Commentary: China’s energy crisis shows just how hard it will be to reach net-zero emissions

China has been cracking down on coal in its bid to decarbonise but coal still generates around two-thirds of its electricity so when a hotter than usual summer came around, things took a turn, says an economics professor.

FILE PHOTO: A general view shows the Wujing Coal-Electricity Power Station in Shanghai on Sep 28, 2021. (AFP/Hector Retamal)

BIRMINGHAM: As the world prepares to discuss more aggressive cuts to carbon emissions at the UN’s COP26 climate conference in Glasgow, China has just sent out the worst possible advance signal.

It is going to loosen restrictions on coal mining in the final three months of the year in response to an energy crisis which has seen nationwide blackouts and many manufacturers shutting down production lines in recent weeks.

China will now extract more coal in 2021 than the 3.9 billion tonnes it extracted in 2020, as well as quietly importing more from places like Australia. The move flies in the face of President Xi Jinping’s strong rhetoric about decarbonisation, including a very recent commitment to stop building coal-fired power stations in other countries.

And it raises questions about the nation’s ability to make good on the tough carbon reduction targets in its 14th five-year plan to 2025.

So how did China get into this situation, and what does it mean for the world’s efforts to reach net zero?

WHY THE LIGHTS WENT OFF

China has a so-called dual control target for national environmental protection, which is about cutting both energy consumption and the amount of energy that goes into each unit of GDP (known as energy intensity).

Having made impressive strides forward in the 2015-2020 period, China is now aiming to cut energy intensity by 13.5 per cent by 2025 and to cut carbon emissions per unit of GDP by 18 per cent, with a view to bringing overall carbon emissions down by 2030.

To this end, China has been cracking down on coal, which still generates around two-thirds of its electricity. The state has been shutting down small and inefficient mines and putting restrictions on coal production. Consequently, coal output has been falling in many months in 2021, while coal imports were also low.

But this drove up the price of coal, and electricity-generating companies could not pass on the costs to consumers because of national price caps. Faced with generating electricity at a loss, major players have simply stopped producing.

To make matters worse, China has had an exceptionally hot summer (which itself is being blamed on climate change). The dry windless weather has meant that China’s wind and hydroelectric power have been generating less electricity than usual.

The result has been outages that have seen many families reduced to candle-lit dinners, traffic lights failing, and unlucky people getting trapped in elevators between two floors.

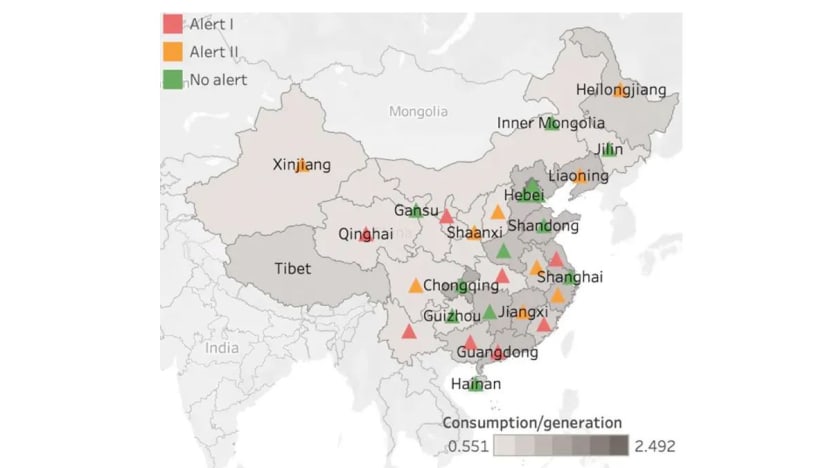

Meanwhile, provinces have been given specific targets and deadlines to help achieve the emissions targets, many of them related to electricity consumption. Beijing “name and shames” laggard provinces with yellow (bad) and red (very bad) alerts, represented by triangles in the map below.

As with other hard targets in China, missing them can have serious implications for a local official’s career prospects. So, in response to these alerts, several provinces have been imposing electricity usage restrictions, particularly on companies in energy-intensive industries like steel, printing, textiles, wood, chemicals, plastics and goods manufacturing.

In many cases, companies were indiscriminately told to restrict production to two or three days a week – compounding the problems from generating companies shutting down power.

Coming at a time when demand for Chinese-made products has been rising sharply because global consumer spending is recovering from the pandemic, this is one more hit to global supply chains.

They are already having to deal with too few semiconductors, workers, containers and ships – to name only a few. Apple, Tesla, Microsoft and Dell are among the big names saying their supply chains are now also being hit by China’s energy crisis.

Can China keep its bold promises to get to net-zero emissions? Chen Gang, Assistant Director at the NUS East Asian Institute, gives his take on The Climate Conversations:

SUPPLY CHAINS ARE FRAYING

Not only is China loosening restrictions on coal production for the rest of 2021, but it is also making special bank loans available for mining companies and even allowing safety rules in mines to be relaxed.

This is having the desired effect: On Oct 8, after a week in which the markets have been closed for a national holiday, domestic coal prices promptly dropped by 5 per cent.

This will presumably ease the crisis as the winter approaches, notwithstanding the government’s embarrassment going into COP26. So what lessons can be learned for the road ahead?

First, supply chains are fraying.

Since the disruptions to global supply chains caused by COVID abated, the mood has been one of getting back to normal. But China’s power struggle illustrates how fragile they can still be.

The three provinces of Guangdong, Jiangsu and Zhejiang are responsible for nearly 60 per cent of China’s US$2.5 trillion exports. They are the nation’s biggest electricity consumers and are being hardest hit by the outages.

In other words, so long as China’s economy (and by extension the global economy) is so dependent on coal-fired power, there’s a direct conflict between cutting carbon and keeping supply chains functioning. The net-zero agenda makes it very likely we will see similar disruptions in future. The businesses that survive will be the ones that are prepared for this reality.

A CENTRALISED ECONOMY CAN WORSEN AN ENERGY CRISIS

Second, command economies have drawbacks.

In China, the fixed electricity price cap prevented prices from rising even when it meant producing electricity at a loss. The power shortages have seen some big manufacturers surviving by hiring private generators (meaning more carbon emissions), while smaller players who can’t afford generators have been unable to fulfil orders and are going bust.

With large manufacturers looking to recoup the cost of hiring generators, and fewer goods being exported overall, global consumer prices will go up.

Contrast this with a market economy like the UK, which is having its own energy crisis because of high gas prices. It too has consumer price caps for electricity, but it has been quicker to allow them to rise.

This won’t save many smaller energy providers, who have too many customers on unprofitable fixed-tariff contracts and don’t own any of the energy network, so can’t offset their losses by wholesaling energy to other providers at more expensive prices.

Businesses and consumers are going to suffer too from higher energy bills, but there are no power cuts so overall the disruption to the economy is much less.

YET CHINA REMAINS SERIOUS ABOUT DECARBONISATION

Finally, China is serious about decarbonisation.

Despite its temporary climbdown over coal-mining, China’s resolve over decarbonisation is worth commending. As pointed out by analysts at Nomura bank: “Beijing’s unprecedented resolve … could result in invaluable long-term gains, but the short-term costs to both the real economy and financial markets are substantial.”

In short, the world is facing a real crisis. The consequences from climate change are appearing more frequently than before. Yet for all the exciting low-carbon technologies, we are still some way from being able to rely on them to cut carbon emissions without undermining the economy.

The good news is that at least many countries including China are now committed to cutting emissions and are willing to collaborate to achieve this.

Whatever the difficulties ahead, collaboration is surely the key to net zero.

Jun Du is Professor of Economics, Centre Director of Centre for Business Prosperity (CBP) at Aston University. This commentary first appeared in The Conversation.