Producers of Separation: Declassified reveal what it took to retell Singapore’s split with Malaysia

For months, producers combed through “hundreds of letters” for little-known details about Singapore’s split with Malaysia in 1965. The team behind Separation: Declassified open up on how they created the series.

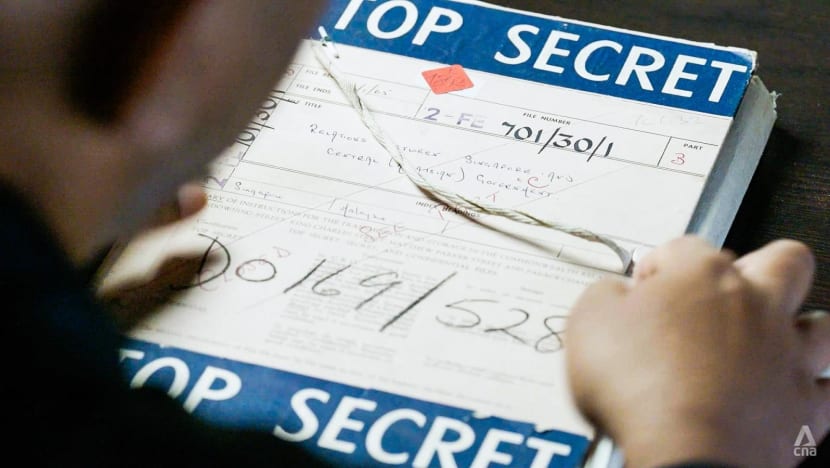

Albert Lau, an associate professor of history at the National University of Singapore, inspecting a miniature set of Singapore’s first prime minister, Lee Kuan Yew, in Sri Temasek the night before the separation from Malaysia.

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

SINGAPORE: When Singapore separated from Malaysia, there was a particular country that was happy with the turn of events: Indonesia.

So happy that one Indonesian diplomat “found it hard to conceal his glee” when he met the British ambassador in Jakarta on Aug 9, 1965.

“(He explained that) Indonesia had always said that Malaysia was not a viable entity, and this was now proved,” the ambassador wrote back to London. “Indonesia could say to the United Nations, ‘I told you so.’”

The telegram was part of a “trove of information and secrets” that surprised a CNA team when they first laid eyes on declassified documents — locked away in Britain’s National Archives — on the historic split.

Such telegrams “were never really meant for the public eye when they were written, essentially”, noted producer Clarisse Goh. “It’s almost gossipy.”

Six decades later, those documents take centre stage in CNA’s two-part documentary, Separation: Declassified, which premiered this week.

“So much of history is presented through documents that have, in a way, been through a kind of filter,” said Mark Frost, co-author of Singapore: A Biography. “You get public speeches, you get official documents, carefully formulated to record events.

“Here you get these telegrams, confidential correspondence, which are all without that filter.”

But that is only one part of the documentary, shared the producers as they opened up on what went into its making.

WATCH PART 1: Secrets, betrayals — How Singapore’s split with Malaysia was engineered (46:59)

WHAT INSPIRED THE SERIES

The spark for the series came two years ago, when CNA producers were digging through declassified British files for a separate docuseries about Singapore’s reserves.

If those files existed, the team reasoned that there would be “so many others” waiting to be uncovered, said Goh. And so they ended up combing through “hundreds of letters”, cables and reports written around the time of the separation.

“Most Singaporeans … think that we were booted out of Malaysia,” said producer Peh Yuxin. “But then every single piece of information that we got from the letters … told us that it wasn’t so simple.”

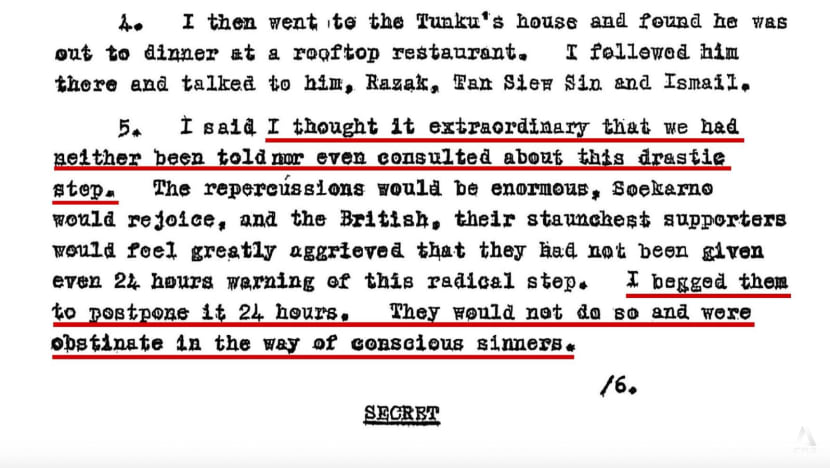

That the British expressed “such helplessness” upon finding out about the split at the last minute was also “a shocker” for Peh, who cited correspondence dated Aug 8, 1965.

With eyewitnesses to this chapter in history becoming increasingly scarce, the producers felt a sense of urgency in revisiting Singapore’s independence.

“Most people who were involved (directly) are just not around any more,” said Peh. “This story was kind of slipping away from us already.”

WHAT WENT INTO THE RESEARCH

With all the research needed, the team decided to frame the story around a 100-day window, starting 70 days before the separation announcement. That gave them space to track the build-up to the split and its immediate aftermath.

“We just went through (the pages) one by one, and then we tried to piece together a story,” said Peh. “It wasn’t easy.”

Usually, research for a documentary takes a month. But in this case, it took close to three months. The team looked for anything that surprised them or added to their understanding of the separation, she added.

Her fascination lay in the candid voices in these reports. In one telegram, a British official compared Malaysian Prime Minister Tunku Abdul Rahman (“the old feudalist”) with Singaporean Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew.

“That was very fun for me,” said Peh. “You think you know Lee Kuan Yew a lot, but then have you ever thought of him being described as the ‘socialist intellectual’ (by the British)?”

WATCH PART 2: How Singapore navigated high-stakes politics after split with Malaysia (46:56)

There were also personal letters that stuck in their minds. “I feel like Death. Tears, heartbreak and completely lost and betrayed,” wrote Donald Stephens, the then chief minister of Sabah, in a letter to Lee dated Aug 10, 1965.

That letter about the separation was “very raw”, reflected Goh. “It almost felt too personal to read.”

DESCENDANTS LEND INSIGHT

As this was CNA’s first docuseries on Singapore’s separation from Malaysia that was grounded in declassified material, the team consulted experts to help fact-check and contextualise what was discussed in the cables.

The producers also interviewed descendants of key political figures, who lent some insight into their relatives’ mindsets during that period. For example, the Tunku’s grandson, Tunku Muinuddin Putra, offered a qualifying perspective on his grandfather’s stance on a multiracial Malaysia.

“He did tell me it’s not that the Tunku didn’t believe in a Malaysian Malaysia,” said Peh. But because the Tunku was “facing pressure” from his party’s hardliners, “he felt that it wasn’t the right time”.

The series also featured Simon Head, son of the then British High Commissioner in Malaysia, Lord Antony Head.

He discussed, among other things, a telegram from the Commonwealth Relations Office that described Lord Head as “Lee’s godfather”. This phrase, said the younger Head, implied his father was “strongly biased” towards Lee rather than the Tunku.

“(Simon) talks about how in (Lord Head’s) heart of hearts, maybe he … preferred Lee Kuan Yew, but … he was always fair,” recounted Goh.

What the producers tried to do was “humanise the historical figures” and “tell people who these people are”, added Peh. “That’s something we tried to do a bit differently (with this series).”

HOW IT WAS PUT TOGETHER

Then came the challenge of translating the emotions and moments in 1965 into on-screen action.

Many of the locations no longer existed or were out of bounds, said Goh, who wondered: “How can we make … something that everyone can see for themselves?”

So the team commissioned miniature dioramas and took more than three days to shoot those scenes. Photographs and other archives were used to piece together the layout of certain rooms and make the sets as historically accurate as possible.

Still, the producers had to re-create moments from scant descriptions, for example having to decide where Singaporean ministers Toh Chin Chye and S Rajaratnam might have stood during an argument with Lee.

“Were they fighting at the foot of the stairs or fighting in the living room?” cited Goh.

The sets served to invite viewers into moments “frozen in time”, said Goh. Rather than risk over-dramatising scenes through re-enactments, the team wanted to create “a sense of mystery” and leave viewers with “room for imagination”.

The producers also hope viewers will feel how they felt in making Separation: Declassified. “It’s like finding treasure,” said Peh — treasure that now belongs not only to diplomats and historians but all Singaporeans.

Watch the series Separation: Declassified here — Part 1 and Part 2.