How did conservative India come to repeal S377’s ban on consensual gay sex?

The decision to decriminalise homosexuality was not only greeted with relief by the LGBT community, it also found resonance in Indian society. The programme Insight finds out why and what’s next for activists.

There was an overwhelming response from gay rights activists and the LGBT community to the Supreme Court's ruling.

INDIA: Some have hailed it as a step towards freedom from discrimination, humiliation and oppression.

Certainly, India’s Supreme Court ruling on Section 377 (S377) of the Penal Code has given a new lease of life to millions who had been living under the weight of criminality and in the shadow of fear.

READ: India's Supreme Court ends colonial-era ban on gay sex

Not only was there an overwhelming response from gay rights activists and the lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) community, there was also support from the main political parties, like the opposition Congress party.

The ruling Bharatiya Janata Party did not oppose the judgment, while the Hindu group Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) even supported the ruling, saying that gay sex was not a crime but a moral issue.

While S377, which criminalises sexual activities "against the order of nature", remains in force in relation to sex with minors and bestiality, the court ruled last month that its application to consensual homosexual sex between adults was unconstitutional.

So how did its decision find resonance in a diverse but largely conservative society like India, with its mix of religions and cultures?

One factor is the country’s record on gay issues, in which centuries of tolerance before its British colonial rulers introduced S377 in the 19th century were followed by decades of bullying.

But that complicated past raises another question: Will the ruling really change social attitudes, remove stigma and grant LGBT Indians greater protection?

As experts and activists tell the programme Insight, it may take a long time for the community to be accepted as equal members of the world’s largest democracy. (Watch the full episode here.)

WATCH: What a rape survivor, lawyers and activist say (8:29)

EVOLVING SOCIETY

A chapter in Indian history may have been closed, but conservative figures and hard-line groups have vowed to fight a ruling they see as shameful.

“You can’t change the mindset of the society by using the hammer of law. This is against the … religious values of this country,” said Mr Ajay Gautam, the chief of the right-wing Hum Hindu group.

And yet Hinduism has been permissive towards same-sex love, with old temples such as those in the Khajuraho world heritage site depicting erotic encounters on their walls, pointed out Institute of South Asian Studies visiting senior research fellow Ronojoy Sen.

“Hindu society, both in ancient and medieval India, was much freer and more open,” said Dr Sen, who also cited characters who defy gender boundaries in the Mahabharata, the Hindu epic.

“With the coming of the British as well as reform movements of the 19th century within Hinduism, there was a certain closing of the doors and the minds, a certain sense of Victorian morality that came to the foreground … The more flexible aspects of Hinduism often fell by the wayside.”

In recent years, however, Indian society has been evolving. Data from 2006 showed that 64 per cent of Indians believed that homosexuality is never justified, and 41 per cent would not want a homosexual neighbour.

But a World Bank report in 2014 found that “negative attitudes have diminished over time”. In 2011, for example, a “third gender” category was added to the male and female options on India’s census forms for the first time.

Over 490,000 transgender individuals of all ages chose that option, although many observers believe that the figure is an underestimation, given the stigma attached.

And in 2014, the Supreme Court recognised transgenders as equal citizens under this rubric of the third gender.

A year earlier, the same apex court had ruled that S377 did not suffer from the “vice of unconstitutionality”, only to reverse its stand within five years following another petition.

A MATTER OF RIGHTS, NOT MAJORITARIANISM

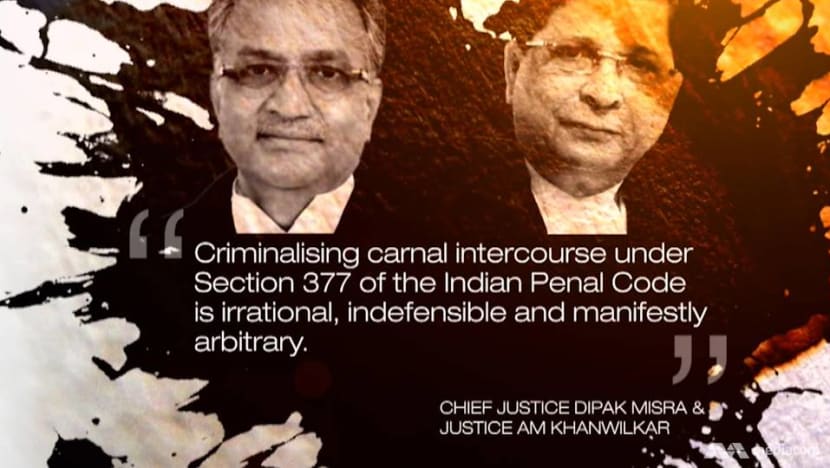

In delivering the unanimous verdict on Sept 6, Chief Justice Dipak Misra said: “Criminalising carnal intercourse under Section 377 (of the) Indian Penal Code is irrational, indefensible and manifestly arbitrary.”

Justice R F Nariman, another of the five Supreme Court judges on the bench, added: “Homosexuals have a right to live with dignity. They must be able to live without stigma.”

It was a “beautiful judgment”, said Ms Menaka Guruswamy, one of the petitioners’ lawyers. “(The justices) are saying that India … must be governed by constitutional morality, not majoritarianism, not popular morality, not social morality, but the Constitution's morality,” she said.

“That’s really heartening because, here, the Supreme Court is connecting it to larger issues of democracy … and just so much more than a simple reading of consensual sexual acts.”

Ms Katju agreed that the judgment will have a “far-reaching impact” because it “stresses the role of the court as a counter-majoritarian institution … to protect minorities against the will of majorities”.

To the lead lawyer in the case, Mr Anand Grover, the judgment affirmed India’s constitutional values – “that we need an inclusive society (where) each individual has … justice, social, economic and political (rights), liberty, equality (and) fraternity”.

“The majority can’t dictate to the minority. Even if that person is one individual, that individual’s rights would be upheld,” he said.

The court also acknowledged the 17-year legal battle the activists fought, which began in 2001 when the LGBT rights group Naz Foundation filed a public interest litigation in the Delhi High Court to challenge the constitutionality of S377.

Justice Indu Malhotra said: “History owes an apology to members of the community for the delay in ensuring their rights.”

That acknowledgement was what struck the group’s founder Anjali Gopalan because it was “unheard of in our system”.

While she found the political response to be muted in contrast to what the court said, the lawyer Ms Katju thinks political parties are “very clear” about where India is going, with half its population under the age of 25.

“The Indian voter is now, by and large, a young voter. And Indian voters are looking for India to play a role on the global stage. That includes taking a leadership position when it comes to rights,” she said.

S377’S OPPRESSION

For the LGBT community, however, S377 was not only a denial of rights, but also a veil of darkness that had enveloped their lives.

One such person who had to bear his pain in silence is Mr Manoj. Barely out of his teens, he was gang-raped multiple times but was afraid to report the matter for fear of being charged.

He was not the only one. According to Mr Grover, many gay men were victims of blackmail, violent assaults and rape by dating partners, the police and “even family members who wanted to convert gay men into straight men”.

The reason nobody could go (to a police station) was if they went there, they’d be identified as gay … So 377 allowed the violence to go on, and no remedies were available.

“Consent was immaterial, so a victim could be said to be also part of the sexual offence under 377," he added. "You’d have had to prove (non-consent).”

In Mr Manoj’s case, his assailants were three Delhi policemen. And they kept calling his number, telling him to meet them at lonely spots and threatening to book him under S377 if he refused. He attempted suicide three times.

The gang rape, blackmail and torture went on for one and a half years, until he managed to get their home numbers and threatened to call their wives and parents.

Another gay victim who was tortured was Mr Arif Jafar, when he was arrested in 2001 under S377 and thrown in jail for 47 days. He was not even given water and was forced to survive on sewage water.

The LGBT rights activist – who set up India’s first gay group, in Lucknow city, when he was 19 – had launched a programme to help HIV patients living in slums when the harassment and threats began.

But he never anticipated the nightmare that was to come in prison, where he was beaten and lost most of his teeth because of the unhygienic conditions.

After he was released on bail, he spent months in hospital fighting for his life. And even now, the police have not produced any evidence against the 48-year-old, who was one of the S377 petitioners.

He was held illegally in prison, noted Mr Danish Sheikh, an assistant professor and associate director of the Centre for Health, Law Ethics and Technology at the Jindal Global Law School.

So one of the things Mr Sheikh hopes can now change is that the law will no longer be misused as an “indirect way to persecute individuals”, and that male or transgender survivors of sexual assault can have judicial remedy.

LONG ROAD AHEAD

Though that part of the Penal Code has now been declared illegal, there is still a question mark over whether the LGBT community can find its place in India.

Gay rights activist and Hindustan Times writer Dhrubo Jyoti believes it is time to ensure and affirm non-discrimination in matters such as jobs, education and health care, which “the rest of the population can take for granted”.

These are “far more important”, he said, than what has happened in the West, where marriage, adoption and inheritance “became the next big focal points” after decriminalisation while everyday rights “remained on the back burner.”

Nonetheless, the issue of marriage will come up “soon”, predicted Mr Grover. “If an Indian citizen is married to (another) Indian citizen abroad, where the marriage is legal, and they come here … can (they) assert that the marriage is legal?”

In his view, it would be difficult for the courts to not recognise the marriage. “There are lots of issues that would open up now … like (intersex) athletes,” he added.

“Those people will now be coming into the fold of public life, where they’ll be demanding their place in the sun, as it were. And we’ll have to get used to it, in schools … institutions (and the) judiciary.”

One thing multimillionaire hotelier Keshav Suri hopes for is that LGBT couples will not have to “live in that fear that if one of us falls sick in India, the other one won’t be allowed to see (his or her partner)”.

Mr Suri, who got married in Paris, acknowledged that he could go to a private hospital where his husband could visit him, but that most Indians were not in that “privileged position”.

“How do you explain to a doctor that the family has disowned this person and (you’re) the only person there?” he asked.

The only way to advance LGBT rights, Dr Sen added, would be to go before the court again. “And even the courts might be reluctant to push it any further in the absence of a political will.”

Wherever the LGBT movement goes from here, people like Mr Manoj hope that they can be seen as ordinary members of society and that homosexuality is recognised as a variant of sexuality rather than a mental illness as some believe.

“We live in society, we’re from the society. We need acceptance from society as well. So we need to work on it,” he said. “It won’t be a one-day journey.”

Watch the episode here. The programme Insight is telecast on Thursdays at 8pm.

.JPG?itok=97AHNnkd)

.JPG?h=7721c754&itok=cUe3Ld2h)