IN FOCUS: Record-low births, ageing society could halve Thailand's 66m population, but it's not a done deal yet

A population squeeze could have dire consequences for the workforce and productivity. While raising awareness is imperative, analysts say much also hinges on support from the government and private sector.

The birth rate in Thailand is plummeting, with 2022 recording the lowest number of births in more than seven decades. (Photo: CNA/Pichayada Promchertchoo)

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

BANGKOK: Having children is the last thing on Ms Phanphaka Haworth’s mind.

Besides potentially hindering her career, the 39-year-old university lecturer believes having kids would be a huge struggle in her home country Thailand, which she said offers limited support for modern-day parents and lacks environments conducive to raising a family.

“If I have to bring up a child in this country, I’d be so exhausted in so many ways. The government support isn’t good enough and the social condition isn’t that great. There are many issues such as living conditions and the air quality,” she told CNA.

“Should I have to raise my kid in Thailand, I wouldn’t want to have one.”

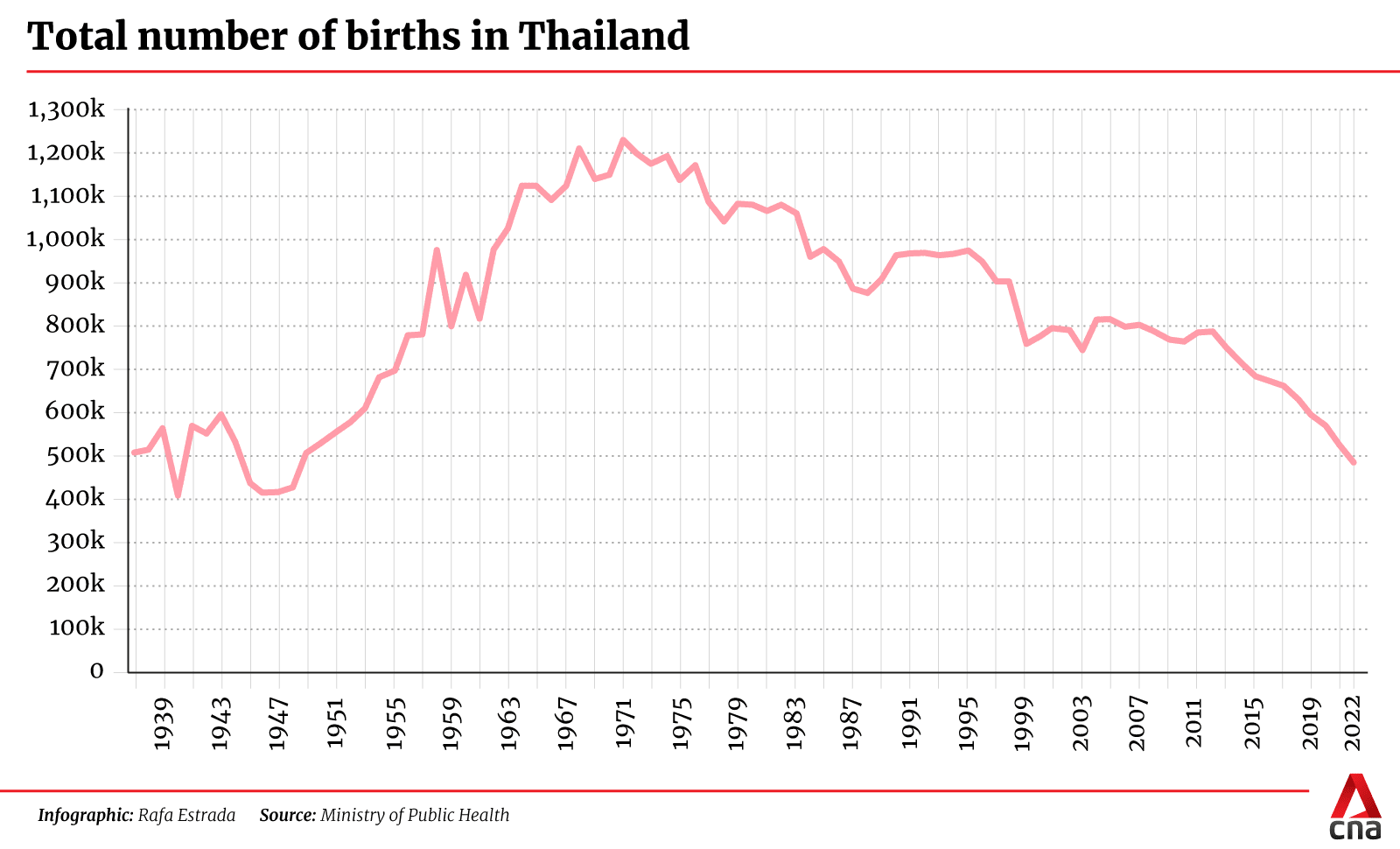

Ms Phanphaka is far from alone in her views, as the data makes clear. The number of births in the Southeast Asian nation plunged to a record 74-year low in 2022.

The demographic disruption is two-pronged - a greying society is taking deeper root as well, with the elderly already making up roughly a fifth of the kingdom’s people.

Other countries in Asia such as China, Japan, South Korea and Singapore are grappling with similar population trends.

But the projection is stark in Thailand.

If the kingdom continues in this direction, its population of 66 million will halve before the turn of the century, leading to profound impact on the economy, healthcare and development.

Experts say defusing the crisis or at least softening the blow hinges on raising awareness and changing mindsets, ramping up support by all sectors, and making sure the measures are introduced at pace as the clock ticks down.

“THAI PEOPLE WOULDN’T HAVE CHILDREN”

Arresting the declining birth rate is a long game that experts say requires meticulous planning, continuation and significant input from the state, the private sector and the public.

The current government of Prime Minister Srettha Thavisin is well aware of the population projection and its long-term implications for the labour force and productivity.

Upon taking office in September, Public Health Minister Dr Cholnan Srikaew stressed how vital procreation is for the country’s competitiveness and vowed to put the promotion of childbirth on the national agenda.

He underlined the need to change public perception of how having many children could make them poor.

“Thai people wouldn’t have children, especially those who have good education, knowledge and abilities and are financially equipped. They wouldn’t do it,” the minister told parliament on Sep 12.

“This is something distorted in Thai society,” he added.

On Dec 25, a committee set up by the Ministry of Public Health will hold a meeting with related units to discuss a comprehensive framework for the promotion of childbirth, safety of mothers and babies, and quality children.

The ministry also plans to open fertility clinics in every province and develop measures to reduce parenting burdens, aid women who have difficulty conceiving, and make assisted reproductive technology accessible for single and LGBTQ people.

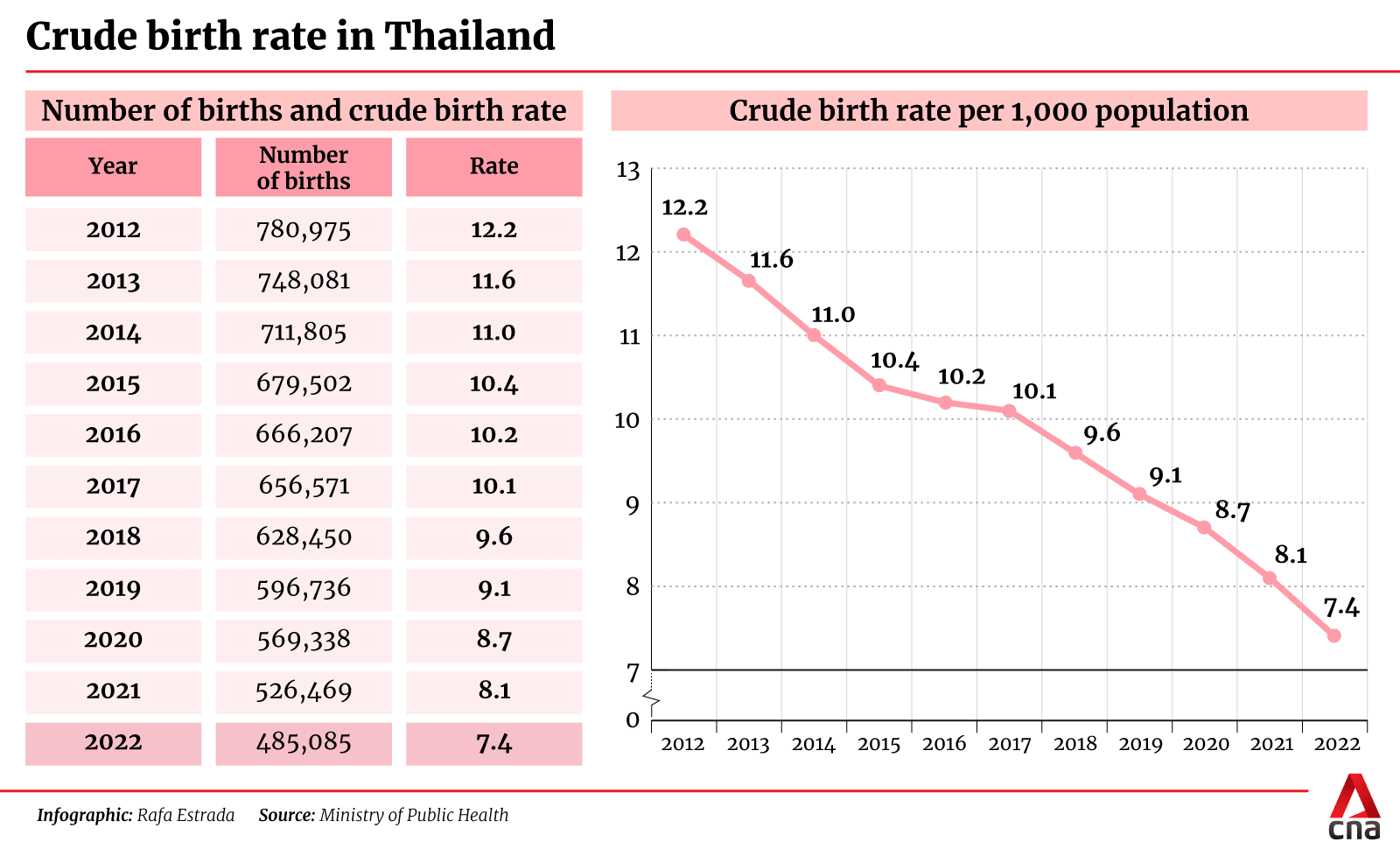

The move is a response to Thailand’s plummeting births, which dropped by nearly 40 per cent in just a decade – from 780,975 in 2012 to 485,085 in 2022.

According to the Health Department, the average number of children born to one woman of reproductive age fell to 1.08 last year.

The rate is substantially lower than the replacement level of 2.1 births per female, which would enable the country to maintain its population from one generation to the next.

“If the situation continues like this, where one family has around one child, our population will shrink by half in 60 years – from 66 million to about 33 million,” said Dr Piyachart Phiromswad from the Sasin Graduate Institute of Business Administration at Chulalongkorn University.

The economist has studied the impact of demographic transition in Thailand and discovered a “drastic and very rapid” change in the fertility rate over the past four decades. The decline was so significant in the last two years that deaths exceeded births in the country for the first time.

Besides the projected depopulation, Thailand’s workforce is also forecast to decrease from more than 40 million people at present to 14 million people by 2083.

“At the same time, the elderly population is estimated to grow from about eight million people to 18 million people – or around half of the country,” Dr Piyachart added.

SHIFTING MINDSETS AND INADEQUATE SUPPORT

Thailand has the second lowest fertility rate in Southeast Asia after Singapore, which recorded 1.04 births per woman in 2022.

Other neighbours such as Cambodia, Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines and Vietnam reported higher fertility numbers, either near or above the replacement level.

Analysts say the demographic shift in Thailand is a multidimensional issue that stems from different factors such as higher education, reduced inequality in gender roles and social values that increasingly prioritise career achievements.

Successful family planning policies and socio-economic conditions like social inequality, limited income and low-quality education have also discouraged people from having children.

Despite the government’s desire for more babies, raising a family is no easy task for ordinary Thais when the support system cannot catch up with rising living costs or demand for both parents to work.

The statutory maternity leave of 14 weeks – including weekends and public holidays – does not allow much time for working parents to nurture their infants. Even when they need to go back to work, analysts say childcare centres are inadequate and high-quality facilities are expensive.

“When the government asks people to have children for the country, we have to ask them back: What does the country give us in return?” said Ms Phanphaka.

Although the government provides various subsidies, she asserted they are not good enough and that parents are left with no choice but to work harder to provide a good standard education and a good life for their children.

“Thailand isn’t pleasant. It’s not the kind of society that’s good enough to make me want to have a child,” she told CNA.

MORE MONEY FOR PARENTS

To increase the population, experts say the government should be resolute and consistent in providing parents with comprehensive support that would make child-rearing less of a struggle.

Mr Siripong Kaimuk, a senior economist from the Bank of Thailand’s macroeconomic department, suggested the state should increase financial assistance to better reflect the cost of living and ease parent’s burdens in caring for a child, whether it would be in the form of a lump-sum grant for each newborn baby or subsidies on tuition fees and medical care.

Currently, a newborn baby whose family earns less than 100,000 baht (US$2,800) per annum is entitled to a monthly allowance of 600 baht from the Ministry of Social Development and Human Security until they are six years old.

A family with social security can also claim an 800 baht grant each month for six years after the birth of their child, on top of the childbirth allowance of 15,000 baht.

Still, the financial aid is too small compared with monthly costs for a child. A box of 3,800-grammes milk powder, for instance, is priced at 3,400 baht, while a set of 120 diapers costs about 1,400 baht.

While increasing financial support means higher government spending, analysts say it has demographic benefits and is achievable through efficient budget allocation and good management.

“There is no way to increase the population instantly. You can’t just give people money and expect them to have children. It requires various policies and integrating them,” Mr Siripong added.

BETTER CHILDCARE SERVICES

Besides monetary measures, childcare facilities are also key in improving the birth rate.

Dr Boonyarit Sukrat, director of the Reproductive Health Bureau, Ministry of Public Health, pointed out that the biggest problem for many parents is a lack of helping hands, partially because most childcare centres only take in children aged two and above.

“The problematic period comes after maternity leave, when the baby is about three to six months old,” he told CNA.

While raising the number of childcare facilities may seem like an obvious solution, Dr Boonyarit acknowledged it would require major investment for the construction and sourcing of qualified child carers.

Officials are trying to come up with effective solutions and one of them could be increasing the capacity of existing facilities to accommodate infants, he said.

By putting childbirth promotion on the national agenda, the Ministry of Public Health hopes to create an environment that is more conducive to bringing up children, where parents’ financial burdens are better subsidised and the infrastructure necessary for childcare is stronger and more accessible.

The Health Department has also proposed improving rights to childcare leave and increasing paid maternity leave to six months as well as introducing more flexible working hours or options to work from home.

“Various measures implemented by different countries may not be able to reverse the total fertility rate right away, but at least they should help slow down the fall,” Dr Boonyarit told CNA.

LOOMING THREAT TO THE WORKFORCE

While deciding whether to have children is a basic right, fewer newborns can have far-reaching consequences for labour-intensive economies such as Thailand.

Mr Siripong from the Bank of Thailand warns that low birth rates can trigger a chain reaction that not only squeezes the country’s workforce and productivity, but also lowers domestic consumption, foreign investments and government revenue from taxes used in development projects.

“Investors may not see Thailand as one of their first options and consider our neighbouring countries with higher working-age populations and consumption instead,” he explained.

At the same time, the country may need to rely more on imports in the future if its export sector takes a hit from the shrinking labour force, he added.

Apart from government initiatives, observers say input from the private sector is equally crucial for Thailand’s population management.

Dr Piyachart from Chulalongkorn University noted the impact of depopulation should be huge for big corporations that rely on labour and domestic consumers.

More companies should therefore provide an effective mechanism that would help workers maintain a healthy balance between work and family, he suggested.

“These organisations can take a leading role and work together to push for change. This would benefit them as well,” the economist said, adding the private sector still lacks sufficient awareness of the underlying problems and has yet to provide adequate incentive for employees to have children.

For the short term, analysts say Thailand may need to develop technologies to boost its productivity as well as bring in more foreign workers to maintain its labour force like Singapore, Japan and several Western countries.

As of October this year, there were 2.6 million foreign workers in the kingdom but only 6.5 per cent of them were skilled labour.

COPING WITH A “COMPLETE-AGED” SOCIETY

Running parallel with the plummeting birth rate is the rapid growth of Thailand’s elderly population.

The second largest economy in Southeast Asia is on the cusp of becoming a complete-aged society, where more than 20 per cent of its population are older than 60.

Data from the Department of Older Persons in June showed that the elderly made up 19.4 per cent of the total population.

This is only set to go up in the next 20 years as those who were born between 1963 and 1983 - when the country welcomed more than 1 million births per year - cross the age threshold.

It is a reflection of how people in Thailand are living longer lives. Still, growing older also comes with the associated health risks, pressuring healthcare and possibly requiring the government to spend more money.

But there could be a silver lining.

Many experts see seniors as an untapped resource that could boost the country’s workforce – especially when the working-age group is on course to decline due to the falling birth rate.

“A certain number of the elderly are still strong. As a result, we may need to provide them with more job opportunities so they can contribute to society and maintain productivity,” said Dr Phusit Prakongsai, secretary general of the Foundation of Thai Gerontology Research and Development institute (TGRI).

A change in perspective on the elderly and population ageing is an important step in unlocking their potential and utilising their experience and skills to strengthen Thailand’s labour force, he added.

What exactly is an ageing society?

It is where older persons make up a growing proportion of the population. There are three categories:

- Aged society: The population aged 60 years or older is more than 10% of the total (or the population aged 65 years or older is more than 7%).

- Complete-aged society: The population aged 60 years or older is more than 20% of the total (or the population aged 65 years or older is more than 14%).

- Super-aged society: The population aged 60 years or older is more than 28% of the total (or the population aged 65 years or older is more than 20%).

Source: Foundation of Thai Gerontology Research and Development Institute

“HIRE ME”: GIVE THE ELDERLY A CHANCE TO WORK

Thailand is home to about 13 million elderly people and according to Dr Phusit, the majority of them are poor.

In 2021, the Department of Older Persons reported that around 46 per cent of the elderly population did not have savings. Moreover, nearly half of those who did reported savings of less than 50,000 baht.

“A number of elderly people are also in debt. Some debts were incurred when they were still working. Others belong to their family members,” Dr Phusit told CNA.

Once removed from the workforce, life has become a constant struggle for many elderly people in Thailand. A number of them are homeless, especially in big cities such as Bangkok, where more than 1,200 people live on the streets.

Sixty-eight-year-old Wattana Noottarn was one of them. A few years ago, the former mechanic lost his job and started living on the pavement along Ratchadamnoen Avenue, sharing the space with hundreds of other homeless people.

“Everything had fallen apart. My life was a failure,” he said, adding a conflict with his family meant he could not go back home.

No matter how hard he tried, Mr Wattana could not find a stable job that would help him afford food or shelter.

There was no job for someone his age, not until he was approached by the Mirror Foundation, a non-governmental organisation that has advocated social development in Thailand since 1991.

Its Hire Me project – "Jangwan Ka" in Thai – seeks to provide jobs for people who cannot enter the employment system due to factors such as old age.

“Thailand hardly provides jobs for the elderly … they’re often perceived as having less ability to work,” said the Hire Me project manager, Mr Sittiphol Chuprajong.

“Actually, many of them still want to be employed because working isn’t just about earning income but also living their life, socialising and having friends,” he added.

Since 2020, Hire Me has attracted 160 participants and counting. Most of them are the elderly and about 20 per cent are people in their fifties who do not have enough funds to start a new life on their own.

Today, Mr Wattana earns 2,500 baht per week from working in the foundation’s warehouse. He can afford to pay 2,100 baht a month for a room, pay for his meals and buy a second-hand mobile phone to watch TikTok videos during his free time.

“It’s like my life was illuminated again after everything had gone dark. There is hope,” he said.

“I’m happy, very happy.”

SAVE UP FOR RETIREMENT

Thailand is facing considerable challenges as the elderly population shifts in the opposite direction to the birth rate.

Even should moves be made to return the elderly to the workforce, concerns remain over their financial security and health issues as well as how existing infrastructure can accommodate more seniors.

Ms Kingkan Ketsiri from the Bank of Thailand told CNA not much has been done to improve their welfare benefits and that the burden would fall on the working-age population in the future if nothing changes.

“Given that we have fewer newborn babies, we may not have enough people to take care of the elderly and that means more responsibilities for working-age individuals,” said Ms Kingkan, assistant director of the macroeconomic department.

As an aged society becomes even more of a reality in Thailand, analysts say further awareness about health, retirement planning and savings is needed.

Dr Phusit from TGRI advised that people should start doing it early, before they turn 60, in order to be self-dependent and avoid creating more burden for the government.

Additionally, related parties should look at how to better manage the healthcare system and offer social welfare services for the elderly with special needs in order to assist their families.

“Sometimes, the children or grandchildren of the elderly have to quit their jobs to look after them as they’re bed-ridden. So if we have a system that would help these families or communities with such patients or people with dementia, that would help improve the quality of life for Thais in general,” said Dr Phusit.

In Chonburi, Ms Phanphaka has already started saving up for her retirement. One of the plans is to find a good nursing home when she is old, and alone.

For her, spending her final years in a facility without children is hardly a concern.

“Just planning my retirement is already hard enough,” she told CNA.

“If I have a child and have to work for my child’s future as well as my own, it’d be exhausting.”