‘Scholars’ and ‘farmers’: What’s the state of meritocracy in Singapore’s workplaces?

Do scholars get fast-tracked to the top? Has society allocated too much reward for those with exam-passing ability? The series Measuring Meritocracy asks how we can value skills mastery and accord more workers decent pay.

Service engineer Mohamed Hannifa (left) and a colleague supervising a cleaning robot created by LionsBot International.

SINGAPORE: His mother was a cleaner, and Mohamed Hannifa now works to empower people in her industry.

As a service engineer at LionsBot International, which makes cleaning robots, the 28-year-old teaches cleaners how to use and maintain the company’s robots. He has also been sent abroad to train technicians and dealers.

“He’s very adaptable,” enthused LionsBot chief executive officer Dylan Ng Terntzer. “He’s willing to put in the hours — the hours of travelling on the road, the hours of support over the phone, late into the night.

“And he’s able to take the stress of facing customers when, sometimes, things don’t go well. So all this helps to mature him and (take his work to) a different level.”

Seeing his mother return home with body aches over the years made Hannifa feel he should do something “meaningful and help her ease her burdens”.

Robots can take over tasks such as floor cleaning, which could make up about 60 per cent of the daily work, allowing cleaners to “focus on the finer points of cleaning”, like high dusting, disinfecting and customer service, said Ng.

“They can do more tasks. Because of that, they can command higher pay. The cleaner is the supervisor of all these robots, deciding the schedule, the workloads,” he added.

Hannifa, who has a diploma in mechatronics engineering, never thought he would end up in customer service. After joining LionsBot nearly two years ago, however, “I started loving my job”, he said.

“Once you find your area of interest, stay there, work hard and start growing.”

What has also grown in recent years is discussion on what meritocracy means in Singapore’s workplaces. The series Measuring Meritocracy examines the impact of trends such as a growing proportion of workers wielding degrees and asks how society can value skills mastery and accord more workers decent pay.

WATCH: Meritocracy at work in Singapore — how relevant is it today? (45:51)

NUMBER OF CLEANERS IS SHRINKING

Cleaners remain among the lowest-paid workers in Singapore, despite governmental support for uplifting their wages and roles.

But there is something people may not know about the profession. “The secret is, there aren’t many cleaners left,” said Ng.

There were about 55,000 cleaners in Singapore as at November, of whom 41,200 were citizens and permanent residents, according to the National Environment Agency. A decade ago, the reported number of cleaners here was 70,000.

Cleaners are also becoming higher skilled — in several years, they may become more like facility professionals who have been trained in security and landscaping besides cleaning, Ng reckoned. They would all be assisted by technology and robots, he said.

“The aspirations of the young have risen, and we must meet their aspirations,” he said.

From a meritocratic point of view, being (a) facility professional means you get to learn a lot more. And you don’t get pigeonholed.”

“They’re not just doing a cleaner’s job, but they’re more of a robot operator. In this way, they might feel more empowered,” said Hannifa. They could become more tech-savvy in other areas of their lives in the process, he added.

‘RESENTFUL AND ALIENATED PEOPLE’

Although many jobs such as cleaning do not require a degree and remain essential to society, the salary gap between graduates and non-graduates has grown.

The median pay of university graduates is now more than twice that of Institute of Technical Education (ITE) graduates. Between 2016 and 2021, the median starting salary gap between the two groups grew by S$300, while that between degree and diploma holders grew by S$200.

“We’ve allocated too much reward and prestige to just one form of human aptitude … the kind of exam-passing ability that some people have,” said David Goodhart, author of the book “Head, Hand, Heart: The Struggle for Dignity and Status in the 21st Century”.

“That has unbalanced our societies in some ways.”

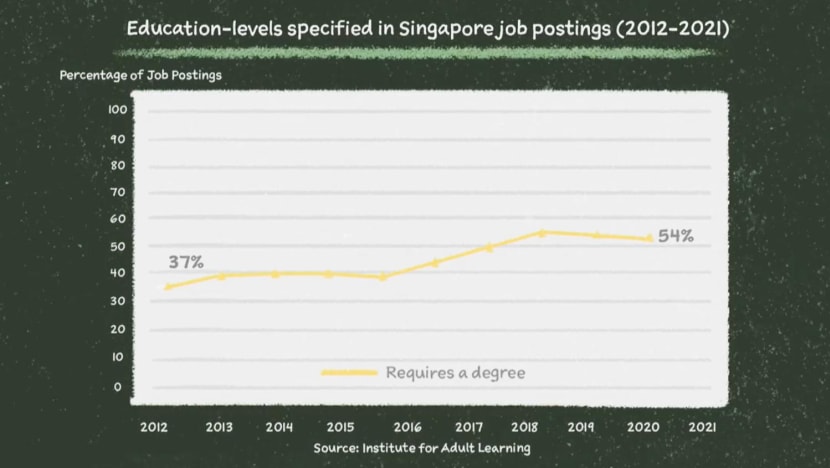

The proportion of job vacancies in Singapore open only to applicants with degrees is increasing, which has been observed in many advanced economies, said Sahara Sadik, assistant director of research at the Institute of Adult Learning.

Commenting on the trend in Britain, Goodhart said: “This is completely the wrong direction. We’ve overshot in the production of academic skills, and we’ve undervalued many of the functions that are absolutely vital for a good society.”

This creates two groups of “resentful and alienated people”: Those who do not go to university at all and people who do but do not get the “elite professional jobs” they had hoped for, he said.

Those without degrees feel undervalued in society; this creates a political problem that has been “one of the drivers of populist politics”, he added.

Calling England an “extreme instance of a meritocratically bifurcated society”, Yale Law School professor Daniel Markovits cited the “populist uprising” seen in Brexit, the United Kingdom’s exit from the European Union.

“People with elaborate elite educations wanted to stay in the EU. People without those educations wanted to leave.”

In the United States, the election of former president Donald Trump “tells exactly the same story”, said Markovits, author of the book “The Meritocracy Trap”.

Given these developments, it is important that Singapore remains an “open, inclusive society where social mobility is alive and possible, even for those who start out as very poor in life”, said Institute of Policy Studies deputy director (research) Gillian Koh.

MIDDLE-CLASS WAGES WITHOUT ‘ELABORATE DEGREES’?

Yet, some shortcomings of meritocracy — where advancement and economic rewards should be the result of talent or effort, instead of family background or connections — are clear even before one enters the workforce.

Parents who have achieved positions of advantage “mobilise their social networks” to help their children secure valuable internships, opportunities that would not be open to students who are the first in their family to graduate from university, said Koh.

“So can we think about how meritocracy needs to be complemented by other methods and programmes so that these kids gather the right work experience (and) useful contacts, so that when they finally graduate, they have as much chance (to get good jobs)?”

A solution, said Markovits, is to restructure the labour market so that people do not require “elaborate university degrees” to be able to get good jobs.

The Europeans are “very good” at traditional trades and guilds, “so that you can, in Germany, have a very good job as a glazier or an electrician or a plumber”.

“An ordinary person can’t walk … off the street and already know how to do it,” said Markovits. These are crafts done by people who have had “serious training” but not degrees, “and they’re paid middle-class wages”.

In Singapore, such roles could be in nursing, for example, or port operations. While more nurses now have bachelor’s and even postgraduate degrees, Singapore General Hospital advanced practice nurse Tan Hui Li said nurses without a degree “can still do their job well”.

“Besides the education, caring and doing it (well) comes with experience,” she said.

Over at port operator PSA, service engineer Syed Muhammad Fayyadh recently earned his work-study diploma in port automation technology. The course introduced him to software and new technologies that can apply to automated guided vehicles — skills in line with future port operations.

THE MILITARY ELITE AND PUBLIC SERVICE

When it comes to ensuring equitable opportunities at work, a big question is whether the government, as Singapore’s biggest employer, is setting the norm. Here, the career paths of scholarship awardees including the military elite are often scrutinised.

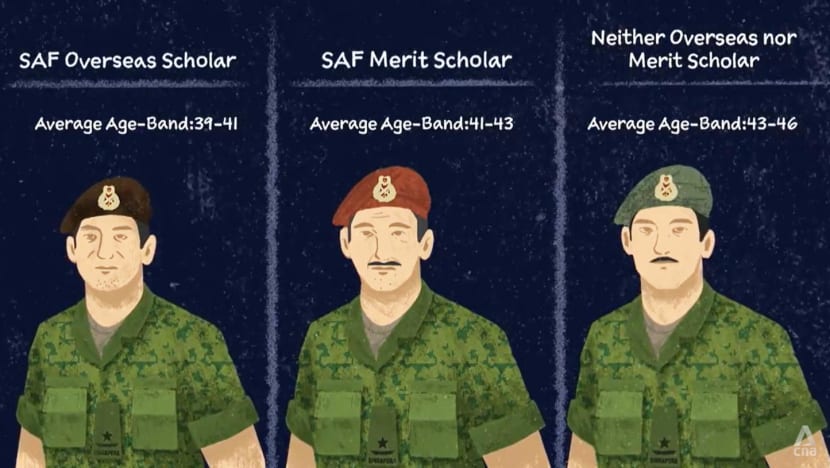

Based on empirical evidence, scholarships do provide a “springboard” in the Singapore Armed Forces (SAF), said Samuel Chan, author of the 2019 book “Aristocracy of Armed Talent: The Military Elite in Singapore”.

He found that someone who had been awarded an SAF Overseas Scholarship (now known as the SAF Scholarship, second in prestige only to the President’s Scholarship, according to the Ministry of Defence) would probably get to the “one-star” rank of brigadier general between the ages of 39 and 41.

“The next tier down”, those who were awarded the SAF Merit Scholarship, usually get there a year or two later, he said.

And those who were neither an overseas nor merit scholar usually achieve the rank between the ages of 43 and 46.

“That shows you roughly the advantages of the scholarship,” said Chan, who considers the military elite to be one-star generals and above. “I’d say they’re set apart from the rest of the officer corps.”

A scholarship does not “guarantee success”, however, and performing on the job is non-negotiable, he said.

Former head of the Civil Service, Lim Siong Guan, added: “Not every SAF scholar gets to be a general; not everybody even gets to be a full colonel.”

Questions have also been raised about the relevance of a military career to some high-level corporate or public service appointments that some retired officers get.

Meritocracy works best where there are “clearly defined goals that are objectively assessed”, said National University of Singapore associate professor of philosophy Loy Hui Chieh.

But in an environment where “the questions are more open-ended, where it’s no longer a straightforward matter of … winning a war but rather, for instance, helping Singapore upgrade itself … it’s no longer so clear-cut that there’s a straightforward metric we can select for,” he said.

To Chan, however, “it’s not simply (that) you get a cushy job because you served in the military”.

“We need to understand the big scheme of things,” he said. Generals have “lots of responsibility” and oversee budgets that can amount to “hundreds of millions of dollars”.

Because of the relatively early retirement age of 50 for SAF officers, “it’s in Singapore’s interests to be able to use their talents and deploy them somewhere else, where they can help society”, he said.

In the wider public service, scholarships are a way of identifying leaders, said Terence Ho, an associate professor in practice at the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy. “But it’s important that this isn’t the only route.

“It’s important to ensure that the so-called ‘farmers’, or those who don’t come through the scholarship route, would also have sufficient opportunity to learn, grow on the job, demonstrate their potential and eventually also rise to the top.”

“Scholars” and “farmers” are terms borrowed from Imperial China, where magistrates were scholars who ruled over farmers, said Loy.

For years, Singapore’s public servants have been identified for progression based on their Currently Estimated Potential (CEP). But the in-joke is that CEP stands for “career ending point”.

In 2020, Minister-in-charge of the Public Service Chan Chun Sing said the CEP system would be updated, as the career road map should be for public officers’ next three to five years, not their next 30 years.

“We’ll also update how we assess high potential. To show leadership potential, we must not only be able to make sound policies (but also) be able to implement well, innovate, work in teams, communicate effectively and mobilise relevant stakeholders for collective action,” he said.

Lim told CNA: “I’d like to believe that every time we appoint anybody to any appointment, whether civilian or military, we’re just trying to get the best candidate that (we) can, whom (we) are aware of.

“You hope most times you do a good job of it. … Sometimes the decisions could be better.”

No system is perfect, he added, and Singapore works on areas where it is “not doing well enough”.

REGARDLESS OF AGE, DISABILITY AND MORE?

Over in the private sector, it is difficult to police the provision of equal opportunities, Koh said.

But there are guidelines from the Tripartite Alliance for Fair and Progressive Employment Practices, and these will be made into law. The guidelines include hiring based on merit and regardless of age, race, religion, marital status, family responsibilities or disability.

There are funds and grants to help companies be more inclusive, but firms must have “a more open mind” and give individuals the opportunity to “show what they can bring to the table”, said wheelchair user Kishon Chong, a customer experience and inclusivity officer in transport company Tower Transit.

There is also bias that is sometimes unconscious.

Research by the global non-profit Generation — which helps to improve employment outcomes for underserved workers — found that an “overwhelming majority” of hiring managers perceived younger job candidates to be a “better fit” for certain roles, said Prateek Hegde, the CEO of Generation Singapore.

“However, when we asked them about on-the-job performance, they all agreed that the mature workers were performing on a par with the younger workers.”

Ultimately, even if a society believes in meritocracy, “you want other principles to balance it”, such as social justice, said Goodhart.

“There’s every threat that the concept of meritocracy will cause those who progress to be puffed up and to say, ‘We deserve our position, and why can’t everybody else put in the same effort as I did to arrive where I am?’” said Koh.

But Singapore is “too small” to afford such a division, she warned. “The smaller we are, the more we should realise we need one another so much more.”

Watch this episode of Measuring Meritocracy here. And read about how to keep meritocracy a driver of opportunity in schools here.

_1.jpg?itok=Pt4lopXb)