As both US, China de-risk, this is how India, Indonesia stand to gain

Can India replace China as a manufacturing powerhouse? Can Indonesia navigate the geopolitics by bringing in companies from the East and the West to work together? The programme When Titans Clash looks at the shape of things to come.

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

MUMBAI and JAKARTA: Last year, India had plenty to celebrate. Apple opened its first flagship store in the country and shifted a chunk of its manufacturing from China to India as well. And it was joined by many other companies.

United States-based Micron Technology agreed to build a US$2.75 billion (S$3.7 billion) semiconductor facility in Gujarat state, with Micron spending up to US$825 million and India funding the rest.

US-based Applied Materials announced it will build a collaborative engineering centre in Bengaluru, with an investment of US$400 million. Another semiconductor firm, Lam Research, will start a training programme for 60,000 Indian engineers.

Taiwan-based Foxconn, the world’s largest contract manufacturer of electronics, said it will double its workforce and investment in India by this year.

Related stories:

The sense that it is India’s time to shine comes as both the US and China de-risk by, for example, reducing excessive dependency on any one country.

De-risking is altering global supply chains, resulting in changes across several regions. One of them is India; another is Southeast Asia, such as in Indonesia, where rapid industrial changes are afoot.

“India is in this sweet spot at the moment, with the combination of geopolitics as well as domestic policies,” said Jivanta Schoettli, assistant professor in Indian politics and foreign policy at Dublin City University.

With de-risking underway across the world, the programme When Titans Clash looks at how the biggest economies in the subcontinent and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (Asean), respectively, stand to benefit.

WATCH: New economic world order? Industrial policies and de-risking from China (45:56)

WOOING INDIA

In India, the Apple story “perhaps took a lot of people by surprise”, according to Schoettli.

“There was quite a lot of scepticism in terms of … India actually (being) able to deliver the skills (that are) necessary, the talent, the land, the locations, the logistics,” she cited. “Somehow all this is being worked out.

“Now the projections are that Apple’s going to possibly get 15 per cent of its revenue (growth) and 20 per cent of its (user growth), I believe, (from India) over the next five years.”

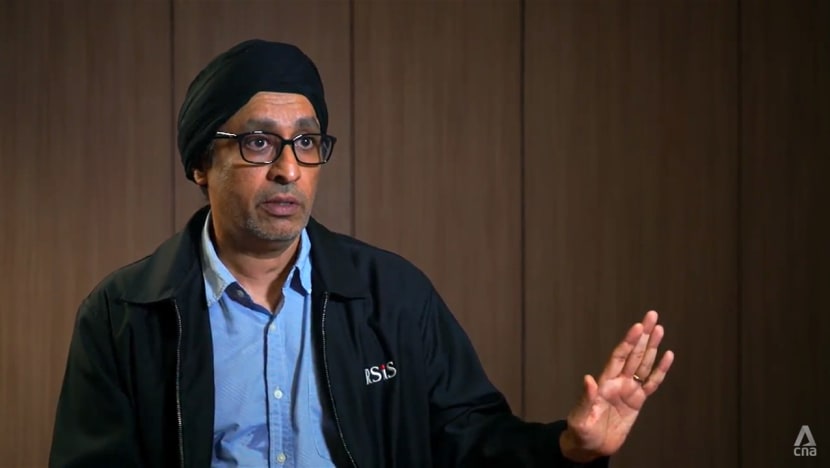

For a long time, job creation in India had been “a big problem”, said S Rajaratnam School of International Studies senior fellow Sinderpal Singh, the assistant director of the school’s Institute of Defence and Strategic Studies.

Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi launched the “Make in India” campaign in 2014, but only in the last two years did chief executives and governments start paying close attention.

“It’s very hard to ignore the geopolitical background,” said Singh. “India is coming of age. And there’s some sense that this is a zero-sum game — that what China’s losing, India’s gaining.”

Western countries are courting India even though Modi has not turned his back on Russia, with his country importing more Russian oil and bilateral trade accelerating as the Ukraine conflict continues.

At the White House, new partnerships between the US and India in defence, space exploration and semiconductor manufacturing were inked last year.

One of the agreements allowed the sale of American-made armed MQ-9B SeaGuardian drones to India and for US-based General Electric to partner with Hindustan Aeronautics to produce jet engines for Indian aircraft.

India also signed the Artemis Accords, a blueprint for space exploration co-operation among nations participating in American-led lunar exploration plans.

The US’ National Aeronautics and Space Administration and the Indian Space Research Organisation also agreed to make a joint mission to the International Space Station this year.

Amid the diplomatic engagements, including in France, there was little mention of India’s backsliding on religious and press freedoms. Under Modi’s government, religious hate crimes have increased, with several high-profile lynchings of Muslims.

“The American administration understands how important the relationship with India is at the strategic level,” said Singh. “Especially now with (President Joe) Biden, India is so important that they’ve been trying to stay clear of … some of these issues.”

Geopolitics is not the only factor, however, behind some of the recent corporate decisions. China has an ageing population, of which more than 30 per cent will be over 60 years old by 2035.

India, on the other hand, overtook China last year to become the world’s most populous nation, with just over half of its 1.4 billion people under the age of 30.

“It’s not just about producing for export, but it’s combined with the huge market potential, the huge attraction of an increasingly affluent middle class, or not necessarily affluent but a class that’s got some discretionary spending power,” said Schoettli.

BOTTLENECKS AND CHALLENGES

India does have bottlenecks but is now trying to resolve them by streamlining the implementation of infrastructure projects across the country.

The national highway network, for example, will be expanded along with railway capacity for transporting cargo as well as the electricity transmission network for easier access to electricity.

The infrastructure plan includes the creation of around 200 new airports, heliports and water aerodromes to boost aviation as well as 20 new mega food parks, 11 industrial corridors and two new defence corridors in Tamil Nadu and Uttar Pradesh.

Like many other countries, India is also offering subsidies and facilitating trade. It has set up a production-linked incentives scheme for sectors such as the manufacturing of solar photovoltaic modules and advanced batteries.

Related stories:

Even so, government ministries are “quite frank” about the current challenges, from the issues with reliability of electricity to logistical and regulatory issues, which foreign investors may be “well aware of”, cited Schoettli.

“If you decide to come to India and invest, you’ve probably come in with that preception … that (there) is going to be a lot of hurdles,” she said.

Hopefully, there’s an element of almost pleasant surprise that the government’s trying quite hard, I think, to overcome (them).”

For companies thinking of moving their supply chains from China to India, the challenges include a lack of skills. While India has cheaper, abundant labour, the quality of its workforce needs upgrading.

India continues to have high levels of poverty and malnutrition, with almost 12 per cent of its population living below the World Bank’s extreme poverty line. In China, that same poverty rate is nearly zero.

When it comes to tech talents, China reportedly graduates nearly twice as many science, technology, engineering and mathematics students compared to India. Beijing also invests significantly more in research and development and industries such as robotics, artificial intelligence and biotechnology.

For these reasons, Anthony Saich, the director of the Rajawali Foundation Institute for Asia and Daewoo professor of international affairs at the Harvard Kennedy School, thinks it is “very difficult” to shift industries out of China.

He cited Apple supplier Foxconn, which has about 200,000 workers at its plant in Zhengzhou, Henan province.

“Roads, bridges built by the Chinese government, dormitories set up by the Chinese government — it’s hard to think of another country that’d be able to provide that sort of infrastructure for a major company like that,” he said.

“(Apple) can’t really get out of China, no matter what the bigger politics (are). … Value chains, supply chains (are) integrated into a global model, so you can’t just snip that off and say, ‘… We’re off to India.’”

NICKEL MINING IN INDONESIA

For Southeast Asia, the open multilateral trading system has been highly beneficial.

In the 1980s, the region’s gross domestic product per capita was at the level of sub-Saharan Africa. Today, it is 3.5 times higher than sub-Saharan Africa, cited World Trade Organisation (WTO) research economist Victor Stolzenburg.

Southeast Asia’s been able to integrate with the whole world due to open trade policies and being positioned just ideally … on the map.”

But de-risking, in the form of supply chain diversification, has also brought in investment.

One of the region’s largest nickel production centres, if not the largest, is the Indonesia Morowali Industrial Park (IMIP) in Sulawesi. Here, the floodlights stay on throughout the night, and more than 40,000 workers operate the site round the clock.

The park covers nearly 4,000 hectares — it takes 45 minutes to drive from one end to the other — and has its own power plants, port area and even an airport.

Just 11 years ago, the land was dense rainforest and home to about 3,000 villagers. Chinese investment, led by stainless steel giant Tsingshan Holding Group, was critical to the transformation of forest into factories.

Nickel exporter Hamid Mina was supplying the ore to China when his company, in partnership with Tsingshan, started building the first nickel processing plant in 2013.

“Tsingshan said, ‘We’re good (at) building the factory and producing. This is our know-how. You’re Indonesian, you know Indonesian rules, regulations, everything.’ So we split our jobs,” recalled Hamid, now IMIP’s managing director. “They have the technology, so we co-operate.”

Nickel, which has long been used for making stainless steel, is becoming an increasingly key component for lithium-ion batteries in electric vehicles.

The International Energy Agency estimates that by 2040, clean energy technologies will account for up to 70 per cent of total nickel demand.

Indonesia holds the world’s largest nickel deposits and is the largest nickel miner, extracting almost half of the global supply. China, meanwhile, has some of the world’s largest battery and green tech companies.

At its core then, IMIP exists to smelt and refine nickel on a massive scale. And it contributes to China’s efforts to diversify its sources of critical inputs that fuel its economic growth.

ELECTRIC VEHICLE AMBITIONS

Global growth in the electric vehicle (EV) and battery industries is not, however, the only driving force behind Morowali’s growth.

There is Indonesia’s ban on nickel ore exports since 2020, a move the EU, the WTO and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) have criticised.

But the ban compelled foreign investors to build smelters in the country, adding value to its metal exports and creating jobs. In 2014, Indonesia’s nickel ore exports were worth US$1.1 billion; in 2022, it exported US$34 billion in nickel products.

“You see, the multiplier is very huge,” said Septian Hario Seto, a deputy minister in the Co-ordinating Ministry for Maritime and Investment Affairs.

Today, various companies are working together in Morowali to produce this 21st-century gold — with almost US$5 billion to US$6 billion of investment “now coming in every year”, said Hamid.

“We welcome everybody,” he added. “We don’t care (whether) you’re from the West or from the East. We’re for the business. No politics.”

To move further up the value chain, Indonesia is creating an “ecosystem” for EVs and lithium batteries, said Septian.

In 2022, President Joko Widodo (Jokowi) launched the first EV assembled in Indonesia, made by Hyundai. The company is working with another two South Korean companies to make EV batteries in Indonesia.

Last year, when Jokowi visited Australia, the two countries signed deals in mining lithium and nickel to produce EV batteries as he highlighted strategic co-operation between the two countries in this field as a priority.

WATCH: Does world’s largest nickel miner need to choose between China and US? (8:34)

Setting up shop now in Indonesia is BYD, which joins fellow Chinese EV maker Wuling, while US company Tesla continues its investment discussion with the Indonesian government.

In the foreseeable future, nickel could be processed in Indonesia by Chinese companies, then assembled into EV batteries by South Korean and, potentially, Australian firms there, for cars made in Indonesia by American and Chinese manufacturers.

In a world grappling with geopolitical tensions, Jakarta sees such global partnerships as the way forward.

“We should avoid a concentration of the supply chain (in the hands of) one single party. But I think in an effort to diversify the supply chain, … we can’t just say, ‘Oh, I don’t want China,’” said Septian.

“Western countries would be 10 to 15 years behind … Chinese technology in terms of the nickel processing, so we can’t exclude.

“We can have co-operation that’s beneficial and mutual for every party, because … no single country, even no single region, can fulfil all the critical minerals that we need for this energy transition.”

For Southeast Asia, the outlook “remains very positive” because the region “continues to be critical to the multilateral trading system as we have it”, said Stolzenburg.

The IMF recently estimated that Asean “will continue to outgrow the world average by a factor of 1.5”. In trade, the region outgrew the global average in 2022, for example, by a factor of five.

“The starting point … is very positive,” said Stolzenburg. “Of course, there are downside risks. So far, it seems that Asean countries … are managing this well.”

He made it clear, however, that the positive outlook depends on this factor: that Asean is not forced to choose sides.

Watch this episode of When Titans Clash here.