The rise of non-consensual porn in Singapore, and the battle to stem its spread

Violated by image-based sexual abuse, some of these women are finding ways to do more than just damage control. The programme Undercover Asia speaks to several victims.

Intimate images are being leaked online without consent, invading privacy and destroying lives.

SINGAPORE: The digital space is a double-edged sword for social media influencer Christabel Chua.

It is where she sells lifestyle products and advertises to her 250,000-plus followers. But it is also where her biggest nightmare played out — when someone hacked into her ex-boyfriend’s cloud storage space in 2018 and leaked their sex videos online.

“I had people just sharing (them), blatantly and mindlessly. And when you hear of such things, you do feel very hurt … You wouldn’t wish it upon anyone,” she said.

“There were comments (like), ‘I hope she kills herself, I hope she dies’ … It replays in your head non-stop.”

The videos were shared on porn websites, forums and social media platforms. “You assume that the worst wouldn’t happen. But the worst might happen, and can happen,” added Chua, who is better known by her online moniker @bellywellyjelly.

The 29-year-old is a victim of non-consensual pornography, which refers to intimate images being leaked on the Internet without consent.

The problem is on the rise in Singapore, and the programme Undercover Asia finds out if anything can be done to stem the spread. (Watch the episode here.)

MULTIPLE PLATFORMS

The number of image-based sexual abuse cases seen by the Association of Women for Action and Research has doubled from 30 in 2016 to 64 in 2018. These include upskirting and revenge pornography.

Many more reports have been made to the police: For example, about 230 voyeurism cases involving hidden cameras in 2017, up from some 150 cases in 2013.

Nicole Lim, who tackles sexual harassment issues on her podcast, Something Private, learned about the harms of non-consensual porn while researching an episode — and has since kept track of the platforms spreading it.

Much of the content makes its way to porn websites, but some of it turns up on social media networks and chat groups, such as Tumblr and Telegram.

“Reddit’s a very popular place for people to share this kind of information. Another one that I’ve seen a lot of is Twitter,” cited Lim. “It’s graphic, literally everything is there, and there are a few thousand views.”

One of the most brazen examples is the SG Nasi Lemak Telegram group. It is no longer accessible but is said to have had more than 44,000 members, some of whom were sharing obscene photos and videos of women.

In October, four males were charged with distributing obscene materials, including upskirt photos, through this chat group.

“Non-consensual porn is definitely on the rise,” said Lim. “It can be attributed to several factors; the very big factor is technology.”

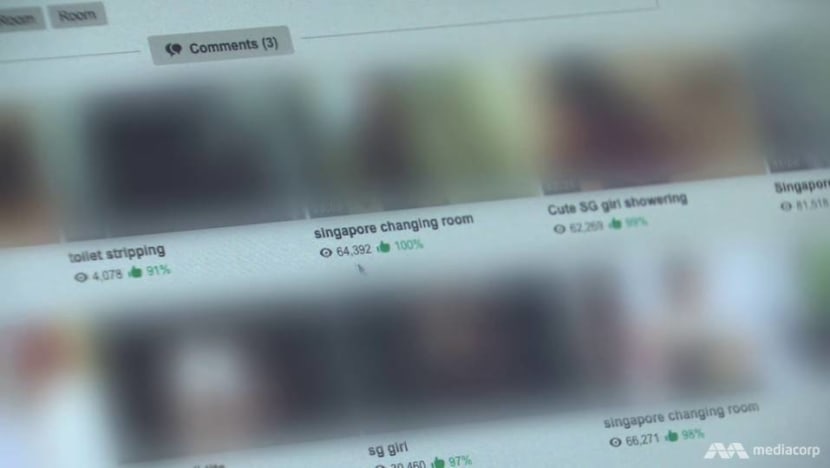

In many cases, hidden cameras are used to capture voyeur porn. And because victims often do not know a camera is pointed at them, there are more who have fallen prey than the numbers reported.

READ: Singapore’s voyeurism problem – what’s wrong with men, or the world?

READ: Spy cameras, illicit filming and upskirt photos: Are you being watched?

Spy camera manufacturer John Seng said the cameras have become smaller, and their video resolution much better.

“Most of the spy cams sold in the market are used for the wrong reasons: By … electronic peeping toms for upskirt filming. I’d say more than 90 per cent,” he added.

While the installation of hidden cameras is not illegal in Singapore, those who film a private act without consent can be jailed for up to two years, and may also be caned or fined.

VICTIMS FIGHTING BACK

Undercover Asia infiltrated several platforms frequented by voyeurs, some of whom boasted about the collection of videos they had secretly filmed.

One regular contributor, “Kinis”, who identified himself as a Singaporean, uploaded at least 35 upskirt videos in the prior three months. He shared how he took the videos, for example cautioning against getting too close to the victim.

He also said he had close shaves but was never caught. Asked if the risk was worth it, he replied: “After watching so many upskirt videos, it’s worth it to get your own.”

Some victims, however, are fighting back — like Elicia Yeo, who helped to crack the SG Nasi Lemak case with Benjamin Tang.

Her photos on social media were posted in the chat group, where members made sexual comments about her. Tang, meanwhile, wanted to help a friend who was affected similarly. So both joined the group to get those photos removed.

Both were shocked to find thousands of images of women, dressed and undressed. “They even taught you how to secretly take photos of girls, upskirt … Every second someone was posting something,” said Yeo, who made a police report.

Tang, a tech expert, programmed bots to join the group to collect information about the members, which he handed to the police. “These photos were being used in a manner that people definitely couldn’t have consented to,” he said.

Taking matters into her own hands was something undergraduate Monica Baey did last April, when she used social media to call for tougher action against the perpetrator who filmed her in the shower.

The police had given Nicholas Lim a 12-month conditional warning, and his university had suspended him for a semester. He ended up receiving a barrage of online harassment, but Baey stood by her decision.

“I don’t owe it to him to keep his name private. Too many perpetrators go unnamed, and get away with sexual assault because their victims feel bad,” she posted on Instagram.

“I want him to realise … how badly you can mess a person up just by filming them without their consent.”

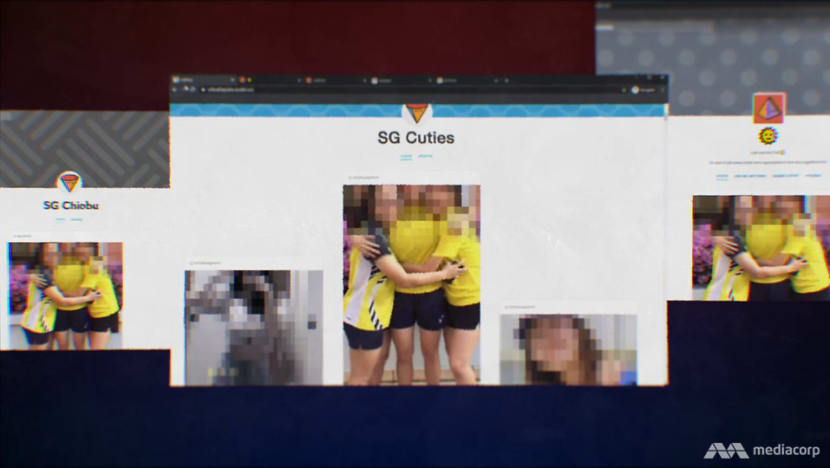

Non-consensual porn also includes digitally altering someone’s image in a sexually offensive way. Gia Lim is all too familiar with the trauma this brings.

She was preparing for her O Levels in 2015 when she discovered edited photos of herself on a Tumblr blog, accompanied by “sexually degrading” captions about her “going around and giving sexual favours”.

“None of this is true,” she said. “It made me feel very, very sick.”

She later discovered that one of her closest male friends had posted the content, but she was too distressed to pursue the matter.

She has since given talks about her experience as a victim of non-consensual porn and is working with the Education Ministry to raise awareness of this issue in schools.

TOUGH TO ENFORCE

Last year, Parliament passed the Criminal Law Reform Bill, in which sexual offences brought about by technological advances — such as voyeurism and “cyber flashing” — became criminalised.

READ: Voyeurism, ‘cyber flashing’ to be criminalised from January as legal reforms kick in

But the changes might be tough to enforce. Lawyer Adam Maniam from Drew and Napier thinks it would be unrealistic to expect the authorities to have the resources to investigate and prosecute all of these cases.

“Even if the person who’s committed the act is convicted,” he said, “the content … could still be hosted on various sites that are international.

“So even if the court were empowered to order these sites to take down the material, there could still be issues with enforcing.”

There are, however, companies that can help victims remove their digital footprint. Lawmence Wong, regional director of Internet Removal Asia in Kuala Lumpur, said his team can usually remove 80 per cent of the links within two to four weeks.

But there is no guarantee that the content stays removed for good. “This is something out of our control,” he said. “If the website is restructured … it might appear again. So it’s important to have a monitoring process.”

Content removal is not cheap either: Each link can cost between S$300 and S$550 to remove. And for many victims, the damage is already done, with lasting effects.

Lim likened the process of removing such content to a digital whack-a-mole, whereby “you think you really got it, then there’s one more that pops up somewhere else”.

“I’ve done almost everything that I could,” she said. “I either struggle or I have to, in some ways, let it go … It’s time to move on.”

For Chua, even though the hacker who had stolen and circulated her private videos was arrested, there is no closure.

“The Internet is ever-living. So I wouldn’t say that there’d be a day when you can’t find anything any more, whether it’s for me (or) anyone else,” she said.

“One of the hardest things to accept is that they’ll always be there.”

Watch this episode here. Undercover Asia is telecast on Saturdays at 9pm.