed moneylenders. It is a core programme for all probationers.

“We guide them through thinking about the victims — how the victims feel when an offence is committed,” said senior probation officer How Shi Ying. “Then you get them to develop some empathy for the victims.

“Sometimes they may feel that certain offences that they’ve committed or certain actions that they’ve done are justified because they have their reasons. So we get them to think about other people’s perspectives.”

Zack admitted that he did not think about this previously. “I’m quite shocked. I affected a lot of people,” said the 15-year-old. “I regret … committing crime.”

He said a friend of his could not afford to pay a fine for trespass and was in two minds about getting the money through loan shark harassment.

“He didn’t have the balls (to do it). So I said to him, ‘I’ll do it with you,’” recounted Zack.

“When we did it already, I told my friend, ‘Stop lah.’ I didn’t want to get into trouble, because this can get addictive … Then my friend said, ‘Last (house).’ He said ‘last’ (but we) still did (more).”

Zack must now wear an electronic tag and has a curfew from 8pm to 6am. He said he had never thought about the consequences of his actions because “doing something bad was quite fun”.

One of the reasons probationers like him have committed offences is that “they have a deficit in a certain skills”, Low noted.

“They react based on their impulses. And so the core programmes are meant to then teach them certain skills to ensure that their risk issues are addressed and they don’t get into trouble again.”

Zack and his family also attend counselling sessions — facilitated by his probation officer — to work on their relationship. And it took a while for his father “to digest” what had happened to one of his three sons.

“I didn’t expect that it’d happen to me,” said the father. “Because I can say, in our family, we’re all attached (to each other).

“Where did I go wrong with my parenting skills? Maybe there are some areas I lack. Maybe there are some areas (where) I could be better. I do reflect.”

Zack’s mother said: “We made a lot of effort … to get to know him, but he’d just (brush) it away.”

She added that he had “always idolised his friends”, who had links with gangs. And he would not brook any criticism of them from his parents. In the end, he could not resist the negative peer pressure.

“I wanted to be there for friends, but then I ended up being like them … They started asking me to do bad stuff, then I (did),” he admitted.

“I come from a family that’s … not so broken. I don’t know why I’m so broken.”

Only when he was brought to the Institute of Mental Health did they realise there was a deeper issue.

Zack had moderate attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). He was also diagnosed with oppositional defiant disorder; as the name suggests, children with this disorder show “defiant behaviour towards authority”.

WATCH: Teenage anger issues: I became a loan shark runner at 15 (7:50)

“Such children may demonstrate an irritable kind of mood. They usually can be spiteful … And when adults are trying to give instructions, they’d react negatively,” said Teoh.

“Such disorders can result in them seeking risky behaviour (for a) thrill. And because they don’t really think through their actions, and they can’t think through the consequences, it kind of predisposes them to act out in an antisocial manner.”

The ADHD medicine Zack was given has helped, and he does better in school now. “I won’t get distracted or very rowdy,” he said.

Following his diagnosis, his parents also “try very hard to understand him”, knowing now that “he can’t express himself so well”, noted his probation officer.

“One thing that we value is family involvement. If … the family is supportive, the boy would also make positive changes,” she said.

And she saw that change in him when he applied to be a peer leader at school to welcome this year’s Secondary One students.

“In the past, he tried to get respect, or rather, tried to be a leader of a group in a bad way, with his friends who were more of a negative influence,” she said.

“Now … he wants to use that leadership and that desire for respect in a more positive way.”

WHEN A BREACH HAPPENS

While some offenders find redemption, others find themselves facing the music when they breach their probation conditions.

That happened to 19-year-old Zaid, who had forged his teacher’s signature four times in his movement book at school. By signing out himself, he gave himself more time before he returned to his hostel.

He had been given 22 months’ probation for theft, including a nine-month placement in a hostel for probationers. He had also been put under a 10pm–6am curfew. But there has been poor compliance.

“He’s received warning after warning for breaches of the time restriction, failing to attend community service, failing to report to me, failing to attend school as well,” said senior probation officer Dayana Noor Mohamed.

Having been on probation for over a year already, “he should be very familiar with the rules and the expectations of him”, noted a “concerned” Low.

“Breaches like failing to comply with time restrictions or failing to attend school aren’t criminal offences. But they’re a big deal,” said the 37-year-old. “We’re trying to teach them that rules are important. They need to follow rules.

“And, of course, by extension they need to follow the law. So if there’s a breach of probation conditions, then it’s perhaps their lack of motivation to … make positive changes. Also, perhaps it’s a deficit in their skills.”

In the case of Zaid, according to Dayana, his breaches stemmed from his need for a sense of relatedness, most recently to his girlfriend, with whom he was having “relationship issues”.

“So he wanted more time to discuss things with her,” said the officer, explaining the forged signatures. Or, in his words, “to help her because she’s got some problems”.

To help him get his priorities right, Dayana’s sessions with him have revolved around peer refusal skills and decision-making skills. But in situations “where he feels that he’s about lose this person”, he would still take risks, she noted.

For his acts of forgery and breaking curfew, he had to go back to court. But Dayana met him first to try to navigate him around his “self-sabotaging behaviour”.

“I’m not asking you to choose (between the relationship and probation). I’m asking you, how can you handle both? You have to handle both,” she told him.

“Say in future … you have a job and you have a wife. Do you forget about your wife and then you just go to work?”

His reply? “Must have balance lah.”

If his probation order is revoked, the court may send him to the Singapore Boys’ Home for rehabilitation or detain him at a Reformative Training Centre for his original offences.

Reformative training — for offenders aged between 14 and 21, some of whom could have been deemed unsuitable for probation — carries a criminal record.

And in 2019, a fifth of offenders failed to complete their probation, largely because of persistent violations of their probation conditions despite multiple warnings. In these cases, officers would have called for a review of the probation order.

This review is overseen by senior staff. “We look at the circumstances of the breach, how serious the breach is, and we look at the reasons why this happened and whether they’ve done it before,” said Low.

In the end, Zaid received a court warning, with no more second chances.

“I just realised what I can do and what I can’t do,” he said afterwards. “I actually don’t know how to look out for people. If I’ve got a problem, how do I want to look out for people?”

Helping offenders with their coping skills is part of the work of officers like Dayana that people do not often see.

“People have the misconception that we’re just there to supervise, check on their time restriction, scold, scold, scold,” she said. “But a large part of it is (about) going through intervention plans, running the programmes, making sure that they understand.”

Probation officers have “various roles”, said Low. “Some people believe that probation officers are rigid … Some people believe that probation officers, being counsellors, are lenient,” he added.

“We do try to balance that enforcement role with the guidance role.”

REHABILITATING FAMILIES

There are also times when the officers struggle to help and rehabilitate not only the probationer, but also their families, especially when the family problems run deep.

There are times when families fail young offenders, for example when parents find it hard to change their ways, even if the probationer has changed.

That was how Lisa felt after she had stopped taking drugs, quit smoking and was trying hard to win her father’s approval during her 24-month probation for substance abuse.

“Even (though) my urine tests were negative, he’d still think I’m taking drugs,” she recounted. “He’d constantly tell me, ‘Oh, your other friends (are) already at the polytechnics. They’ve graduated.’

“Do I not see that? Like obviously I know that (and) I’m affected by it … By telling me you’re ashamed of me, this and that, it doesn’t help.”

Although she used to go clubbing frequently and her father disapproved of her lifestyle, she was “learning how to change”, noted probation officer J Aswanee, who cited how the 20-year-old found a job and was going to start school.

“She spends time with people who are … working or schooling. (Her) activities have also changed. Recently, she went to paint with her friend at the beach,” said Aswanee. “She’s already trying her best.”

WATCH: Dad, why can't you see I've changed? A probationer's cry (6:51)

Instead of recognising this, the father “constantly” talked about the past, shared his daughter, who did not know what to do to change his mind.

“If I want to be really bad, I could say (to him) … ‘You used to hit me until I bled. You always asked me to go and kill myself,’” she said. “But does ‘last time’ matter or ‘now’ matter?

“I’ve been clean for two-plus years … Have I ever missed a urine test? No.”

Given this strained relationship between parent and child, Aswanee flagged a potential problem: “She might begin seeking relationships with negative peers instead. So this might also mean that she goes back to her old habits … which we don’t want.”

With “no peace” at home, Lisa said she did “seek comfort in friends” — those who “push (her) forward” and not the ones who “continue doing drugs”, as she has cut contact with people who are “just not good” for her.

Because of the fights at home — dating back to Lisa’s teenage years — and lack of family support, Aswanee arranged for her clients to articulate “some of these grievances in a safe environment” and how they could meet each other halfway.

But the session did not go well. “Everyone got emotional,” she said, adding that the father “wasn’t ready to listen” and “kept focusing on (Lisa’s) weaknesses” instead.

“The girl was also crying throughout the session. So we had to terminate the session prematurely.”

Communication was an issue between parent and child.

“Every time we … had disputes, I’d try my very best to mellow out. I’d ask him, ‘Daddy, do you want to go for dinner and then we can talk things out?’” recounted Lisa.

“But he’d want to quarrel on the phone, on WhatsApp … He’d ask me to shut up.”

When Aswanee spoke to him two weeks after the session and suggested “it’d be very helpful” if he began affirming Lisa’s efforts, he acknowledged that he could “do better to have a better family” and needed “to learn”.

“Many times, I use strong words: ‘I’ll disown you … I won’t go and see you again,’” he cited, admitting that he had a temper.

“Is it because I’m … a father and I’m a very tough guy? So words that I use might not help her to change but hurt her.”

Changes in parenting behaviour take time, noted Aswanee, “and we can’t force change”.

Still, change lies at the heart of probation and rehabilitating youth offenders, both on their part and their families’.

“These are their formative years … We want to make sure that we break the cycle early,” said Chu, who also heads the Centre for Research on Rehabilitation and Protection.

“Family does matter a lot … If we can help with the environment, you have a better chance.”

For Lisa, things got better with four months left in her probation. “I’m thankful that the session happened ... My dad stopped talking about the past — completely stopped,” she said.

“Maybe he realised that … other people are telling him (the same thing). The thing about my dad is he needs other people to tell him. If I tell him, he won’t believe me.”

She has tried to understand where he is coming from as a single father of two. “I just always remember he’s my dad, and he’s done a lot of good things for me,” she said.

“He’s been taking care of me since young, when my mum left. He could’ve done the same thing as my mum. But he didn’t.”

She is also “so proud” of herself and what she has achieved during her probation. “I don’t even need anyone to tell me that. I can just tell myself that,” she said.

“I didn’t want (my dad) to think that I’m a bad person … (But) I read this book: It taught me that I don’t have to seek any sort of validation from anybody.”

This is one way Aswanee thinks probation officers can help probationers to face setbacks on their own in future.

“I strongly believe there’s good in people,” she said. “My job is to identify this good and … get them to recognise this good for themselves.”

Watch the series Inside the Probation Service here.