Every day, half a million malware apps are created for scamming. Who’s behind them?

Scam apps can be surprisingly easy to create. The programme Talking Point heads for Vietnam, one of the world’s top 10 cybercrime hotspots, and discovers that the person behind that malware app could be a teen with a computer.

Talking Point host Steven Chia with Nguyen Quang Dong (right), one of Vietnam’s leading experts on digital safety.

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

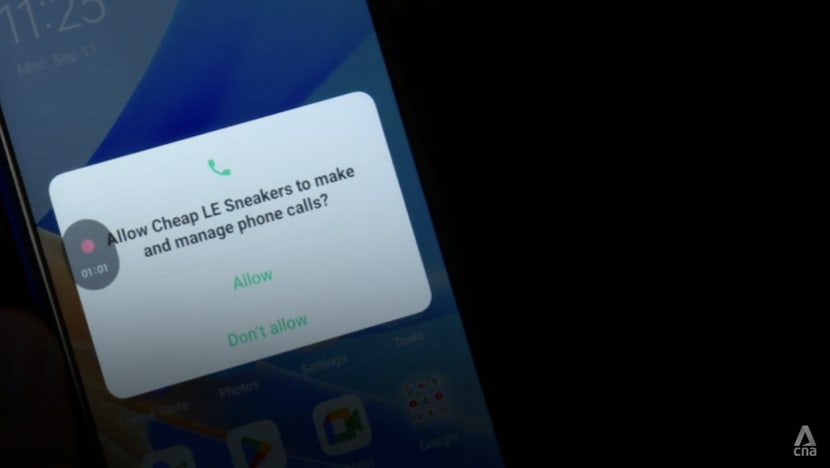

HANOI: One hour. That is all the time it takes to build malicious software that can access the camera, messages, calls, storage, microphone, location, contacts — nearly everything — on a victim’s phone.

And cyber threat hunter Ngo Minh Hieu finds more than half a million of such malware apps created every day, in his work for Vietnam’s National Cyber Security Centre.

Vietnam saw a 64 per cent rise in online fraud in the first half of this year compared with the same period last year, according to the country’s Authority of Information Security.

A growing number of incidents in the last five years are related to malware, said Nguyen Quang Dong, the director of the Institute for Policy Studies and Media Development.

The flurry of fraudulent activity has landed Vietnam among the world’s top 10 cybercrime hotspots according to the Global Tech Council, the programme Talking Point found as it investigated who might be behind the malware scams that have emerged in Singapore this year.

FORMER SCAMMER BECOMES CYBER THREAT HUNTER

Between January and August, more than 1,400 victims in Singapore lost at least S$20.6 million in total, police said.

The perpetrators linked to malware scams have mostly played the role of money mules, said Ang Hua Huang, assistant superintendent at the newly operationalised anti-scam command centre run by the Singapore Police Force.

There have been teenagers arrested for suspected involvement.

WATCH: Who are the people behind malware scams? (21:58)

“These are people who relinquish their bank accounts or even sell their Singpass credentials over job offers on Telegram,” said Ang. This allows scammers to transfer money from the victim’s bank account to a local bank account.

“They’re facilitating the scam syndicates in laundering money overseas.”

The syndicates themselves are usually from neighbouring countries, Ang said.

Over in Vietnam, young people make up the majority of the malware scammers, said Dong, and they mostly operate as individuals.

“Young people here are good at technology. They’re tech-savvy. And some people self-study too. They learn about (hacking) skills,” he said.

Indeed, there is no shortage of tech-savvy individuals in Vietnam — computer science is compulsory in most public schools in Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City, starting from third grade. When students reach high school, coding is compulsory in IT classes.

Today, Vietnam is known to have one of the best high-tech talent pools in Asia.

Hieu himself knows a thing or two about how malware scammers work. He got into hacking “just for fun” when he was 14 years old. When he was 16, he started making money from stealing credit card details, which helped to fund his college education in New Zealand.

By age 23, he was chasing big money: stealing the personal data of 200 million United States citizens from his base in Vietnam. He was caught in 2013 and sentenced to 13 years’ jail.

He was released for good behaviour in 2019 and joined the government to hunt down cyber criminals.

A MARKETPLACE FOR MALWARE

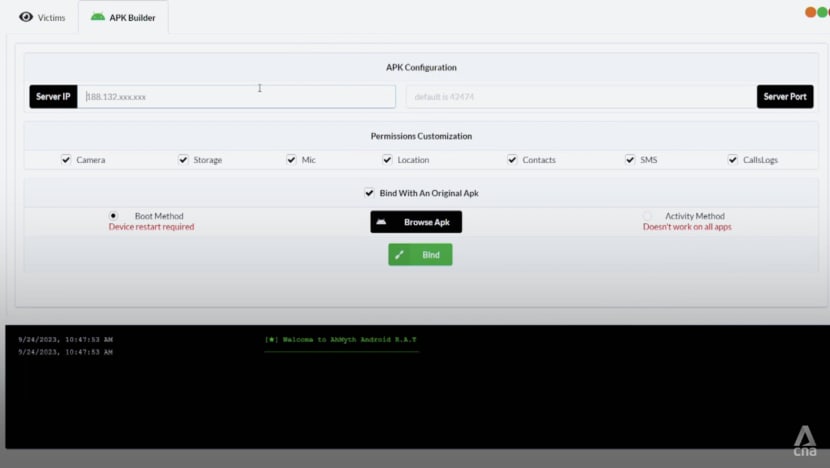

Building malware is so commonplace that there are publicly available tools, known as open source software, that scammers can use to automatically build their app. This is usually the “first step” for most hackers nowadays, said Hieu.

Much like a build-your-own salad bowl, hackers can choose what features they want for their app, such as access to a victim’s messages, and get their end product within an hour.

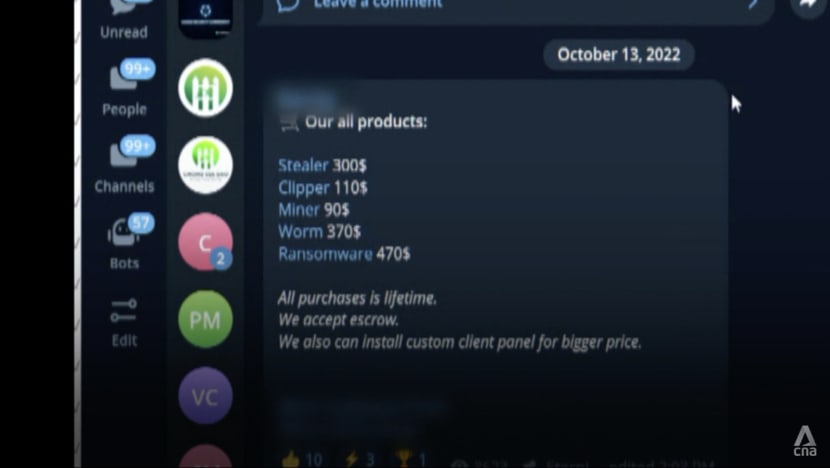

Hacking and scamming resources are also easily found on messaging app Telegram, where developers share tips and tricks.

For those without technical experience, getting their hands on malware apps is as simple as shopping on e-commerce platform eBay, said Hieu. Scammers can use Telegram to subscribe to “malware as a service” or “phishing as a service”, which means for US$300 (S$410) to US$500, they can access the malware of their choice for a month.

There is new malware that can be invisible to antivirus software, said Vu Ngoc Son, technical director at the Vietnam National Cyber Security Technology Corporation. This could mean warning messages will not pop up before a user proceeds to download a piece of malware.

There have also been “high-profile incidents” targeting politicians or certain journalists to steal information, Hieu said. “It costs a lot of money and time to invest or research into these vulnerabilities (on the phone).”

And it could affect Android, Windows or iOS. Anything could be possible with time, he warned. “The phone (security features will) never catch up 100 per cent with the rate of building malware. Each day, I find more than half a million new malware.”

WHAT AUTHORITIES ARE DOING

Vietnam, like Singapore, recently set up a department that focuses on tackling cybercrime.

“We’ve kept ourselves well informed with news alerts sent by either cybersecurity firms or businesses alerting us of hacker groups from Vietnam spreading malware,” said Lieutenant Colonel Trieu Manh Tung, the deputy director of the cybersecurity and high-tech crime prevention department under Vietnam’s Ministry of Public Security.

“There have been a few cases where we managed to … identify the culprits who created and disseminated malware and exchange such information with foreign law enforcement agencies for concerted countermeasures.”

The department has also run cybersecurity surveillance campaigns to “promptly uncover behaviours dangerous to society” and make regular recommendations to the government and civil society organisations on how to raise awareness of cyber safety among the population, added Tung.

“Especially among young people — that the act of using malware to corrupt information systems is a violation of the law.”

In Singapore, the Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS) and the Infocomm Media Development Authority (IMDA) proposed this week a way in which companies and consumers could share losses arising from scams.

If they are found to have breached their responsibilities, financial institutions and telecommunication companies (telcos) may have to compensate their customers who fall prey to scams.

These responsibilities may include the failure of banks to send outgoing transaction alerts to consumers and the failure of telcos to implement a scam filter for SMSes. The framework will focus on phishing scams for a start.

The framework does not include malware scams for now. They are relatively new, and with risk-mitigation measures still being rolled out, it would be “premature” to set out specific responsibilities for the different stakeholders, the MAS and IMDA said.

For example, major retail banks here have rolled out new anti-malware security updates and are looking to introduce a “money lock” feature, which would allow customers to set aside a certain amount in their accounts that cannot be digitally transferred out without strict authentication measures.

Watch the second episode of this Talking Point special here and the first part here. The programme airs on Channel 5 every Thursday at 9.30pm.