Commentary: Why inflation is sweeping the world dramatically, except Asia

Better handling of the COVID-19 pandemic is the reason why Asia has not seen such sharp price rises worrying Europe and the Americas, says the Financial Times' Robin Harding.

TOKYO: The world is experiencing a dramatic bout of inflation. Except for the places where it is not.

Sharp price rises in the United States and United Kingdom — where the headline consumer price index is up by 6 per cent and 4 per cent, respectively — have raised fears of a disastrous mistake by central banks and a return to the chronic inflation of the 1970s.

But across much of Asia, price rises are subdued. That divergence holds lessons for economic policy, now and in the future.

In China, the CPI is up by 1.5 per cent compared with a year ago, while in Japan, as usual, inflation is roughly zero. In Australia, the headline CPI may be up by 3 per cent, but underlying inflation of 2.1 per cent is towards the bottom of the central bank’s target range.

Only two big emerging markets in Asia have inflation running above 5 per cent — Sri Lanka and Pakistan — compared with many in Europe and South America. Seen from Tokyo, Beijing or Jakarta, the global surge in inflation does not look global at all.

This is true even though Asia imports a lot of energy and has suffered the same jump in prices for oil, gas, coal and other commodities as everywhere else in the world.

The reason Asia’s inflation is mild and not severe comes down to one simple factor: It handled the COVID-19 pandemic better than the rest of the world.

FEWER DRAMATIC SWINGS IN CONSUMPTION

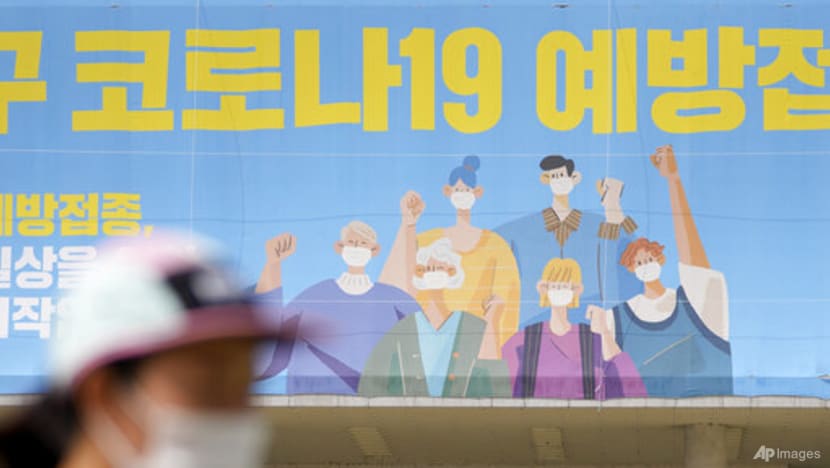

Across most of the region, countries managed to avoid compulsory lockdowns altogether, like South Korea; limit them in scope and duration, like China; or delay such measures until deep into 2021 when vaccines were becoming available, like New Zealand.

The consequences of this relative success are now playing out in several ways.

On the demand side of the economy, Asia experienced fewer of the dramatic swings in consumption from services to goods and back again that marked the experience of the US and Europe, as they went into lockdown and came back out again.

If you were never locked up at home, you never felt the need to buy a treadmill, a new television and enough lumber to deck the back yard.

If you could keep up regular haircuts, dental checks and drinks with friends, meanwhile, you had no need to rush out to the hairdresser, the dentist and the nearest bar when the economy reopened.

Asians have also, by and large, been more cautious than Europeans or Americans when their economies do open up.

In Japan, for example, elderly households account for almost 40 per cent of consumption, as Bank of Japan governor Haruhiko Kuroda noted in a recent speech. But even though Japan’s retirees are now largely vaccinated, their consumption of services has not yet returned to normal, let alone exhibited a post-pandemic boom. Smaller swings in demand meant less pressure for supply to respond.

ASIA, THE WORLD'S FACTORY

But the COVID-19 pandemic has also illustrated the consequences of Asia’s global manufacturing dominance. Since the region makes most of the world’s stuff, it can more easily keep itself well-supplied.

Gareth Leather and Mark Williams at Capital Economics discuss some of these factors in a recent note. For example, whereas the cost of shipping a container from China to Europe has risen fivefold since COVID-19 hit, the cost of shipping it within Asia has only doubled.

When COVID-19 prompted factory closures, Asian companies had a greater choice of alternative suppliers within the region, meaning less disruption to supply.

In the automobile sector, South Korea and China were able to make sure domestic producers had priority access to scarce semiconductors. There is double-digit inflation for automobiles in the US. In East Asia, prices have barely risen.

One of the biggest differences between Asia and the US is labour supply. When COVID-19 hit, many workers in the US were laid off, resigned from their job to care for children affected by school closures, or else chose to quit to avoid catching the virus.

The result has been a lasting hit to labour supply. That is pushing up wages in the US and UK — a big reason for concern about inflation. There is little sign of a similar wage acceleration in Asia.

The avoidance of lockdown — or the use of wage subsidies to keep workers in their jobs through the worst of it — made the whole event less traumatic.

In Australia and New Zealand, participation in the labour force has been near record levels. “Labour hoarding,” Kuroda said, “has enabled Japanese firms to maintain capacity to swiftly increase supply even when demand has risen due to the resumption of economic activity”.

Without immediate inflation to worry about, Asia’s central banks can nurse the economic recovery. Those raising interest rates, such as New Zealand and South Korea, have done so either because the economy is at full employment and they fear it will overheat, or because of concerns about financial stability.

The Reserve Bank of Australia has said confidently it does not expect to raise interest rates in 2022. The Bank of Japan, as usual, does not expect to raise interest rates any time in the foreseeable future.

For central banks in Europe and the Americas, Asia’s experience adds weight to the view that their high inflation was caused by disruption from the pandemic. That disruption should abate.

But western central banks cannot be as sanguine as their Asian counterparts: If wages accelerate, then transitory pressures on inflation will become persistent.

Differing choices in the handling of COVID-19 had many consequences. Those for inflation are now becoming apparent.