Even as Malaysia’s schools reopen, children may need help to deal with COVID-19 deaths, trauma

They have suffered during the pandemic, from grief over losing their parents to setbacks in learning. But grit and stoicism are not in short supply among Malaysia’s youth, the programme Insight finds out.

Nur Atiqah Jamaluddin and her three siblings lost their parents to COVID-19 in June.

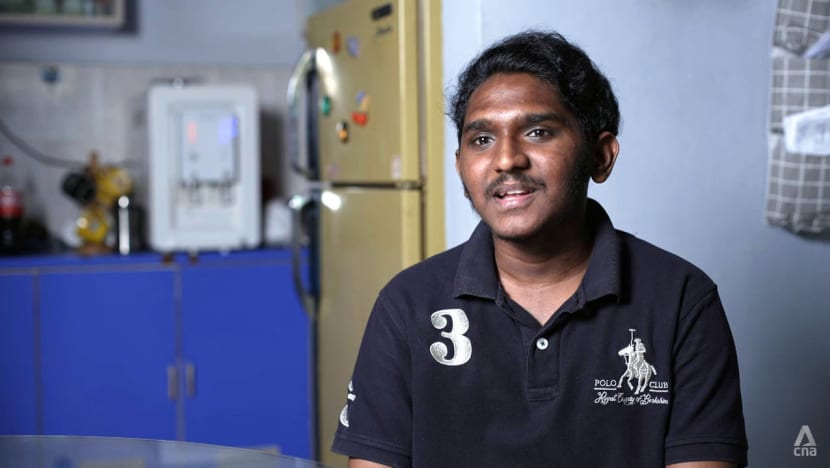

KUALA LUMPUR: Vanjniieswara Thamilselvan graduated from high school just as the COVID-19 pandemic began disrupting life in Malaysia.

He was accepted by a government polytechnic for further studies, but the school was in Ipoh, over 200 kilometres from where he lived. The 18-year-old reckoned his expenses would add up to RM1,000 (S$325) a month.

He could not afford it — not when his father’s job as a lorry driver had been badly affected. From about RM2,000 a month, his father’s income plunged to around RM600 to RM700 when many companies shut and demand for cargo drivers was down. The family got by with income from his mother, who works at a pharmacy.

But Vanjniieswara did not give up.

He wrote to other polytechnics and was accepted by Veritas University College in Petaling Jaya, which was much closer to home. Better yet, his results in his foundation year were impressive enough to land him a scholarship to do a three-year accounting and finance degree course. This meant paying only RM1,000 a year in fees.

“I was shocked upon hearing the news. Only RM1,000? I didn’t believe it at first, then (someone on the phone) explained to me about the FMT-BAC scholarship,” said Vanjniieswara. He was referring to the scholarship established by news portal Free Malaysia Today and the BAC Education Group, whose institutions include Veritas University College.

When he told his parents the news, they were “so happy” because their financial burden would be lifted.

“For higher education, you need more money, right?” his father, Thamilselvan, told the programme Insight.

“We can’t afford to pay that much. Luckily, he got the scholarship. Thank God, and thanks to the BAC’s (co-founder and managing director) Mr Raja (Singham) and his colleagues and lecturers.”

As Malaysia’s schools and economy reopen after a successful vaccination drive and a fall in COVID-19 cases since September, stories like Vanjniieswara’s might offer hope to children who have suffered setbacks and trauma in the last 20 months.

PROCESSING GRIEF, STAYING STOIC

Like in other Asian countries, children in Malaysia have struggled with isolation and disrupted learning amid rounds of school closures. Poorer ones have been more badly affected.

Before the pandemic, there were 2.91 million households in the bottom 40 per cent of the income ladder, with a monthly income of RM4,849 or less. In September, Prime Minister Ismail Sabri Yaakob said the pandemic had caused about 580,000 households to slip from the middle-income category to the bottom category.

Also, absolute poverty in Malaysia went up, from 5.6 per cent to 8.4 per cent last year.

The plight of children in rural areas is worse. They may not have the electronic devices and internet connection for online learning, which puts them at higher risk of falling behind their peers and dropping out of school.

Thousands of children have also lost loved ones to COVID-19. As at the end of September, almost 4,700 children have lost at least a parent or guardian to the coronavirus.

They include sisters Leong Yi Wen and Leong Yi Yen, and college student Nur Atiqah Jamaluddin and her three younger siblings.

You can only be sad for a short while. After being sad, you’ll have to stand on your own feet.

The Leong sisters lost their mother, grandmother and a great-aunt to COVID-19 in June. For 15-year-old Yi Yen, the loss of their 42-year-old mother is still too painful to talk about.

Their father, contractor turned rojak-seller Leong Kwai Kheong, 57, said his wife, Pei San, developed a fever on June 10 and did not recover after seeing a general practitioner. She was tested for COVID-19 only after her condition worsened.

The entire household became infected. Three of them died over a span of four days, leaving only the teenage sisters and their father, who live in Jinjang, a town on the outskirts of Kuala Lumpur.

Leong is stoic in the face of tragedy. “You can only be sad for a short while. After being sad, you’ll have to stand on your own feet,” he said. “If I’m not strong, what would happen to my daughters?”

Nur Atiqah, 19, and her siblings lost both parents in June. Their mother, Siti Sariani Mohd Muzahir, 45, contracted COVID-19 from a colleague who had broken quarantine and attended an annual Teachers’ Day celebration, according to their grandmother Sulimah Sujak.

When Siti fell ill, she went for a swab test and was asked to self-quarantine at home. More family members became infected. Her husband, Jamaluddin Abu Hat, 45, got very ill and was admitted to the intensive care unit. He was placed in a medically induced coma but died on June 23.

Siti was alone in hospital when she received the news. She died three days later.

“I’d already cried so much over my father. When it came to my mother … it was more like, I couldn’t believe it, so I just didn’t cry as much,” said Nur Atiqah, whose family lives in Jenjarom, Selangor. Her youngest sibling, six-year-old Ahmad Munif, is grasping the fact that his parents are gone. He holds on to his parents’ clothes and asks questions like, “Is Mother in heaven?”

Nur Atiqah worries that her younger sister might lose focus on her studies and get poor grades. But their aunt, a teacher, has stepped up to encourage the children. For Atiqah herself, studying is a way to remember how her mother pushed her to “study hard”.

I’d already cried so much over my father. When it came to my mother … it was more like, I couldn’t believe it, so I just didn’t cry as much.

Child psychologist Katyana Azman said the grief at a parent’s death from COVID-19 is compounded when children cannot go out to socialise or receive support from their peers, teachers or community.

Younger children may also find it difficult to process the fact that their parents caught something resembling the flu, then suddenly deteriorated and died, said Katyana of Pantai Hospital Kuala Lumpur. “The biggest thing I’m seeing is that sense of anxiety.”

WATCH: Asia's Lost Generation: Can Malaysia's Children Recover From COVID-19 Devastation? | Insight (47:57)

She applauded the government’s efforts to help affected children but noted that some will fall through the cracks.

The government announced a RM25 million fund last month for the welfare and education of children who have lost parents to COVID-19.

And last week, the Education Ministry announced that it had completed distributing 150,000 digital learning devices to students, contributed by Malaysia’s government-linked companies in partnership with the country’s finance and education ministries.

NON-PROFITS HELPING AT-RISK YOUTH, ORANG ASLI

Like many countries round the world, some semblance of normal life is returning to Malaysia, but experts say there is much catching up to do.

Schools began reopening from Oct 3 based on their state’s COVID-19 situation, starting with students sitting major exams. To reassure parents, the government’s CovidNow website lists the vaccination rates of both students and staff of individual schools. The country has vaccinated most adolescents aged 12 to 17 and is working to procure vaccines for those below the age of 12.

Non-governmental organisations (NGOs), meanwhile, are reaching out to groups such as at-risk youth and indigenous communities.

Before COVID-19, school attendance was already an issue among the Orang Asli, the indigenous people of Peninsular Malaysia.

But when the government implemented the movement control order, many Orang Asli children who had been sent to boarding schools returned to villages where internet connection is limited or may not exist. Parents may not be equipped to help with online learning either.

Some students had no education for several months, according to a November 2020 report by United Nations agency Unicef Malaysia on the pandemic’s impact on vulnerable children and families.

The lack of mobile and internet coverage also affected rural communities’ access to information on COVID-19, leading to a lack of knowledge of infection control and a fear of outsiders.

Rounds of school closures have meant “there’s just no consistency” for students. “We’re expecting … the drop-out rates to significantly rise after this, even if it’s been high already,” said Samuel Isaiah, an award-winning teacher known for his work with Orang Asli students.

As their challenges are “multi-faceted” and “interlinked”, teachers must lead and be social innovators who can help to address problems in the community, said Samuel, the programme director of Pemimpin GSL, an organisation that trains school leaders to improve student outcomes and achievement.

For school drop-outs, non-profits like MySkills Foundation provide a safety net by teaching vocational skills to improve the youths’ chances of getting jobs. The foundation helped 13-year-old Jaishnavii Kishor-Varma, who had dropped out of school at the age of nine because she could not afford the fees.

Her mother abandoned her when she was young, while her father, a barber, was arrested for drug-related offences.

Homeless in the middle of a pandemic, Jaishnavii had to fend for herself until MySkills Foundation took her in. She used to shower in bathrooms at fast food chain McDonald’s but now has a much safer living environment at the NGO’s premises in Kalumpang, Selangor, where she is learning skills like typing.

“(At first at) MySkills, I was so scared,” she said. “After that, they taught me how to study, how to get the best out of (myself).”

Much remains to be done to help children through this unprecedented period of their lives.

Unicef Malaysia education specialist Azlina Kamal said: “There are a lot of things that we need to do in terms of catching up — not just in terms of the learning loss, but also in terms of mental health and psycho-social support (and) helping children to address the traumas of having lived in a COVID lockdown.”

Watch this episode of Insight here. The programme airs on Thursdays at 9pm.