I was kidnapped, tortured and trained to be a scammer. This is my story

Chinese national Lee was walking down the street in Cambodia when he was bundled into a van. He ended up in scam syndicates where he was compelled by threats, beatings, even torture, to do their bidding.

China national Lee was kidnapped and sold to a scam syndicate while walking along the road. He was then trained to be a scammer, compelled by beatings and torture. (Illustration: Rafa Estrada)

Name: Lee (pseudonym), 24

Status: High school graduate from Jiangxi, China

SIHANOUKVILLE: I didn’t know who the men who kidnapped me were. Maybe they’d been observing me for a while. Or maybe I just walked past them at the “right” time.

I’m from Jiangxi, China. I came to Cambodia early last year to work in a Chinese restaurant in Sihanoukville. Every day, I did the cleaning, delivered food, worked at the cash register and did odd jobs to help out.

I worked there for about eight months before I resigned; my contract was expiring, and I wanted to go home.

I left the restaurant with my luggage and passport and headed for a hotel for the night. It was late, maybe 1am or 2am, and I was planning to go to the airport the next day.

I didn’t think too much when a black van pulled up beside me. But when two men got out — one pointing a knife at me — I knew I was in trouble.

They didn’t say much, they just forced me into the van. They put a hood over my head and told me sharply not to move or talk, or else.

We drove for some time before we reached our destination. That was when my kidnappers pulled off the hood and told me I was being sold to a “company” — if I agreed to work for the company, I wouldn’t be tortured.

At that time, I didn’t know how to react, so I agreed. I thought that was the only way to ensure my safety.

Before the company took me away, one of my kidnappers told me: “Work hard at your job, and once you’re done, you can go home.”

I promised to work hard. I just wanted to go home.

WATCH: Lee’s account of how he got kidnappedHANDCUFFED TO A BED

I was in that syndicate for only less than a week.

When I found out what I was going to be doing, I refused. I didn’t want to break the law. I wanted to negotiate a ransom — I thought I’d do whatever I could to get my friends and family to transfer the money.

But I was told I didn’t have a choice and to shut up. I was later handcuffed to a bed, where I stayed for three days without any food or drink. I was also beaten and electrocuted.

At that time, I felt that resistance was futile. I felt so helpless and, at times, considered ending my life.

But I thought of my parents in China. And I was still young, with a whole future ahead of me. So that motivated me to try to save myself.

I was moved to another syndicate in Sihanoukville. It was a big organisation with a hierarchical structure — there were leaders of small groups, leaders of big groups and their supervisors. There were also departments like customer service and human resources.

I was the lowest of the low, for whom regular working hours were 12.30pm to 1am. But everyone started earlier or did overtime, because if you didn’t push for “sales”, you were punished.

On average, my working hours were about 17 to 18 hours a day.

TRAINING TO BE AN ONLINE LOVER

I decided that I’d try to earn the trust of my bosses so I could attempt to get out of this place. I told them I was willing to learn, and they sent me for training.

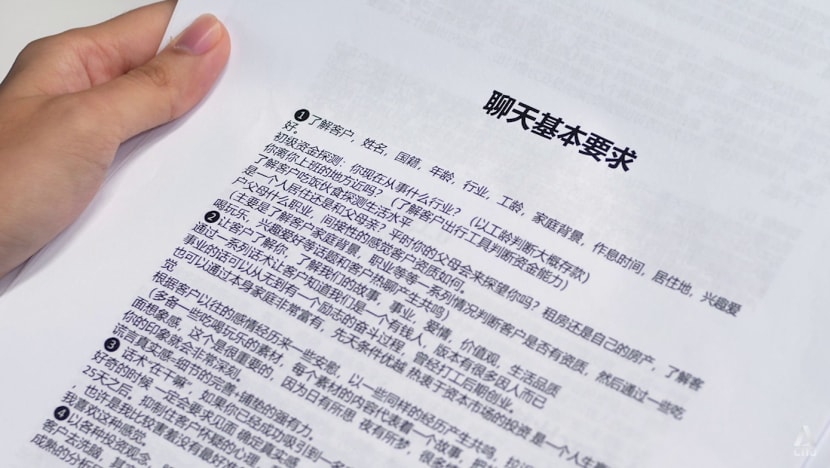

Every day, I learnt techniques for sweet-talking women. I was also given a handbook that covered topics including psychological techniques, how to carry on a good conversation and how to get our “clients” to disclose details about themselves.

The syndicate I was in targeted Chinese-speaking women in Singapore, Malaysia, Australia and the United States.

My supervisors, who believed it was easier to scam women than men, said women weren’t as sharp and were less aware of love scams. Women might also find it harder to get out of a relationship after falling in love.

I remember them saying, “You can lead (her) by the nose, and she’ll do whatever she’s told.” Of course I don’t think this is the case.

I’m not the kind of person who talks much, but the training was thorough and took more than a week, involving three to five different trainers. I also had to watch other people at work and learn from them.

I saw that everyone worked in groups of four and took turns to chat to their victims. If one of them didn’t know how to respond, he’d pass the phone to another or to the group’s leader for help.

WATCH: How Lee trained to be an online lover

Every day, I had to copy from the manual — I was told that was the best way to memorise it. But I pretended to be dumb and slow so I could drag out the training process for as long as possible.

There were times when the trainers tested me on the spot, and if I couldn’t recall the facts, I’d be scolded or made to do squats or push-ups.

Whenever they scolded or beat me, I’d keep quiet and accept it. This was how I managed to gain the trust of my bosses and get my phone back. It had been taken from me when I was kidnapped.

Every night, and during my toilet breaks, I sent out messages to as many people as I could: Friends and family in China, even the police and the Chinese embassy. Using TikTok, I also got in touch with the Cambodia-China Charity Team (an organisation that helps to rescue trafficking victims in Cambodia).

Together with local authorities, they managed to get me out.

Read our two-part investigative special:

NEXT DESTINATION: HOME

That was early December. Since then, I’ve lived in a guest house in Sihanoukville and depended on the kindness of charity organisations that’ve helped me with my living expenses.

After what had happened to me, I was worried about being kidnapped or trafficked again. Because of this, it’s been hard for me to find a job. I’ve been spending my time doing chores and cooking for the other people in the guest house.

I miss my family, and I want to go home. But there are very few flights owing to the pandemic, and tickets are very expensive — as much as US$10,000 (S$14,000) per ticket for a direct flight.

If I really can’t get home, then I’ll try my best to find a job so I can survive here until flights resume and prices go down.

I’m just trying to stay out of trouble as much as I can. And I want to share my story so that others like me will avoid being scammed by fake promises of good overseas jobs with high salaries.

Be realistic and honest with yourself — it’s not as good a life as you think.

As told to Talking Point in April 2022. Since then, Lee has managed to return to China.

Text: Lianne Chia, Cheryl Tan