‘I want this, a new life’: Jailed 10 times, he eyes redemption — with a boss who believes in him

After being jailed 10 times in 40 years, can he break the cycle? CNA Insider first met Tay Poh Lim behind bars in 2021. Months after his release, we discover what the struggle is like and the reasons for hope.

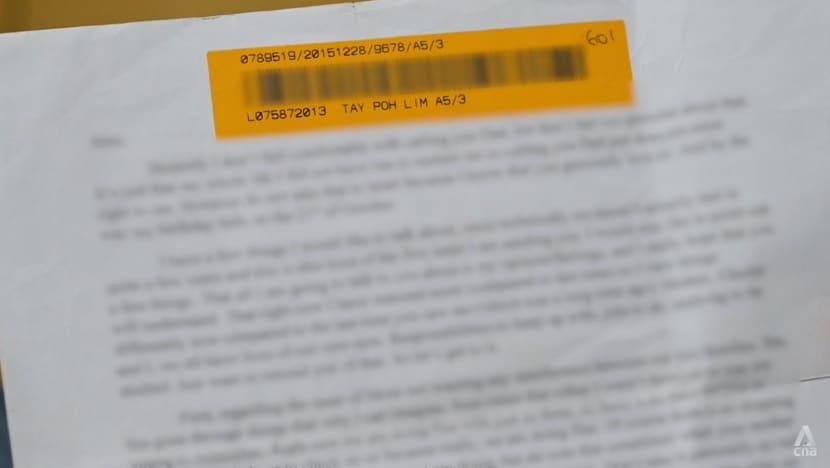

At age 66, Tay Poh Lim has spent more than half his life in and out of prison. (Photos: Abel Khoo, Eileen Chew/CNA)

- Tay Poh Lim did not think he would get a job because of his background.

- One employer, surprised at how articulate the ex-convict was, gave him a chance.

- Adjusting to life outside is a challenge, but there are surprises, like his first plane ride in 30 years.

- He is determined not to disappoint his 88-year-old mother and hopes to be reconciled with his sons.

SINGAPORE: It is barely the crack of dawn, but Tay Poh Lim is already awake, his 66-year-old body accustomed to years of morning drills. When he was in prison, his cell lights roused him at around 6 a.m. every day.

Of all the things he remembers about his multiple incarcerations, this is one habit he wants to keep.

“Early is good. I don’t want to rush my routine. It might get me all agitated,” he says in his usual slow, measured cadences, as he prepares kaya toast and runny eggs.

Agitation is not a good thing. The last time he got worked up about something, simply looking at a friend’s drug instrument was enough to make him succumb to his lifelong addiction.

For more than half his life, Poh Lim mostly slept on a straw mat in cells with up to eight inmates. It is, perhaps, no wonder that the comfort of a pull-out bed, in a three-room flat he shares with his mother and brother, is still unfamiliar to him.

“It takes a while to sort of adjust to the sofa, bed and the air-con and all that,” he says. “Don’t get much sleep lah.”

Over the last 40 years, he has been in and out of prison 10 times. His last stint behind bars lasted five years, after being granted a remission of his seven-and-a-half-year sentence.

“It’s purely my (drug) addiction that continues to bring me back to prison,” he had told CNA Insider in his cell in late 2021, for the video Life Behind Bars.

At the time, the poignant resignation in his eyes as he asked earnestly, “If I tell you I want to change, will you believe me?” moved viewers, including one who would soon change Poh Lim’s life.

WATCH: Life behind bars — in prison for the 10th time (5:56)

Last August, Poh Lim was released and came under the Mandatory Aftercare Scheme for ex-inmates at higher risk of re-offending; he had to wear an electronic monitoring tag for at least three months as well as observe a curfew.

Up to that point, his track record was not great: His shortest reprieve from jail was four months. The longest was a nine-year stretch in his mid-30s to 40s. The drugs always reeled him in.

But this time, the desire to stay clean is more intense than he has ever felt before. At 66, he owes a lifetime of reparation to his 88-year-old mother who visited him in jail each time, pleading with him to change.

Then there is forgiveness to seek from his estranged adult sons, whom he can picture in his dreams “only as little boys”. As age catches up, he is running out of time to rebuild a life destroyed by temptation.

“It’s going to be a lot of effort,” he says stoically.

CNA Insider got a taste of what this meant, when we caught up with him nearly four months after his release. Over two weeks, we learnt how he was trying to make good on his vow — and why, this time, he just might succeed in turning his life around, with the help of an angel or two.

THE UNEXPECTED EMPLOYER

By about 7am, Poh Lim gets ready for work. He picks out a blue shirt and light grey jeans that comfortably cover the GPS tracker strapped to his ankle. “It doesn’t really bother me,” he says. “But others might think otherwise lah.”

Mum, whom he shares a room with, is awake. He hugs her gingerly. “Just call me if you need anything hor,” he tells her.

“One of the pleasures that I have is hugging my mum when I go out,” he tells us. The years of physical separation seem to have kindled a compulsive need to check in with her; besides the hugs, Poh Lim video-calls her several times a day when he is out.

On the bus to the train station, he pulls out his Oppo phone and plays Despacito, then A Million Dreams — songs to start the day in a positive mood, he says.

Eighteen MRT stops later, we near his workplace in Pioneer. He works as a trainee technician in a lifting and engineering company — his first full-time job in 30 years. (His last position, in 1993, was that of graphic designer.)

The new job, which he started just a few days after his release, was unexpected, to say the least. Poh Lim had failed all his O-level subjects and effectively had no track record in stable work at what he called his “frail” age.

When he first spoke to CNA Insider in prison, he seemed resigned to the dearth of jobs for people like him.

But Marc Lee was one of those who watched the video. And the boss of Pro-Lifting Solution was surprised at how articulate Poh Lim was. “(I thought), could this be staged?” he laughs.

The very next day, he wrote to the Singapore Prison Service (SPS), asking to meet Poh Lim.

Marc was looking to hire and had been considering the Yellow Ribbon programme. “I’ve always thought of giving them a second or maybe a third chance. If we don’t start the ball rolling, nobody would, you know,” he says.

What surprised the 47-year-old boss during the Zoom interview was that Poh Lim was exactly as he came across in the video story: polite, with a positive attitude.

(Poh Lim ascribes his command of English to all the reading he did behind bars. To practise speaking, he even read aloud when nobody was around. “You can’t just be starting things when you get out,” he says.)

Marc hired him. And by the time we caught up with Poh Lim last month, he was just completing his three-month probation.

The company’s signature product surrounding his job is a lawnmower called the Spider, which he learnt to operate and repair from his younger colleagues. They would often be found at their clients’ premises, sometimes in scorching weather, tinkering with the battery or gearbox until the machine works again.

Although Poh Lim struggles to lift heavy parts or operate his laptop, the team is happy to help. They also look out for his health, colleague Teh Hang Ming says, as Poh Lim sometimes has headaches.

“Although he may not fully understand some work processes, he doesn’t back off. He’ll keep wanting to learn,” says Hang Ming, who is often paired with Poh Lim for assignments.

What Poh Lim loves about the job is not so much the actual work as the people around him. He lights up as his work chat group comes alive. “It’s good to be one of them,” he says with a laugh.

He remembers how “exhilarating” it was to be added. “I felt that I belonged. They’ve accepted (me), and I’m part of the group,” he says.

The sense of acceptance and the structure of a job with responsibilities are important for someone like him who is battling the demons of temptation.

“When you’ve got a positive structure, you tend to filter out what’s not important,” he says. “My focus is on my family, my mother, my work, and the rest, of course, will fit in with time.”

At lunch, he gives Mum a video call. She tells him she brewed Chinese medicine for his cough. He tells her to eat well for lunch.

“I want to be accountable. So whether I go to church, whether I go shopping, I always video-call her, turn the phone around, show her where I am,” he says.

“But the main thing is to let her know that I care, and I don’t want her to be worried about where I am, so that we can build this trust.”

WATCH: Life after prison — my fight to stay clean after 40 years (20:28)

THE LONG, TIGHT HOLD OF DRUGS

For most of his life, Tay had looked for a sense of belonging in the wrong places.

“After National Service,” he recalls feeling, “there was this loss in direction. There was this void that needed to be filled.”

Drugs, parties, girlfriends, joyrides and petty crimes — when you put rubbish into that void, he says, it burns up your whole life. He was first arrested in 1982 at age 26.

In fact, it was his mother who called in the Central Narcotics Bureau.

“I gave them the time and date … (to) come over to wait for him,” Mdm Lee recounts in Mandarin. “That heartache is beyond describing. It can’t be avoided.”

He was sentenced to six months in jail first time round, nine months the second time round, and after the third arrest, it was a year and a half, she recalls. “By the fourth time, I didn’t want to remember it any more.”

Poh Lim himself barely remembers the details of his arrests; they were always a blur to him. The best years, however, were from 1991 to 2000, when he stayed clean and built a life with his then wife. They met when he was at a halfway house, where she was a volunteer.

“She thought I might just be that one who’s different,” Poh Lim says. “But I’m not.”

They had two sons. All was well at home until financial problems set in, and he relapsed. In 2000, he was caught consuming drugs and sentenced to seven years of preventive detention — the first of three long jail times to come.

His wife divorced him and left with their two sons, who were barely four and six. But the drugs had numbed his conscience. “Nothing existed outside. Not the children, not my wife, not my career,” he says.

It was just me and my addiction.”

After the divorce, he wrote his children cards when he could, never mind that there was no reply.

The only letter he ever received was in 2014. His younger son detailed how the “absence of a father figure” had given him much grief. “I thought I could get over it. But up till now, I haven’t. And I’m extremely tired because of this,” the letter went.

“I don’t know how to solve this. I don't know how to get over it.”

Poh Lim hopes that one day, he will be able to meet his sons in person and apologise to them.

“When I have dreams, I only see them when they’re little boys. And now they’ll have grown so tall,” he says, holding back tears. “Chiefly, I think, I want to tell them that ‘Dad is sorry for not being there for you’.”

AVOIDING TEMPTATIONS

As a former drug offender, Poh Lim is required to take urine tests for up to two years. Currently, he must keep to a weekly schedule.

On the Monday that we accompany him, the tension on his face is visible as he approaches Tanglin Police Station. It is not the test, however, that he fears.

On a visit here prior to his last incarceration, he had bumped into an “old friend”. One thing led to another, and Poh Lim ended up back in jail.

“You just go blank that moment when you don’t know whether you’re going ahead or slowing down, or should you beat the red light,” he says.

He learnt his lesson. On this day, he does meet another friend at the testing centre. But “I just said hello and had some casual conversation — I waited for him to leave after that”, he tells us when he meets us outside.

“It’s best to keep it sweet and short, just in case this conversation carries you to another parameter.”

Then, there are the very few friends he seeks out, the ones he trusts. Every Friday, he catches up with Dennis Oh. They first met at a halfway house some 20 years ago.

“Sometimes I’d meet him in jail, which is sad,” Poh Lim says as we make our way to Geylang Bahru Market and Food Centre. “I don’t have many friends. And I think we have to be very selective about friends because they’ll make or break us.”

Dennis has been on his drug recovery journey for almost two years now. Both are careful to steer clear of places like Geylang, where “triggers” hide in plain sight.

Gesturing at Poh Lim, Dennis, 50, says: “When he’s feeling stressed, or I’m feeling stressed, we’d have these kinds of triggers, where it’d be like, ‘We’ve got somebody I can actually call and get the stuff (drugs).”

On this “chill” Friday night, however, there is no stress. The friends talk about the mundane things, like how to top up their ez-link cards with rewards points.

TRYING TO FIT IN

Those who have spent considerable time in prison often speak about grappling with the changes in modern city life and trying to fit into human society again.

Poh Lim, for instance, on his way to work would rather take the more “lonesome” path along a greenery-lined canal instead of the well-used pedestrian walkway. He prefers to avoid crowds.

He admits he found it “very scary” when he first walked into an MRT station after he was released. “That’s how our society moves,” he says, pensive. “I’m so surprised every time I walk into the MRT — such big crowds.”

Building new relationships remains another challenge.

A Christian since young and a Roman Catholic now, Poh Lim feels “at home” in one-to-ones with his religious counsellor, who helped him reconnect with his faith while he was serving time. Bible study sessions on Thursdays, however, are a different matter.

His church mates do not know he is an ex-convict. And on Sundays during Mass, he sits on his own, and afterwards slips away.

“I don’t have people like you I can talk to,” he tells his counsellor at one of their meetups. “There’s no sense of belonging.” The counsellor advises him to give it time.

On Saturdays, Poh Lim goes shopping. It is his designated “me time”, he says. “To reward myself for handling another week well.”

On the day we meet him at ION Orchard, he makes a beeline for Shake Shack. He had read about the burger joint in a magazine while in prison, and he wants to treat himself to something special today.

The self-ordering kiosk is the only thing standing between him and his burger.

After a failed attempt at making payment — “Nets … Flash … payWave?” he murmurs in bewilderment — he gives up and heads to the cashier to order a black truffle burger, fries and lemonade.

He shrugs it off. “I’ll learn from the mistake,” he says. “Probably won’t embarrass myself next time.”

After his meal, he checks in with his mum as is customary. “It’s only 11am. Where have you wandered to?” she asks in Hokkien over the phone. It is clear she worries constantly that her son might be “wandering” in search of drugs again.

In answer, he points the camera at his now-empty tray. “If I really wanted to wander, I wouldn’t wait till today,” he retorts with a tinge of annoyance.

“You’ve been out for only three months,” she replies. “It’s still a short time.”

She is right.

GIVEN WINGS TO FLY

Poh Lim would be the first to acknowledge that the road to recovery is long, and perhaps never-quite-ending for an addict.

But already, a few things are different this time, with some key factors in his favour.

That is made clear when he steps inside Changi Airport at 5 a.m. on Dec 19, backpack in hand and awe written on his face as he looks round.

Today he will set foot in a plane for the first time in 30 years — on a business-cum-training trip to Kuala Lumpur that his boss is entrusting him with, no less. “Without the job and Marc himself, all this wouldn’t be possible,” he says.

To make this happen, Poh Lim had to meet certain conditions. His company had to first apply to the SPS and the Central Narcotics Bureau for permission for him to get his passport and travel overseas as well as temporarily remove his ankle tracker. He would be retagged on his return.

To Marc, the extra hassle was worth it, to reinforce to a valued employee — whether ex-offender or not — his worth.

“My plan for Poh Lim for the next two to three months is for him to travel quite frequently because we’re expanding our business to the Philippines, Indonesia and Malaysia,” says Marc, who has already expanded Poh Lim’s job scope and given him a pay rise of S$200.

Even at his age, he has proved that he dares to try new things, like take up a construction course and climb 60 metres onto a roof.

Poh Lim is “very happy” about his new responsibilities. “I’m looking forward to the new challenges,” he says. “I need that kind of structure to keep me focused.”

The word “structure” is one he repeats again and again in the time we spend with him — like a mantra, a reminder to himself of what he must stick to.

A year ago, before he stepped out of prison, he lacked the confidence that his life could be much more than a revolving door.

But now, motivated by his desire to put matters right with his family and by the trust of his boss and colleagues, he is determined to do better.

“On a scale of one to 10 for staying clean, I’d give myself eight,” he says. “I’m adding a lot of new activities to my life, (so) that I can move from eight to maybe eight and a half, and eventually I’ll get nine.”