Commentary: Rather than taxing tourists, countries should think about marketing lesser-known destinations

Taxes could help cities keep up with increasing tourist loads, but they lack the bite to curtail tourist volumes, says travel writer Ng Yixin.

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

SINGAPORE: “No touching Geisha” signs may look like they belong on a novelty T-shirt or gag gift. However, they highlight a real and growing problem in Gion, Kyoto.

With overzealous tourists flocking to the home of the geisha, the courtly, kimono-clad entertainers’ routine journey to work hardly goes undisturbed. Kyoto in 2019 cracked down on “geisha paparazzi” by banning photography in shidou (private roads) - before doubling down by restricting access to some of these alleys in March this year.

The problem of "tourism pollution" has returned with renewed urgency in Kyoto after the pandemic, where locals have seen their daily lives disrupted. Office workers have had to set aside extra time for their daily work commute due to being unable to board buses filled to capacity by tourists.

INEFFECTIVE BARRIERS TO TOURISM

Gion is one of several popular tourist districts in Japan that have erected barriers to keep out foreign visitors. There is also the recent viral example of a convenience store staving off tourists by putting up a screen to obscure a view of Mount Fuji.

Some believe that other barriers are springing up in the form of tourism taxes. In Japan, tourists now pay a small fee to enter Miyajima, home to the famed orange torii gate in Itsukushima Shrine.

Visitors to the ski resort town of Niseko, Hokkaido, will be charged a tiered accommodation tax starting November, paying up to 2,000 yen (US$12) per night. On top of that, Hokkaido plans to charge “lodging” taxes.

However, taxes are not the remedy for overtourism. Taxes could help attractions keep up with increasing tourist loads, by generating revenue needed to beef up visitor infrastructure for example. But they lack the bite to curtail tourist volumes.

Barely a month after the screen near Mount Fuji was put up, eager tourists have already torn holes into it to claim their prized view of Japan’s tallest peak. In a similar way, nominal taxes are not going to deter overzealous tourists. Travellers who have spent hours dreaming of Japan, and thousands of dollars on their vacation, would hardly bat an eyelid at a US$10 tax.

HIGHER TAX, HIGHER BARRIER?

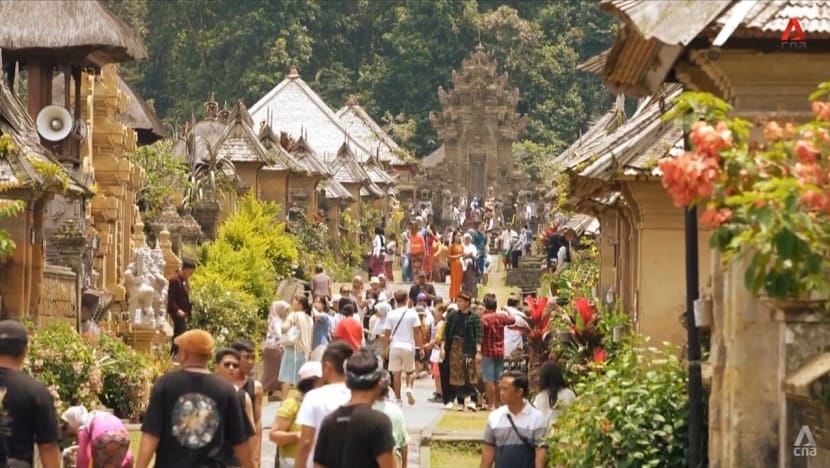

Meanwhile, Bali seems to believe that steep taxes can weed out bad behaviour by attracting only “quality” visitors. After imposing a 150,000 rupiah (US$9) tax earlier this year, Bali this month announced that it may raise taxes to around US$50, with plans to use revenue to step up on policing.

Supposing the upside of suppressing visitor volumes applies, steep tourism taxes are still far from ideal. Industry players believe that the increase would make nearby islands in Thailand more attractive to tourists. This would have an impact on local businesses that rely on in-destination visitor expenditure.

The big question is how government revenues can trickle down to the people. And the answer is probably not tighter policing of visitors, nor price deterrents. After numerous examples of tourists behaving badly, it should be evident that spending power and poor cultural awareness are not mutually exclusive.

If Bali wishes to encourage good behaviour from visitors, then perhaps more could be done in the areas of campaigning and education. Tax revenue could also fuel longer-term plans to develop or promote other parts of Bali beyond the usual suspects - from Seminyak, Kuta and Ubud to emerging spots like Amed, Mengwi and Klungkung.

THOUGHTFUL PLANNING AND MARKETING NEEDED

Taking a step back, it is worth noting that Kyoto and indeed many other parts of Japan have a strong culture of decorum and hospitality. This explains both the outrage with unencumbered tourist behaviour, but also the dilemma around deterring tourism.

Beyond imposing bans, fines and taxes, more needs to be done to entice them to lesser-known parts.

Indeed, drawing visitors away from overcrowded sites by marketing less popular destinations or seasons is a sensible way to combat overtourism. Countries as a whole are hardly at breaking point when it comes to sheer capacity. Many other lesser-known attractions wait in the wings for their time in the tourism spotlight.

The importance of dispersing visitors to places with lower footfall highlights yet another shortcoming of local tourist taxes. Travel dispersal is best undertaken on a broader level. Local players are not best placed to spend marketing dollars promoting other regions.

For instance, if Kyoto were to use tax revenues to prop up the city’s lesser-known attractions, tourists would still be unlikely to ditch the “must-sees” such as geisha hometown Gion, effectively multiplying “tourism pollution” in new areas.

If revenue from local taxes were to go anywhere other than infrastructure development, maybe it is cultural education. With the advent of short-form content, content creators are spreading awareness about a country’s customs to audiences abroad.

Traveller etiquette in Japan is a hot topic on TikTok, with clips on what not to do attracting millions of views. Street interviews, where locals share their sentiments about foreign visitors, are another popular format.

Perhaps some day now or in the near future, rather than “No touching geisha” signs, tourists would be discussing the “Top 3 things NOT to do in Kyoto” video they just saw on TikTok.

Ng Yixin is a Singapore-based independent writer for travel, sustainability and enterprise.