Commentary: We need some give-and-take when it comes to after-hours work communications

Many of us are expected to be “on” 24/7 since shifting to working from home, but workers are pushing back and don’t want to be contacted after hours. Is this feasible? Mayank Parekh has suggestions.

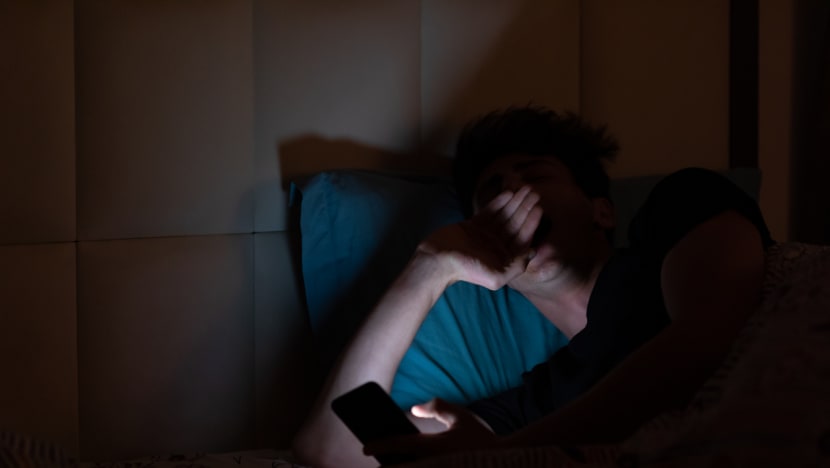

The embrace of work-from-home did not happen overnight, as companies shared how it was a process of trial and error as they searched for the optimal arrangement. (Photo: TODAY/Nuria Ling)

SINGAPORE: We are approaching 18 months since Singapore first implemented circuit breaker measures on Apr 7, 2020. This brought to a grinding halt the daily commute for many, as working from home became the default.

Initially, employees relished the flexibility and productivity supposedly increased.

But the true test soon became clear: The blurring of lines between work and home resulted in the realisation that mental wellness has been neglected all this while.

As more workers complained of the stress of a 24/7 work culture, companies began sitting up and taking notice. Several have embarked on initiatives such as virtual group fitness and yoga classes, talks about mental wellness and nutrition to alleviate mental stress to aim for better employee well-being in the current environment.

As companies course-corrected and employee well-being programmes rapidly gained popularity, mental wellness soon became a hot topic.

For essential employees unable to work from home, initiatives such as tightened protocols and physical measures at the workplace to control transmission of virus, better air circulation in enclosed work environments, and professional cleaning contractors to regularly disinfect supplies and common surfaces provided some measure of reassurance.

For employees working from home there is a recognition that remote work could lead to longer work days for employees without them realising it. Bloomberg reports that people who work from home clock in three hours more each day than before.

Employees are being encouraged to build regular breaks into their day, take personal time off, leave their desks when they needed to re-charge, plan time to socialise with co-workers and check in on one another.

RIGHT TO DISCONNECT?

These trends are gaining ground in Singapore. A Tripartite Standard on Work-Life Harmony was launched in April, urging firms to provide employee support initiatives such as flexible work arrangements, family days and more leave days for those with caregiving responsibilities.

Another important area cited is training for management to lead with empathy and look out for potential signs of mental health issues. There is even an online survey tool iWorkHealth developed by the Ministry of Manpower where companies receive an aggregated report on their key workplace stressors while employees receive a personalised report on mental well-being and workplace stressors.

However, some employees are pessimistic – they cite instances where texts, emails or calls are regular during after-hours and weekends. They are concerned that the need to maintain a competitive economy and the entrenched culture among workers here to be available round the clock may be insurmountable obstacles.

But are they really zero-sum? There is a quiet stirring the answer is no.

Labour Member of Parliament Melvin Yong (Radin Mas) even suggested adopting a “right to disconnect” law to help employees have protected time to rest and recharge, citing that France is one country which successfully implemented such a legislation.

Mr Yong argued that rest is linked to worker productivity.

In reality, things are not so simple. There must be give and take on both sides.

Locally based employees of global multinational corporations that operate across time zones are often required to attend after-hours conference calls. Those in essential services need to always remain contactable.

This has nothing to do with a 24/7 work culture and everything to do with exigencies of service. For instance, working longer hours to meet a deadline or to attend to unforeseen crisis events are part of many people’s job scopes.

But this does not mean employees should simply accept that their work and personal lives will always meld and they have no choice in the matter.

Increasingly, workers are realising that while they may have to attend to after-hours calls, texts or emails, they want greater flexibility in their work hours.

For instance, some prefer to block out time during the day to focus on their kids as they juggle home-schooling or childcare, and then come back to complete work assignments in the evening hours.

WHAT IS UNACCEPTABLE?

But the challenge remains as to how much of this flexibility leads to an unhealthy expectation of staff to be “always on”? What is the threshold that makes this unacceptable?

Traditionally, the relationship between employer and employee is governed by an employment contract. The employer provides compensation and tenure in return for fulfillment of job responsibilities, usually supported by an employee handbook.

This works well in organisations that have historically operated with centralised and rigid work models. However, to adapt to a new reality defined by volatility, uncertainty, complexity and ambiguity, such firms must transition into more decentralised and fluid work models.

More than ever, employee success today goes beyond just setting key performance indicators to achieve and has to fold in collaboration, influencing, creativity to respond to the changing needs of the business, and occasionally rising above and beyond the call of duty.

Employees, on the other hand, want to be treated fairly and with respect. They want the flexibility to decide where and when work gets done, so long as the work is done. They seek meaning and purpose in work that aligns to their personal values.

So how can the two meet in the middle?

Perhaps in addition to a traditional employment contract, companies should think about adding a social contract that binds both parties to an agreed set of rules of behaviour.

These could include adopting an inclusive mindset towards employees from different backgrounds, creating a work culture that respects individual needs of employees, treating employees fairly and with dignity, creating a conducive workplace environment that is non-discriminatory, safe and friendly to employees, implementing HR practices such as flexible work arrangements, providing important benefits for wellbeing, and training and education support to keep their skills and knowledge up-to-date.

Patagonia, a 40-year-old American company that manufactures and retails outdoor clothing is one example. It offers flexible work hours and job sharing.

The founder, when he was in active leadership, took months off every year, during which he was unreachable. Granted, this may not be feasible nor practical in some contexts.

But it is the ethos of his leadership we can take a leaf from. He put the success of his company down to flexibility in how he managed his team who are independent workers allowed to decide when they need time off to spend with their families, without sacrificing business needs.

The idea of the social contract (borrowed from political philosophy) is that everyone in an organisation is there for the collective benefit of all. For the employer, a social contract is an opportunity to be committed to policies, programmes and practices which improve the well-being of their staff.

It means the leadership has to walk the talk: If bosses say they will respect a staff’s personal time off, it should be adhered to with as little exception as possible.

For the employee, it is an opportunity to personalise the work experience to take into account evolving needs and aspirations but to also be aware that their personal circumstances must align with what is required of them as engaged, talented workers for their organisations.

In other words, this give-and-take is critical to more sustainable long-term growth.

In today’s tight labour market, a compelling social contract may just be the “beyond profits” strategy needed in organisations to attract, retain and sustain talent.

Mayank Parekh is the CEO of the Institute for Human Resource Professionals (IHRP) which aims to professionalise and strengthen the HR practice in Singapore.