Commentary: We should eat more plants but countries subsidise meat and dairy farming

More than US$200 billion of public money go to farmers every year, and what they choose to grow has a great effect on the environment and our health, says an Oxford researcher.

OXFORD: The global food system is in disarray. Animal agriculture is a major driver of global heating, and as many as 12 million deaths from heart disease, stroke, cancers and diabetes are each year connected to eating the wrong things, like too much red and processed meat and too few fruits and vegetables.

Unless the world can slash the amount of animal products in its food system and embrace more plant-based diets, there is little chance of avoiding dangerous levels of climate change and mounting public health problems.

Agricultural subsidies help prop up a food system that is neither healthy nor sustainable.

Worldwide, more than US$200 billion of public money (that is, money collected through taxes) is given to farmers every year in direct transfers, usually with the intention of supporting national food production and supply. This might not be a problem in itself – after all, we all need to eat.

But the way governments provide subsidies at the moment exacerbates the health and environmental issues of food production. That’s one of the findings of a new study published in Nature Communications by my colleague Florian Freund and me.

WHAT AGRICULTURAL SUBSIDIES ARE SPENT ON

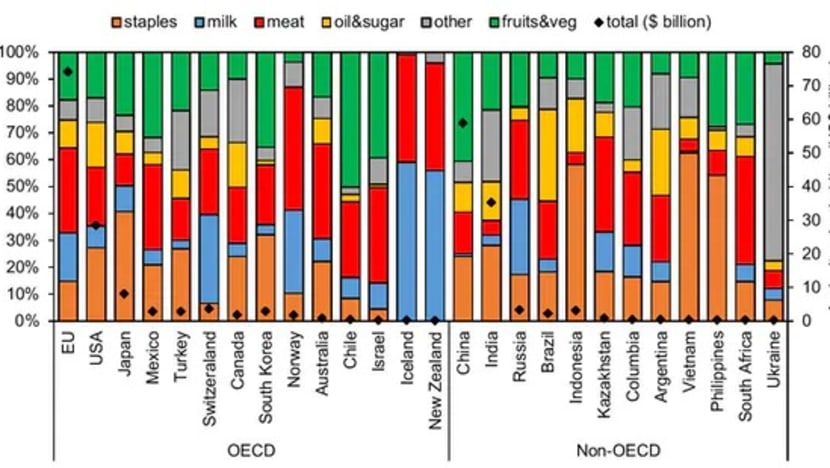

According to our analysis, about two-thirds of all agricultural transfer payments worldwide come without any strings attached. Farmers can use them to grow what they like.

In practice, this means every fifth dollar is used to raise meat, and every tenth dollar to make dairy products – the kinds of foods farmers have grown used to producing but which emit disproportionate amounts of greenhouse gas emissions, and which are also linked to dietary risks such as heart disease and certain cancers.

Farmers use another third of these payments to grow staple crops such as wheat and maize, and crops used for producing sugar and oil.

These are foods that are already produced and consumed in large quantities and that, if anything, should be limited in a healthy and sustainable diet.

Less than a quarter of transfer payments are used to grow the kinds of foods that are good for human health and the environment, and which a healthy and sustainable food system would need much more of: Fruits, vegetables, legumes and nuts.

Based on this breakdown, it’s clear there is plenty of room for improving how governments and farmers issue and spend agricultural subsidies. We decided to look at alternatives, and compare how they might work in the real world.

Related:

REFORMING SUBSIDIES COULD INCREASE FRUIT AND VEGETABLE PRODUCTION

We combined an economic model which tracked the knock-on effects of altering subsidies on food production and the food people eat with an environmental one which compared changes in resource use and greenhouse gas emissions – plus a health model which measured the consequences for diet-related illnesses.

In one scenario, we made all subsidy payments to farms conditional on them producing healthy and sustainable foods. Farmers would still be free to grow other crops and foods, just not with the support of subsidies.

We found that fruit and vegetable production would go up substantially – by about 20 per cent in developed countries. This would translate into people eating half a portion of fruit and vegetables more per day.

At the same time, meat and dairy production would go down by 2 per cent – shaving off 2 per cent from agricultural greenhouse gas emissions.

However, we also found that the economy could suffer if all subsidies were used in this way, drawing in workers to farming from more productive parts of the economy.

Fortunately, there are ways to avoid this.

Either make half of all subsidies conditional on growing healthy and sustainable foods, or combine these conditional subsidies with a reduction in the overall amount of payments – tying them, for example, to an amount informed by a country’s gross domestic product or population.

Related:

Each of those options would result in a healthier food supply and less greenhouse gas emissions without reducing economic output.

Policymakers in the European Union are currently aiming to reduce the environmental impacts of subsidy payments while those in the United Kingdom are considering a public money for public goods approach, which pays farmers to provide things like clean water, wildlife habitat and a nutritious food supply.

Sadly, proposals of this kind are often watered down when they’re implemented.

Our analysis proposes something which is largely missing from current plans: Changing the mix of food production. What food farms choose to grow has a greater effect on the environment and health than how it is grown.

Directing subsidies towards the production of healthy and sustainable food should be an essential part of reforming agriculture worldwide.

Marco Springmann is a Senior Researcher at the Oxford Martin Programme on the Future of Food, University of Oxford. This commentary first appeared on The Conversation.