How Starbucks’ growth nearly destroyed the business, until one man saved its skin

It cannibalised its own stores and lost its soul along the way, forcing its former CEO to return and steer it through a crisis. Inside the Storm looks at how he made his mark on this coffee giant twice.

Over-expansion was the start of Starbucks' woes.

SEATTLE: Starting off from a hole in the wall that used to be a junk shop, this roastery has turned the humble coffee bean into a US$22 billion (S$30 billion) empire, with almost 29,000 outlets worldwide.

It is hard to imagine that in 1971, and well into the 1980s, Starbucks only sold roasted coffee beans and equipment – it did not brew coffee to sell.

Today, this powerhouse from Seattle has taken coffee culture global, turning Italian terms like grande (large) and venti (twenty, for 20 ounces) into household words.

However, the world’s biggest coffee company once faced market saturation, brand fatigue and a struggle to stay relevant.

“People didn’t feel special going to a Starbucks any more. Saturation, increased competition, loss of touch with the consumer and automated machines made it feel less special as well,” said Singapore Management University assistant professor of strategic management Anne-Valerie Ohlsson-Corboz.

The story of how this coffee-house behemoth conquered the world but lost its way – to the brink of collapse – until one man returned to save its skin is told in Inside the Storm, a series about how major companies adapt in times of crisis.

IT STARTED WITH CAFFE LATTE

Starbucks’ founders – hipsters Gordon Bowker, Zev Siegl and Jerry Baldwin – were obsessed with coffee and had named their company after a character from Moby Dick: First mate Starbuck. And a twin-tailed mermaid became the image of their company.

But it was their marketing director Howard Schultz, appointed in 1982, who had big ambitions for the company. And in 1987, he bought out the three founders and gained control of Starbucks.

“The other founders … wanted to remain a roaster. They wanted to remain in a ‘we sell high-end coffee to discerning consumers’ and not ‘we’re going to make coffee’,” said Asst Prof Ohlsson-Corboz.

Mr Schultz’s direction for the future was inspired by a trip to Milan, Italy in 1983. “I was captured emotionally by the Italian coffee bar, the sense of community, the third place between home and work,” he has said before.

“I raced back to America and thought ‘this is what I want to do’ – transform the American coffee experience.”

He introduced the term "caffe latte" into the American vocabulary for the first time – a drink that was different from anything coffee lovers were used to.

It was a time when good-quality coffee was scarce, except in “very few bespoke types of operations”, said National University of Singapore Business School marketing professor Jochen Wirtz.

“(Starbucks) brought something very European to the United States market,” he added. “There was no competition. It was new, it was exciting. It took the world by storm, it took America by storm.”

The irony now is that it took until this September before the company could open its first branch in coffee-mad Italy.

READ: Starbucks' Italian dream comes true, but it is not cheap

READ: Starbucks pulls in crowds at first Italian cafe

‘INDULGENT ACT OF SELF-LOVE’

It was not just coffee with catchy names, however, that captivated consumers. There were also friendly baristas and the craftsmanship behind each cup.

“People stopping at a Starbucks on their way to work was almost like an indulgent act of self-love. They’d go in and buy themselves this relatively expensive coffee, and they’d feel like they’d treated themselves,” said Asst Prof Ohlsson-Corboz.

The vision of Starbucks as a “third place” – a cosy environment where people could gather and connect – was a success.

That idea also became ingrained in American culture, with characters from the comedy series Friends making it cool to while away the hours in the local coffee house.

The world began to socialise, gossip and strike business deals in the armchairs of Starbucks. And they also spoke the language.

“It was a sense that you and I are part of the same club because we both know what a venti is,” said Asst Prof Ohlsson-Corboz.

“The cappuccino, even the Americano and the latte – all these words that we now refer to as if they’re completely natural in our coffee terminology. (Starbucks) created a vocabulary that brought people together. It was a brilliant move.”

And the company made sky-high profits. It was making about US$0.50 cents profit on a US$3 latte. But with supersized drinks, such as a large latte with extra toppings, its profit margin almost tripled to around US$1.40 per cup.

KILLING THE ROMANCE

In 2000, Mr Schultz announced record sales of over US$2 billion. But that year, he decided to step down as chief executive officer and take a hands-off attitude in the boardroom.

His heart was no longer in it, and he needed a new challenge. He left the company in a strong financial position, but under the new management, Starbuck’s strategy changed.

Over the next decade, it embarked on a quest for expansion that stretched the brand to breaking point.

Its original value proposition – consumers sitting in the cafe and enjoying their coffee – was set aside.

“Real estate is expensive. I make a lot more money if you buy in and take away,” said Prof Wirtz. “(But) push too much on takeaway, again, what’s left of the Starbucks experience?”

Starbucks also ditched the traditional coffee machine and went fully automatic.

Former Starbucks barista Suhaimie Sukiman said: “That kind of kills the romance … about the art of making coffee. It becomes almost like a fast food business, and I personally felt as if it lost the charm a little bit.”

The company expanded its product offerings, going into hot food, compact discs and film sponsorship.

In 2007, its stock price plummeted by almost 50 per cent as the market reacted to the weakening brand and the beginning of a global recession.

RETURN OF THE COFFEE KING

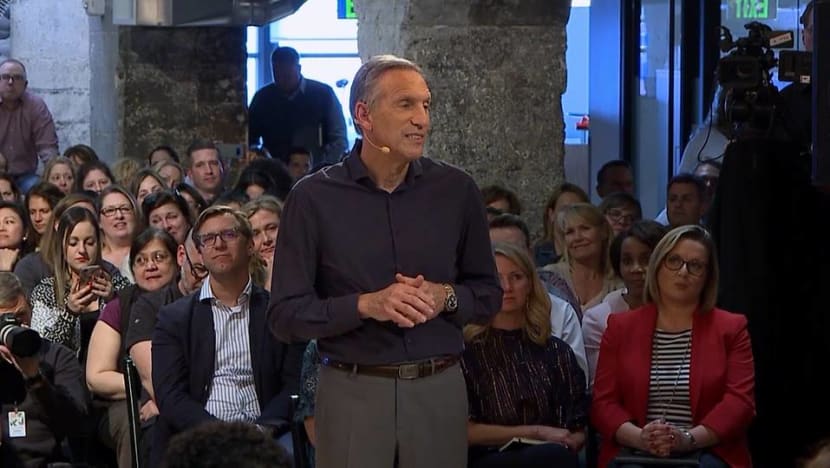

With the company facing a crisis, Mr Schultz returned in 2008. “We were drifting a bit towards mediocrity and kind of losing our voice. I needed to come back,” he said.

I didn’t want to be a critic on the sidelines. If I was going to be critical and concerned, I had to get back in the game.

One of the first things he did, in February 2008, was to close Starbucks’ 7,100 stores across the US for more than three hours so that its baristas could be re-taught the art of brewing coffee.

It lost about US$6 million in sales, but he was banking on the brand credibility it could restore to be far more valuable.

He also needed to address the size of the company, which had ballooned to over 16,000 stores worldwide.

That same year, he closed 600 stores in the US alone, of which 70 per cent had been open for less than three years.

While this made more than 12,000 employees redundant – the most in its history – the economic climate had changed by late 2008, and the stores had become a drain on profits.

“The new shops … had lower revenue per square foot than the earlier shops. New shops started to cannibalise existing shops. Suddenly, the growth was gone,” said Prof Wirtz.

So Mr Schultz re-energised the brand, one cup at a time and focusing on the customer experience by, for example, ensuring that its warm breakfast sandwiches no longer overpowered the coffee aroma, as well as cutting down its product offerings.

“We’d convinced ourselves that a new flavour of frappuccino was innovation. That wasn’t innovation,” he said.

WATCH: How one man saved the Starbucks empire (5:12)

CHINA AND BEYOND

After stabilising the brand, Mr Schultz eyed further growth, and the company has since shown no signs of slowing up. But besides Italy, there was another territory left to conquer: China, one of the world’s fastest-growing markets for coffee drinkers.

This year, Starbucks partnered with internet giant Alibaba in a delivery tie-up as part of its strategy to adapt to local needs.

Employing a more culturally sensitive approach than before, Starbucks has 3,400 stores in China now and plans to expand that number to 6,000 stores by 2022. In Asia, it has also started tailoring new types of drinks for local preferences.

But in June, Starbucks lost a piece of its DNA for a second time: Mr Schultz announced that he was stepping down as executive chairman, having already resigned as CEO last year.

Despite the uncertainty caused by his departure, the company’s fiscal fourth quarter earnings hit a record of US$6.3 billion, up 10.6 per cent from US$5.7 billion during the same period last year.

Under new CEO Kevin Johnson, the company is aiming to increase the number of stores worldwide to 37,000 by 2021.

But the challenge is to manage this 28 per cent growth from its current level while preserving the heart of the company.

Author John Simmons, who interviewed Mr Schultz for the book The Starbucks Story, said: “Businesses go out of business – it’s part of the natural cycle of things.

“Starbucks isn't immune from that. What it needs to do is what every surviving brand needs to do. It needs to remain true to its core principles and to the essence of its brand for as long as that’s still succeeding.”

Watch this episode of Inside the Storm here.