Commentary: Not Islamophobic to deny Indonesia preacher entry into Singapore

Some followers of Indonesian preacher Abdul Somad Batubara claim he was denied entry due to Islamophobia, but Singapore has acted consistently against behaviour that may potentially jeopardise religious and communal harmony, says ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute's Dr Norshahril Saat.

Supporters of a Indonesian preacher Abdul Somad Batubara hold a protest next to Somad’s photograph in front of the Singapore embassy in Jakarta on May 20, 2022, after he was refused entry to Singapore on May 16. (Photo: AFP/BAY ISMOYO)

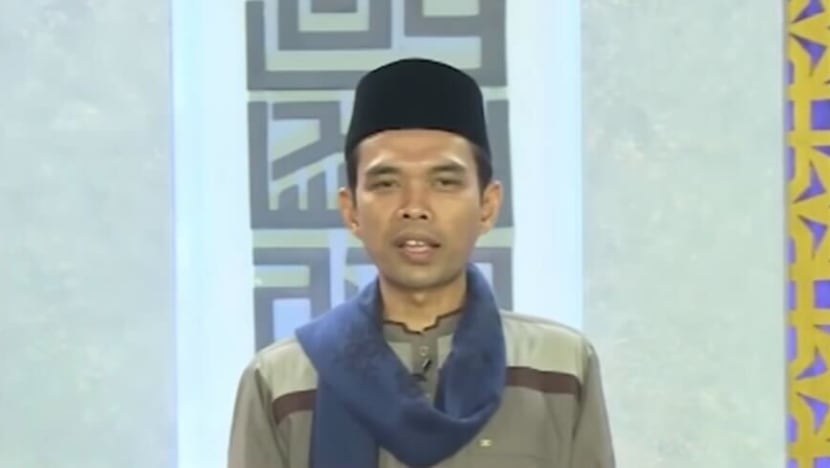

SINGAPORE: The Singapore Government’s decision to deny Indonesian preacher Abdul Somad Batubara entry into the country on Monday (May 16) has created some buzz among netizens in Indonesia and Singapore. Somad, who was planning to enter Singapore for a social visit with his family and friends, was stopped at Singapore immigration.

Some of his ardent followers declared Islamophobia, or the prejudiced fear of Islam, as the reason for the incident. Somad immediately took to social media to share his “plight” and complain about the way he was treated, including being asked to wait in a 1m by 2m room.

This garnered sympathy among his followers, who later spammed the Facebook pages of Singapore politicians and agencies with negative comments. Among the Facebook pages affected were those of Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong, Senior Minister Teo Chee Hean and President Halimah Yacob.

Targeting the Singapore leaders in this way only shows that Somad’s sympathisers are digitally literate and savvy enough to target Singapore leaders who command a significant online presence.

VIEWS NOT IN SYNC WITH MULTIRACIAL MULTIRELIGIOUS SINGAPORE

To be sure, Somad was not deported from Singapore as claimed by his followers because he had not even entered Singapore. On May 16, he was stopped at the Tanah Merah Ferry Terminal and returned to Indonesia along with his six travel companions on the same day.

According to Singapore’s Ministry of Home Affairs, his views are not in sync with Singapore’s multiracial and multireligious underpinnings.

Related:

Among others, Somad considers suicide bombing to be permissible in the Israel-Palestinian conflict and believes in the martyrdom of Palestinians who carry out such attacks. He has also made derogative remarks about Christianity by saying that “infidel jinns” (or spirits) live on the crucifix.

In the same vein, he has cautioned Muslims against travelling in ambulances with the symbol of the crucifix (read: the Red Cross). He has also characterised Shi’ism as dangerous and forbade Muslims from wishing non-Muslims “Merry Christmas”.

Even if Somad were allowed to enter Singapore, he would not be permitted to preach without a Miscellaneous Work Pass. He would also not be able to preach at local mosques without a permit or approval from the Islamic authorities in Singapore.

IN CONTRAST WITH OTHER RESPECTED SCHOLARS

Yet because of the incident, his followers have accused the Singapore government of being disrespectful toward the ulama (Islamic religious scholars), a group highly respected by Muslims.

The reality is that Somad is merely a popular preacher and not a scholar as his followers claim. His sermons are easily accessible online and his speeches cover a range of issues, mostly on rituals. In fact, his popularity hinges more on his wit, humour and charisma rather than his depth of Islamic scholarship.

In contrast, respected Islamic scholars are marked by their exposure and openness to nuanced ideas and beliefs and would avoid making derogatory remarks against other faiths.

Somad’s digital presence has contributed significantly to his popularity in Indonesia – and ultimately his reach beyond Indonesian shores – over the more qualified Indonesian ulama. His simple, if not simplistic, messages about Islam have fuelled his rise.

In the 1970s, when the region saw an Islamic resurgence, the dominant religious orientation among Muslim elites was traditionalism, where certain religious ideas were considered to be unquestionable and fixed, regardless of historical context. Often, Islam is understood in terms of permissibility (halal) or non-permissibility (haram).

In contrast, note the approach of moderate and notable Indonesian Islamic scholars such as Quraish Shihab, Nurcholish Majid, Abdurrahman Wahid and Ahmad Shafii Maarif, who are more appreciative of diverse opinions. For these scholars, the evolution of Islam is seen through a historical lens and Islam is placed within a modern context.

The point is that Somad was not singled out by the Singapore authorities by virtue of his religion. The Muslim community is thriving in Singapore and is free to practice its religion, while Singapore’s Government respects the community’s key institutions including mosques and a Syariah court system.

CONSISTENT ACTION REGARDLESS OF PERPETRATOR'S FAITH

Singapore has consistently prohibited any behaviour, regardless of the perpetrator’s faith, that may potentially jeopardise the country’s religious and communal harmony. In 2017, a Muslim preacher, Imam Nalla Mohamed Abdul Jameel, was deported from Singapore after making offensive remarks about Christians and Jews in one of his sermons.

The imam, who originated from India and had served a local mosque for seven years, was slapped with a fine of S$4,000. A video was circulated online showing him reciting a prayer for God to save Muslims from Jews and Christians. He later apologised and expressed regret for his actions.

In the same year, American-Muslim preacher Yusuf Estes was not allowed to enter Singapore because he had remarked in 2012 that Islam neither celebrated the holidays of other faiths nor allowed Muslims to wish others “Merry Christmas”.

In 2019, Christian American preacher Lou Engle was not allowed to come to Singapore because he made offensive remarks against Muslims at a church. In an article, he was alleged to have said: “Muslims are taking over the south of Spain … But I had a dream, where I will raise up the church all over Spain to push back a new modern Muslim movement.”

Recently, Singapore agencies banned the movie Kashmir Files for its “provocative and one-sided” views of Muslims in the ongoing conflict in Kashmir. According to the agencies, the movie could have led to misrepresentations of faiths and provoked enmity between Muslims and Hindus.

The Singapore Government is clearly strict in preventing terrorist activities and discouraging radical ideas from taking root. Apart from hard measures, the Government also takes a softer approach, carrying out dialogues and networking with different faith communities to encourage mutual appreciation and understanding.

Moreover, the authorities are quick to weed out any forms of non-violent extremism, with Somad’s and Engle’s cases as clear examples.

While it is true that Somad does not support terrorist groups such as Islamic State, some of his views may be disruptive to Singapore’s multireligious harmony. Barring Somad from entry is an unequivocal and symbolic indication of Singapore’s anti-extremist stance.

This, however, is not a catch-all solution because online spaces cannot be subject to complete control. Even if laws, such as Singapore’s Protection from Online Falsehoods and Manipulation Act (POFMA), may allow the authorities to remove potentially damaging or inflammatory online content, the speed and spread of fiery sermons via social media would require a level of vigilance and manpower resources that would be challenging to muster.

Thus, government and society must continue working together to prevent any extremism that denies freedom of religion and diverse opinion, to ensure that pluralism and the preservation of common spaces in Singapore are maintained.

Dr Norshahril Saat is a Senior Fellow at ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute. This commentary first appeared in the Institute's blog The Fulcrum.