commentary Commentary

Commentary: Joe Biden is reshaping America and the world in his image

US President Joe Biden’s early foreign policy offers promise, showing discipline, a focus on Asia and pressing issues on trade, taxation and more. The key question is whether this will last, says Dr Prashanth Parameswaran.

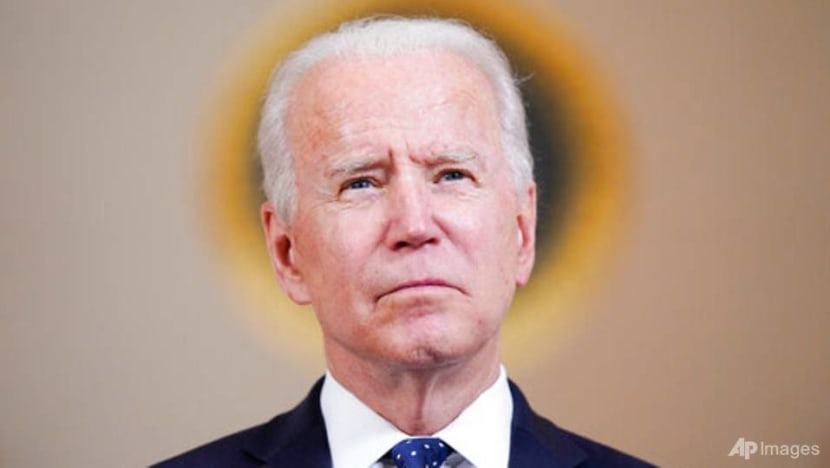

President Joe Biden speaks on Apr 20, 2021, at the White House in Washington, after former Minneapolis police Officer Derek Chauvin was convicted of murder and manslaughter in the death of George Floyd. (Photo: AP/Evan Vucci)

SINGAPORE: As US President Joe Biden approaches his 100-day mark in office, he and his team seem to be off on a good start to their management of US foreign policy.

They are hewing to a disciplined foreign policy approach that prioritises Asia relative to other regions, re-engages on selective priorities such as climate change, ties elements of US domestic renewal to international engagement and defers on some divisive issues.

While the disciplined approach bodes well, it remains to be seen whether it will last through his tenure as president.

READ: Commentary: Joe Biden’s quietly revolutionary first 100 days

A DISCIPLINED US FOREIGN POLICY

Attempted discipline is not new to US foreign policy. George W Bush pledged a humble foreign policy but diverted US attention to the Middle East after the September 11, 2001 attacks with twin wars in Afghanistan and Iraq.

Barack Obama was criticised for taking discipline too far: Refusing to be tougher on Beijing despite its rising assertiveness and refraining from intervening in Syria lest it drag Washington into conflict and undermine domestic priorities like healthcare.

A disciplined foreign policy is not something one expects to associate with Mr Biden, given the man’s off-the-cuff style and emotive brand of politics.

READ: Commentary: After Trump, what future awaits the US Republican Party?

READ: Commentary: We need to talk about how Donald Trump’s presidency wasn’t a complete disaster

Yet he and his team seemed to understand that given the moment they found themselves in – with the fallout from some of Donald Trump’s America First policies and a once-in-a-century pandemic – discipline is an important trait to embrace facing a range of challenges not seen since World War II.

This tendency arguably took shape even before he took office. His campaign platform signalled a domestic-focused foreign policy under the banner of a “foreign policy for the middle class”.

At his inauguration, Mr Biden enumerated the four areas where the domestic focus that undergirds America’s approach would lie: The pandemic, economic crisis, climate change and racial injustice.

There was no guarantee this discipline during the campaign would live on once Mr Biden began governing, even though structural factors, such as a razor-thin Congressional majority, have acted as guardrails to some degree.

But as his administration reaches its 100-day mark, it is clear that a deliberate effort is being made to reinforce a message of foreign policy discipline.

REFOCUSING ON ASIA

First, Mr Biden has prioritised Asia relative to other regions. Realising the need to clearly signal an Asia-first foreign policy early on, he quickly held the first-ever Quad summit in March and slotted in Japanese Prime Minister Yoshihide Suga as his first White House guest in April.

These moves helped counter a narrative that the lack of Asia expertise among the administration’s top personnel may limit Mr Biden’s engagement with the region.

Within that approach, the administration has also signaled a prioritisation of allies and partners rather than let itself be consumed by how it might differ from Mr Trump’s China approach.

READ: Commentary: Trump’s playbook on China in the South China Sea has some lessons for the Biden administration

READ: Commentary: Is it too late for the US to join the CPTPP?

The administration’s holding of the Alaska meeting in March right after engagements with treaty allies in Japan and South Korea was a case in point and a part of what Mr Biden’s White House coordinator for Indo-Pacific Kurt Campbell had previously called crafting a “stable competition” approach towards Beijing from a position of strength.

Meanwhile, more peripheral agenda items in the president’s inbox are being de-emphasised alongside this Asia-first foreign policy.

For instance, when Mr Biden announced the withdrawal of US troops from Afghanistan on Apr 14, he specifically noted that US resources would be best spent on other priorities including competing with China and shaping norms on cybersecurity and emerging technologies – “the battles for the next 20 years, not the last 20”.

READ: Commentary: Why is former Chinese premier Wen Jiabao’s eulogy about his mother being censored?

AMERICA IS BACK – IN GLOBAL AFFAIRS, DEMOCRACY AND CLIMATE CHANGE

Second, Mr Biden and his team have quickly re-engaged with the world on selective foreign policy priorities.

The goal, as administration officials have repeated over past few months, is to signal that “America is back,” and, more specifically, that diplomacy is at the centre of foreign policy relative to the Trump years in a handful of areas clearly be seen as producing value for the American people.

Top of mind has been climate change, as evidenced by Mr Biden’s reentry into the historic 2015 Paris climate accord during his first few hours in office and the early announcement of the Leaders’ Climate Summit on Jan 27.

That has been spearheaded by the tireless diplomacy of John Kerry, who holds a new Cabinet-level position of special presidential envoy for climate, and Mr Biden’s domestic climate czar Gina McCarthy who ensures the climate priority is also intimately tied to US domestic.

READ: Investments to tackle climate crisis make ‘very good economic sense’: COP26 president

Another case in point is democracy and human rights. It is no coincidence Mr Biden’s introduction to his Interim National Security Strategic Guidance, issued on Mar 3, began with reinforcing the importance of democracy both at home and abroad at a time when autocracy appears to be on the rise.

Several commitments, including the holding of a Democracy Summit, have yet to be realised, and the balance between ideals and interests that each administration needs to strike will take a while yet to play out.

But the administration’s restoration of consistency and calibration on issues ranging from the crisis in Myanmar to Russia’s treatment of its opposition offers early promise about discipline on this front.

READ: Commentary: Defiance in Myanmar’s diplomatic ranks threatens the military’s power

REWRITING THE RULES OF GLOBAL TAXATION AND TRADE

Third, the administration has tied elements of US domestic renewal to international engagement in an attempt to build support for its Foreign Policy for a Middle Class.

As Mr Biden noted in his foreign policy remarks at the State Department in February: “There’s no longer a bright line between foreign and domestic policy. Every action we take in our conduct abroad, we must take with American working families in mind.”

A case in point is US tax policy. Here, the Biden administration is aspiring to secure support for a global minimum corporate tax rate abroad to maintain US competitiveness.

It looks to raise the US minimum tax rate at home to pay for its domestic agenda, which includes the US$1.9 trillion COVID-19 relief bill signed on Mar 11 and a US$2 trillion infrastructure plan being mulled.

Another is supply chains. Mr Biden’s Feb 24 executive order sets out a 100-day review which includes partnering with key US allies to build more resilient supply networks less vulnerable to disruptions by competitors in areas including semiconductors, electric-vehicle batteries, rare earths and pharmaceutical products.

Supply chains have factored heavily into the Biden administration’s discussions with allies and partners, including the Quad Summit with Australia, India and Japan.

READ: Commentary: Is China too big to tame? No easy answers to Quad’s central challenge

REINING IN DIVISION

Fourth, Mr Biden and his team have deferred on some divisive issues in the name of preserving their focus on key priorities at the outset.

Most notably, he has punted on entirely and quickly reversing Trump-era decisions that could quickly eat up his political capital in recognition of the domestic political environment.

For instance, on trade, he has signaled some continuity with Trump’s America First policies, as evidenced by some of his early moves including signing an executive order strengthening US Buy American policies.

His US Trade Representative, Katherine Tai, has also treaded carefully, articulating a domestic-focused “worker-centred trade policy”.

A similar trend can be observed with respect to immigration. While Mr Biden had initially pledged to raise refugee admissions back up from Trump’s historically low cap early on, he backtracked on his decision this month and delayed an increase, in part due to rising criticism on the surge of migrant children at the border with Mexico which could distract from his domestic priorities.

STILL EARLY DAYS

To be sure, it is still early days. It remains to be seen if the Biden administration will be able to maintain its foreign policy discipline.

Some of the approaches to key foreign policy issues it faces, including Iran, North Korea and terrorism, have yet to be laid out.

Furthermore, a key litmus test of discipline is whether Mr Biden and his team can keep focused on their priorities even when confronted by a new foreign policy crisis.

Yet given the vast array of challenges the administration faced at the outset and Biden’s past difficulty in keeping on message, the early foreign policy discipline is nonetheless noteworthy.

As we see other engagements shape up during the course of the year – from Mr Biden’s address to the joint session of Congress on Apr 28 to potential overseas visits as the world gradually reopens – this will be an important test to watch.

Dr Prashanth Parameswaran is Director of Research at BowerGroupAsia, a strategic advisory firm focused on the Asia-Pacific.