Thailand is one of the world’s fastest-ageing developing nations. This is how it happened

The kingdom’s population may halve before the turn of the century. The programme Insight delves into the reasons, and the possible solutions to a fertility decline that poses unique challenges.

The Thai government is changing laws to encourage more births.

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

BANGKOK: It has been four years since Sira Kitpinyochai and Boontarika Namsena exchanged wedding vows, and they are happier having 11 cats than they would a child.

The couple agreed to forgo parenthood before getting married. As they saw it, “children (were) more like a burden because of all the expenses involved”, plus a needless appendage to their already uncertain financial plans for old age.

Then there is their lack of time. “It’s mostly 10 to 12 hours at the office (a day),” said procurement manager Boontarika, speaking for herself and her equity trader husband. “How (would) we find time to care for our children?”

In another corner of Thailand’s corporate world, Anchalee Chaichanavijit, executive director of the Marketing Association of Thailand, thought about the same opportunity costs.

With the demands of her professional life weighing heavily, raising a child seemed a task that would demand additional energy, money, resources and time that Anchalee did not have.

“I don’t want to have children because … my own life is already tough enough,” she told the programme Insight, reflecting a sentiment increasingly common among many Thais.

According to a National Institute of Development Administration survey last September, 44 per cent of respondents expressed a lack of desire to have children.

The top reasons cited were child-rearing expenses, concerns about societal conditions’ impact on children and not wanting the burden of childcare.

These aversions are reflected in Thailand’s fertility rate, which stood at 1.08 last year, the second lowest in Southeast Asia after Singapore’s 0.97 last year.

Deputy Prime Minister Somsak Thepsutin warned that if the kingdom persisted on this trajectory, its population could be halved, from its current 66 million to 33 million, within 60 years.

While declining fertility rates are a global phenomenon, Thailand is set to face unprecedented challenges ahead.

HOW THAILAND IS AN ANOMALY

Thailand already stands out from its neighbours at similar levels of development. Countries such as Malaysia, the Philippines, Vietnam and Indonesia have fertility rates close to or hovering around the replacement level of 2.1 births per woman.

Ironically, what laid the foundations for Thailand’s economic growth could have precipitated its current problems.

WATCH: “Kids are too expensive!” How Thailand became one of the world’s fastest-ageing countries (47:07)

In 1970, Thailand launched its national family planning programme with the aim of moderating population growth and fostering economic progress.

By 1976, the programme had not only lowered the population growth rate to 2.55 per cent, but also exceeded its target of 26 per cent contraceptive acceptance. This success endures, with nearly three in four married women today practising contraception.

Tiffany Chen, a policy experimentation expert in the United Nations Development Programme’s Thailand Policy Lab suggested that the country’s outperformance could be linked to religion.

With up to 95 per cent of the population practising Buddhism, which allows certain forms of birth control, Thailand stands apart from neighbouring countries where religions that often prohibit contraception, such as Islam or Catholicism, hold sway.

Compared to some other nations, traditional attitudes about patriarchy have also changed in Thailand, said Sutthida Chuanwan, an associate professor at Mahidol University’s Institute for Population and Social Research.

Currently, Thai women outnumber men in the pursuit of higher education, and their labour force participation surpasses that of women in the Philippines, Malaysia and Indonesia.

“That actually limits the number of children that women tend to have, compared to those who might be housewives and just stay home,” said Kirida Bhaopichitr, research director for international economics and development policy at the Thailand Development Research Institute.

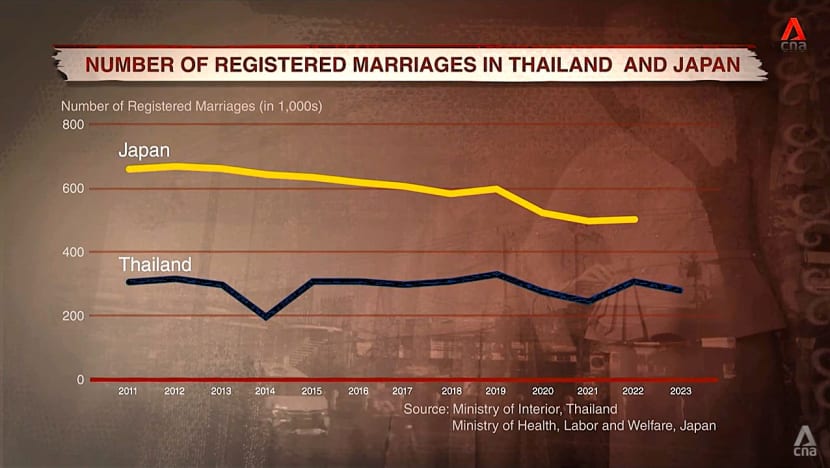

Economic pursuits do not, however, impede marriage prospects here, in contrast to countries such as Japan and South Korea, where declining marriage rates may contribute to dwindling birth rates.

Thailand has sustained a consistent level of marriages for over a decade, but married couples are simply choosing to stay child-free, either temporarily or permanently.

Nevertheless — again unlike Japan and South Korea — Thailand is considered a developing economy. This means it could be among the first nations to experience “getting old before (getting) rich”.

“When population ageing is gradual, it’s easier to adapt to the needs of an ageing society, whether it’d be in terms of healthcare, socio-economic infrastructure or the environment,” said Asean Centre for Active Ageing and Innovation interim executive director Sakarn Bunnag.

When change happens quickly, keeping up with it could be a struggle.”

THE PRICE OF PROGRESS

An ageing population signifies not only a decline in birth rates but also an increase in the elderly demographic. And in Thailand, seniors aged 60 and over constitute a fifth of the population already.

Thawatchai Potin in Bangkok is one of them. He has been repairing fans for a living since he was 25. At age 74 now, and 14 years past the retirement age, survival would be uncertain without work, he said.

“During COVID-19, for example, I had to share one egg with another person for a meal,” he shared. “If I go home (to Ubon Ratchathani province), I’ll be more like a burden to my children because I can still work.”

The National Economic and Social Development Council reported that 41.4 per cent of seniors had savings of less than 50,000 baht (S$1,840) in 2021, and 78.3 per cent earned less than 100,000 baht per year.

In comparison, around 4.3 million baht in savings is needed for retirement in the city.

To address this, the Thai government allocated almost 78 billion baht last year for the Old-Age Living Allowance, a monthly subsidy programme of up to 1,000 baht for senior citizens who are not pensioners or receiving welfare.

As the elderly population continues to rise, however, this initiative increasingly will put a strain on the government’s budget.

Projections indicate that Thailand could transition into a super-aged society, with those aged 60 and over constituting at least 28 per cent of the population, by 2033 or earlier.

This demographic shift will necessitate another slew of eldercare-related expenses, including for caregivers, quality medication and specialised nurses and physical therapists.

Adult children are starting to feel the pinch too. Providing care for their parents and themselves leaves little in the money pot for future offspring.

Although Thailand provides 12 years of free education at public schools, its central bank estimates that parents must still pay 1.6 million baht to support a child from kindergarten to university — more than six times the gross domestic product per capita.

Furthermore, even if a couple decide to have children, raising one is not easy in Thailand’s increasingly urban setting.

More than half of Thailand’s population resides in urban regions, notably the Bangkok Metropolitan Region, whose high population density has translated into challenges such as a high cost of living, social inequality, lack of green space, pollution and overcrowding.

“Given the current economic climate, unless the family is well off, both parents often must work. So a lot of people decide to put off having children,” said Bureau of Reproductive Health director Bunyarit Sukrat.

Despite this increasing focus on career and income among urbanites, Thailand’s labour force participation rate has declined since the last decade, highlighted Kirida.

A reduced pool of workers impacts productivity and income generation necessary for sustaining families and launching ventures in the country.

If left unaddressed, Thailand’s declining fertility rate could raise concerns among potential investors, possibly shifting their focus to other countries.

STRATEGIES FOR THE FUTURE

To diffuse the demographic time bomb, the Thai government has outlined three main strategies.

The first two strategies involve fostering an environment that promotes both childbearing and child-rearing as well as improving public attitudes towards family upbringing. “We aim to reduce the burden on parents as much as possible,” said Bunyarit.

This includes providing support such as designated breastfeeding areas, day-care facilities and financial assistance, ranging from subsidies on essential items to tax benefits for parents with multiple children.

Flexible working hours for women with young children is another area slated for improvement. In this regard, economist Piyachart Phiromswad emphasised the importance of private sector collaboration in developing policies to support working women in raising children.

The third strategy focuses on enhancing access to various reproductive health services.

The government plans to expand access to assisted reproductive technology for young singles who aspire to raise children. Furthermore, with the country set to legalise same-sex marriages, access to the same services may be extended to gay and lesbian couples.

As for the silver tsunami, projects such as the Chulalongkorn University Platform for Ageing Research Innovation help to promote healthy ageing with urban communities.

The platform’s efforts centre on enhancing socio-economic conditions, healthcare services, technology integration and the physical environment.

For instance, curated spaces such as a geriatric-friendly garden for the community in Sapsinmai facilitate social interaction among seniors whilst set in an environment tailored to their physical needs.

Chersery Home International Hospital chief executive officer Gengpong Tangaroonsanti also advocates a shift away from age-based categorisation to functional age assessment.

He proposes that age 60 be considered the new middle age and that retirement be based on functionality rather than age.

As traditional ideas about growth centred on labour and consumption also become increasingly irrelevant, what happens in one of the fastest-ageing developing countries could be a sign of things to come.

“The clock started (ticking) a long time ago,” Piyachart said. And Thailand’s future may depend on its ability to “transform these (demographic) challenges into opportunities”.

Watch this episode of Insight here. The programme airs on Thursdays at 9pm.