This 26-year-old was conceived with donor sperm. She is grateful for it

Many sperm donors in Denmark are university students. One reason they come forward is to help others, one sperm bank has found. It opens its doors for the new documentary, The Baby Makers, in a broader look at the future of fertility.

Emma Groenbaek even works at the sperm bank her parents had gone to in their country, Denmark.

AARHUS, Denmark: There is someone whom Emma Groenbaek and her parents are grateful to although they have never met. This stranger helped them become a family 26 years ago.

He is the sperm donor who enabled Emma’s parents to have her.

Henning and Ida Groenbaek had tried for six years to have a child. After discovering that Henning had a low sperm count, they began, in Ida’s words, an “odyssey of different fertility treatments”, including unsuccessful rounds of in vitro fertilisation using his sperm and a donor’s sperm.

They were close to adopting a child when Ida got pregnant by donor sperm.

“All of us in the family … (are) very appreciative of what he’s done to help us,” said Emma in an Instagram Live session.

Emma is even working at the sperm bank her parents had gone to in their country, Denmark.

Cryos International started in 1987 and says it has the world’s largest selection of sperm and egg donors — more than 1,000 of them.

It has exported to over 100 countries including Cambodia, Sri Lanka and in Europe, and its customers who “can’t get children of their own” include heterosexual couples, singles and lesbians, its chief executive, Helle Myrthue, said in the two-part CNA documentary, The Baby Makers.

Infertility is a growing issue worldwide as birth rates in many developed countries decline and more couples struggle to have children. It is intertwined with societal shifts such as more single-mindedness about career and other life goals, and the postponement of parenthood.

WATCH: The race for babies — our fertility issues (46:06)

The Baby Makers travelled to countries such as South Korea, which has the world’s lowest fertility rate of 0.81, and to Israel, the most fertile of Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development countries, with a fertility rate of 2.9.

Whether in Asia or beyond, fertility has become a lucrative industry and a field in which researchers, doctors and entrepreneurs are pushing for scientific breakthroughs and new products and services.

In Denmark, the fertility rate is about 1.7, and some eight to 10 per cent of babies are born after assisted reproductive treatment.

The Nordic country also draws fertility patients from abroad. This is due to “more liberal legislation” for egg and sperm donation as well as its healthcare providers’ wealth of experience, said fertility doctor Bjorn Bay, co-owner of Maigaard Fertility Clinic.

For example, women do not have to be married or heterosexual to access fertility treatment. And they can keep trying at private clinics until the age of 46, a higher threshold than in some other countries.

SPERM BANKING IS SERIOUS BUSINESS

Denmark’s openness also means “it’s not shameful” to be a sperm donor, said Myrthue.

When she first started working at Cryos in 2018, people may have been “all giggling” and asking what she was doing in sperm banking, but it is a “very serious” business, with proper controls in place, she said.

One of the misperceptions of the sperm bank is that “a man can just walk in from the street and become a donor”, said Cryos scientific director and clinical geneticist Anne-Bine Skytte. “That’s not the case.”

WATCH: Inside the world’s largest sperm bank, in a Denmark university town (6:09)

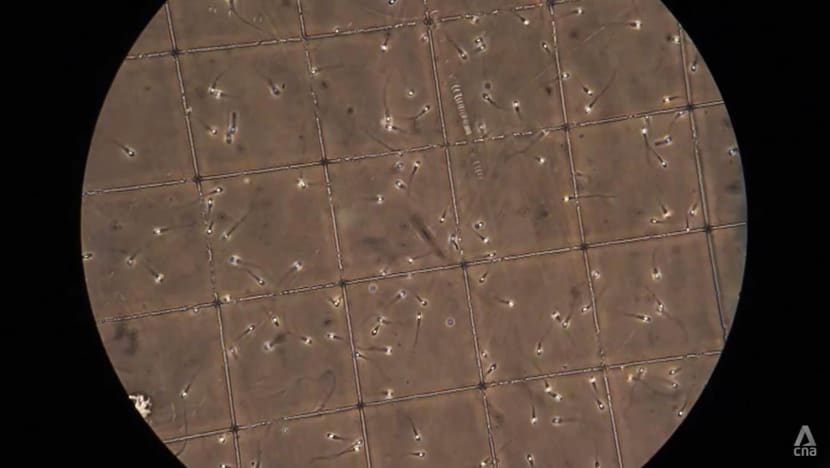

The process of accepting a donor takes, on average, three months — with information to be obtained and tests to be done to ensure, for example, the quality of the sperm.

“Good sperm should be swimming straight ahead. It shouldn’t go round in circles. It shouldn’t lie still. It should have one tail, not two,” said Skytte.

If the sperm does not look as it should, the donor would be asked to come in a second time.

“It may be that he’d been in a sauna, or he’d been having a fever,” said Skytte. “If he comes in again, a few weeks later, it may be all normalised.”

If the second sample is “still not okay”, he is not taken on as a donor. Instead, the sperm bank would ask him in for a third evaluation “as a service”, so that he may be referred to a doctor if this sample also does not pass muster.

The process is a “collaboration” between the donor and the bank, said Skytte.

Cryos looks at the potential donor’s family tree (three generations) to see if there is an elevated risk of diseases, such as colon cancer or dementia.

Donors cannot be people who travel a lot as they may pick up diseases from other countries. The bank also asks about their sexual behaviour as they cannot be at elevated risk of contracting sexually transmitted diseases, Skytte added.

Many of the sperm donors are university students, and Cryos is present in Denmark’s four university cities.

While they receive 200 to 500 Danish kroner (S$37 to S$93) for each donation, the company has found that many of them donate “because they want to help other people”, said Myrthue. Half of its donors are also blood donors, she noted.

Those who are selected have the option of ID and non-ID donation, unlike in some countries where there is no choice, she said. ID donations mean the donor child may, once he or she is 18, contact the sperm bank for the donor’s identity.

A non-ID donation means the child cannot get information on the donor. But either option allows clients to filter donors by certain traits, such as height, hair colour and eye colour, cited Myrthue.

The cost of donor sperm depends on multiple factors, such as sperm motility (ability to move efficiently), donor type and how much donor information the clients want.

Nowadays, there is the added boost from technology.

For example, Cryos staff used to look at sperm using a microscope and do a manual count; but there is now a computer-assisted method, which makes for more accurate and reproducible results, cited Skytte.

And instead of traditional pornography, Cryos now provides virtual reality (VR) goggles to donors. This, too, is evidence-based: The company has studied the effect of using VR and is due to publish its findings, said Skytte.

“If you compare this quality of sperm from a man masturbating (with) a man having sexual intercourse, the sperm quality is better when it’s stimulated by sexual intercourse,” she said.

“So, (by) making it as lively as possible, we may be able to improve the quality.”

Sperm supply took a hit, however, during the COVID-19 pandemic. Even after the initial lockdown, Cryos did not accept donations when it was not yet known if the virus could also be in sperm, said Myrthue.

The company is now rebuilding its stock, she added. “We just have to get the machinery up and running again.”

She believes that if more countries allowed sperm and egg donation, it would help “so many women” who would no longer need to travel to countries where the practice is allowed.

The company’s own egg banks are in the United States and Cyprus because commercial egg banks are not allowed to operate in Denmark, she cited.

In Singapore, sperm and egg donation are allowed with many rules in place — for starters, the arrangement cannot be commercial.

A ‘VERY WANTED’ CHILD

Even amid new developments in assisted reproduction, infertility remains a difficult topic to talk about openly.

Emma said a reason she started sharing her story online was that she found “everything surrounding donor conception was so negative”. She said: “I wanted to create a more diverse picture of what donor conception could be like.”

Her parents never hid the fact that she was donor-conceived, despite worrying that she would not understand their actions.

They made a children’s book telling a “very simple story” about how they needed help with having a baby and received it from a “nice man”, said Ida. From the time Emma was about three years old, they read it to her as a bedtime story.

Henning said he and his wife decided from the beginning that they could not “live a lie” and risk Emma finding out the truth “at a difficult age, like (as) a teenager”.

Such openness meant a lot to Emma. “It’s made me feel very secure in myself and in my family, because I felt like I was a very, very wanted child,” she said.

As Henning said in one of her Instagram Live question-and-answer sessions, “even though she’s not my biological daughter, she’s my daughter”.

She has younger twin sisters who were conceived by a process called intracytoplasmic sperm injection, whereby sperm is injected directly into the centre of an egg.

The method became established in Denmark about two years after Emma was born, and her parents opted for it “so I could also become a biological father”, said Henning.

While others may find it hard to understand what people grappling with infertility go through, he believes “being open makes it easier for yourself and … your friends and family”.

Emma is often approached for advice by people using donors, people looking to become donors as well as those looking to tell their donor-conceived children the truth. Her approach is similar to her father’s.

WATCH: The future of baby making (46:16)

“I do have an anonymous donor. It’s not been a problem for me, but it can be for some people,” she said.

“Honesty, and (being told the truth) from a very young age so that it’s … a natural part of your life, is the most important thing. And that’s what I try to communicate to people.”